Rep:ASP8589

Abstract

The thermodynamic properties of magnesium oxide (binding energy, Helmoltz free energy, vibrational density of states and thermal expansion coefficient) were computationally investigated using two models: quasi-harmonic approximation (QHA) and molecular dynamics (MD). The behaviour of both models was explored at a range of temperatures, the melting point of MgO was observed using the MD model, and the effect of varying lattice size within MD simulations was investigated.

Introduction

Magnesium oxide, a crystal with the cubic (halite) structure, has a number of applications, including serving as a refractory material in construction (within kilns and crucibles), and as an insulator in heat-resistant electrical cables.1 MgO's stability at high temperatures is critical within these roles; rigorous analysis of its properties at high temperatures and pressures is therefore essential for preventing structural collapse or risk of fire.

Whilst studying existing materials under different conditions is essential in the understanding and design of novel materials, it is not always possible or practical to do this in a physical capacity. Analysis of compounds at temperatures and pressures far exceeding standard conditions is typically achieved using diamond-anvil cells (for example, investigations into the melting point of tantalum in a Laser-Heated Diamond Anvil Cell by Dewaele et al.).2 Such experiments are often prohibitively expensive. An alternative, as described below, involves computational analysis of compounds of interest.

Computational analysis of materials requires a suitable behavioural model to be chosen. The methods used were the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QHA) and Molecular Dynamics (MD).

Methodology

All calculations and simulations using both the QHA and MD models were performed using the General Utility Lattice Program (GULP), with visualisation provided by DL Visualise.

MgO Lattice Energy

The potential energy (U(r)) of each pair of ions was modelled using the Coulomb-Buckingham potential;

Where is the interionic distance, and are the ionic charges (+2 and -2 for Mg and O, respectively), and is the permittivity of free space. The first term represents the repulsion between ions due to electron cloud repulsion, the second caused by van der Waals interactions and the third is the electrostatic interaction. The constants A, B and C are provided by experimental results, and so describe realistic interactions between ions within a given structure (Table 1).

| Ion Pair | A | B | C | Cutoff Distance (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg-O | 0.130E+04 | 0.300 | 0.00 | 12.00 |

| O-O | 0.228E+05 | 0.149 | 27.9 | 12.00 |

The cutoff distance describes the maximum values at which the short range attractive and repulsive energies need be calculated; at higher separations, only the Coulomb electrostatic interactions are significant enough to be included. The total potential energy across all pairs of ions provides the lattice binding energy.

Phonon Density of States

The term 'phonon' is used to describe coupled vibrational motion of a series of atoms within a crystal lattice.

The relationship between the vibrational frequency () and wave vector () is known as the dispersion relation. For a system featuring only two types of ion (of masses and ), separated by distance , with force constant , the dispersion relation is as follows:3

In the case where equals zero, () can be either zero (in the case of subtraction of the second term) or at a maximum (in the case of addition). These two cases define two possible 'bands'; the accoustic band for the former, and the optical band for the latter.

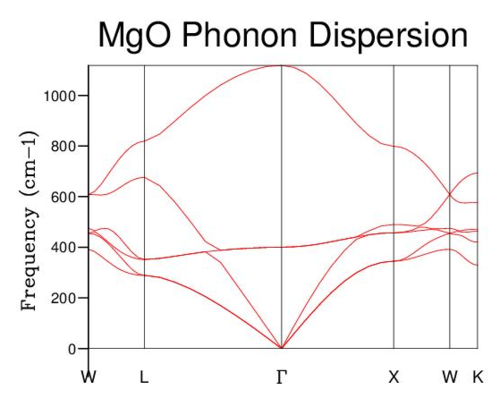

Systems with two different ions composing the primitive cell (as is the case for MgO) feature three accoustic branches and 3N-3 optical branches, where N is the number of ions in the unit cell. The phonons of accoustic branches involve both ions moving in the same direction. Optical branches describe phonons in which the two ions vibrate in opposite directions to one another (Fig. 1).

|

The phonon Density of States (DOS) is defined as the number of such vibrational states () per energy interval:

The DOS can therefore be extracted from the inverse gradient of the dispersion relation graph. Regions of the dispersion curve with smaller gradients therefore correspond to energies with high density of states. By varying the resolution of k-space within the GULP calculations (by dividing it into an increasingly fine grid), the DOS curve was shown to vary with the shrinking factor used. The shrinking factor was increased until the DOS curve converged to a constant shape.

The Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

Free Energy

One simple model relating the potential energy of an ion pair to their separation is the Harmonic Oscillator. Within this framework, the restorative force acting on an ion pair is directly proportional to their separation, generating a parabollic potential energy curve.

Where is the potential energy, is the force constant, and the equilibrium separation at which potential energy is at a minimum. This is derived from a Taylor-expansion of the potential energy around , defining the potential energy at the equilibrium separation as zero and identifying the first order differential as zero.

This model fails to account for deviation of the equilibrium bond length for excited states. Such a model cannot predict the behaviour of high energy systems, as it cannot allow for thermal expansion or bond breakage. For these reasons, the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation (QHA) is used as an improvement over the Simple Harmonic model by acknowledging that equilibrium bond length varies to minimise free energy () at a given temperature. Within the QHA model, free energy is calculated as:

Where is the internal lattice energy, is the angular frequency (), the first summation corresponds to zero point energies, and the second summation is the total thermal excitation energy. Including all possible states requires summing across all values within k-space (the k term of each summation), and across each band (the j terms).

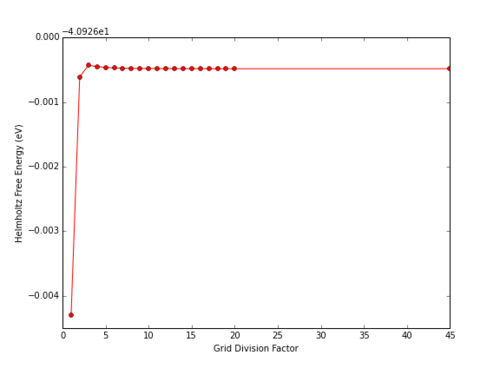

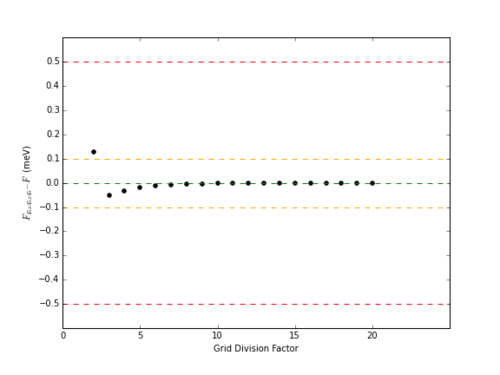

Because the free energy must be summed across all bands, the higher resolution the k-space grid, the greater the accuracy of the calculation. Calculations performed regarding density of states allowed a shrinking factor to be selected that is both high enough to provide a reasonable level of accuracy, and low enough so as not to be too computationally demanding. In this case, a temperature of 300 K was used during determination of Helmholtz free energy.

Thermal Expansion

Though the QHA model is incapable of accurately predicting crystal behaviour at high temperatures (approaching melting point), by allowing the crystal volume to change at higher temperatures, it can be used to calculate the thermal expansion coefficient and provide reasonable values for a range of low temperatures.

Molecular Dynamics

Thermal Expansion

An alternative system for determining the physical properties of a crystal involves Molecular Dynamics (MD). In order for the MD simulations to provide meaningful data, a larger crystal sample had to be simulated. A supercell consisting of 2x2x2 conventional cells containing 32 MgO units was generated and used to perform the simulation. Each ion is then assigned a velocity dependent on the temperature being tested, then the system is allowed to change over time as ions move and interact. By monitoring the properties of the system once it has reached equilibrium, the average cell volume can be determined for each temperature, and hence the thermal expansion coefficient can be calculated.

The algorithm used is a variant on the Velocity-Verlet algorithm; the following two relations are used to determine position () and velocity () for each ion at each timestep ():

The system used by GULP is a modification of Velocity-Verlet; velocity is determined for every half timestep interval. This is known as the Leap Frog algorithm:

Wherein () is the mass of the atom or ion. Again, a compromise must be made between accuracy and computational demands; the timestep used must be sufficiently large that a long enough timeframe can be simulated within a short period of time, but large enough that the simulation remains stable. If the timestep is too large, the positions of multiple atoms can become nearly overlapping after any given step. This causes them to strongly repel in the following step. As this can occur at any timestep, the total energy of the system can massively increase over time.

Results and Discussion

Lattice Binding Energy

By summing the potential energy from every ion pair as previously described, the lattice energy was calculated to be -41.07531759 eV (-3960 kJ/mol), showing similarity to the result obtained from physical analysis (3791 kJ/mol).4 The highly negative lattice energy is indicative of the strength of Mg-O bonding, due to the high charge-density ions. Such calculations are used to optimise the structure of compounds by determining the energetic minimum.

Phonon Dispersion Curve

The phonon dispersion curve was calculated by evaluating 50 points along the W-L-G-X-W-K path within k-space (Fig. 2). Six bands are clearly visible; three which possess a frequency of zero at the origin (the accoustic branches), and three which do not (the optical branches).

|

Phonon Density of States

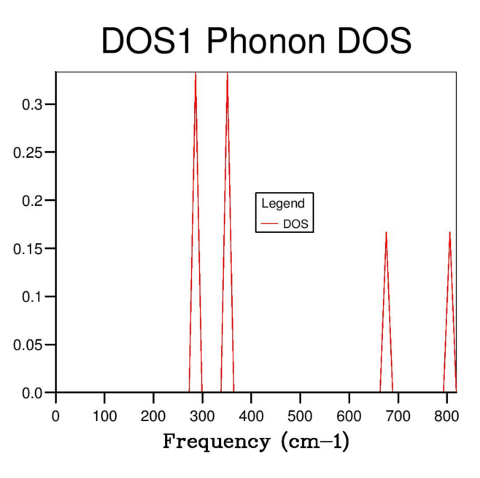

The DOS was determined for systems with different shrinking values, and hence different resolution k-space grids. With a shrinking factor of one (Fig. 3), only one k value is computed, and four sharp spikes are observed. Comparison of the frequencies of these peaks with the previously acquired phonon dispersion curve (Fig. 2) showed that this system corresponds to the symmetry point L.

By increasing the resolution and sampling the k-space using a finer grid, more k values were sampled, hence resulting in a more accurate DOS curve. The total area under the curve (the total number of states) must remain constant (as the number of states present is independent of how precisely they are measured), and the number of states associated with each frequency can be described more accurately.

|

|

Though theoretically an infinitely large shrinking factor is required to perfectly determine DOS for each frequency, this cannot be achieved in practise due to computational limitations. However, the DOS curve quickly converges to an extent suitable for practical applications. A grid resolution of 50x50x50 was selected (Fig. 4), as further increasing resolution did not visibly affect the DOS curve, and the calculations were not too computationally demanding. If time or processing power are more limited, a lower resolution can be used to achieve similar results.

Analysis of Other Crystals

When determining the resolution required to accurately model other crystals, their lattice size must be taken into consideration. Crystals exhibiting a larger Wigner-Seitz cell will have a smaller first Brillouin Zone, and vice versa. The Wigner-Seitz cell of CaO has similar dimensions to that of MgO, and so the DOS for CaO can be reliably calculated using the same resolution within k-space. As Faujasite possesses a larger unit cell, it has a smaller reciprocal lattice, and will require a lower resolution k-space grid to achieve a sufficiently accurate result for DOS calculations.

As described by the dispersion relation (above), the gradient of frequency () against wave vector () is larger for systems with larger force constants (). Steeper curves require a greater resolution in order to accurately differentiate between () values. The stronger the interaction between pairs of ions, the greater the force constant, and the steeper the curve (and hence the greater the resolution required for calculations). Ionic systems such as those within crystals of MgO, CaO and Faujasite have strong interactions between cations and anions. Metallic systems have weaker interaction between atoms, as they are screened by delocalised electrons. This factor decreases the resolution required to model metallic systems.

Metallic systems with a small Wigner-Seitz cell therefore have two competing factors; a large Brillouin Zone necessitates a high resolution k-space grid, and weak atomic interactions allow a low resolution system to be used as adjacent k values are likely to possess similar frequencies.

Free Energy

Similar to the determination of DOS, increasing the grid resolution increased the accuracy of the free energy calculation. Whereas DOS converged with a grid resolution of approximately 40x40x40, free energy converged to the 6 d.p. limit provided by the GULP display within a resolution of 18x18x18 (Table 2)

|

|

| Grid Resolution | Helmholtz Free Energy () /eV | () /meV |

|---|---|---|

| -40.930301 | 3.818 | |

| -40.926609 | 0.126 | |

| -40.926432 | -0.051 | |

| -40.926450 | -0.033 | |

| -40.926463 | -0.020 | |

| -40.926471 | -0.012 | |

| -40.926475 | -0.008 | |

| -40.926478 | -0.005 | |

| -40.926479 | -0.004 | |

| -40.926480 | -0.003 | |

| -40.926481 | -0.002 | |

| -40.926481 | -0.002 | |

| -40.926482 | -0.001 | |

| -40.926482 | -0.001 | |

| -40.926482 | -0.001 | |

| -40.926482 | -0.001 | |

| -40.926482 | -0.001 | |

| -40.926483 | 0.000 | |

| -40.926483 | 0.000 |

To achieve an accuracy of 1 meV or 0.5 meV, a grid size of 2x2x2 is required. To achieve an accuracy of 0.1 meV, 3x3x3 is required, and so on.

Thermal Expansion

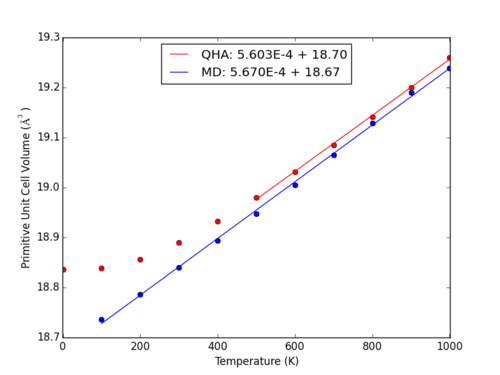

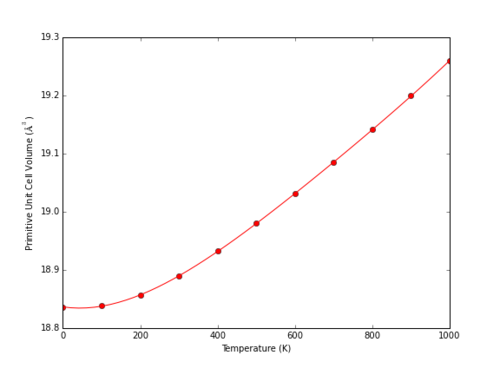

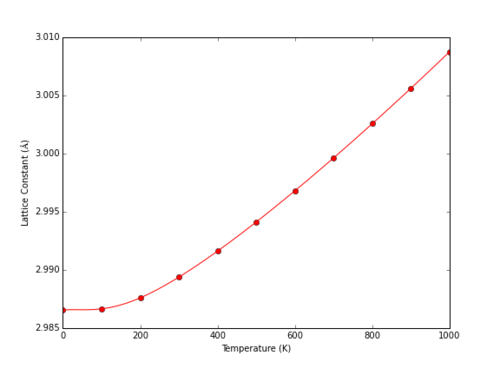

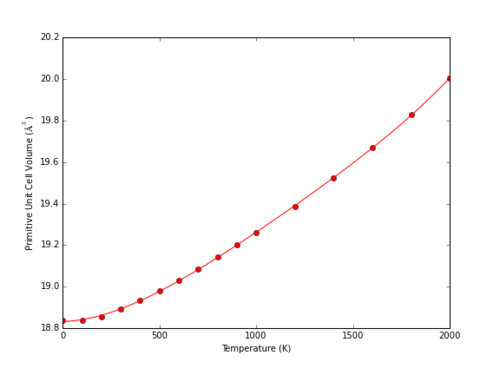

Quasi-Harmonic Approximation

The behaviour of MgO at a range of different temperatures at 0 Pa was determined within the QHA model. The Helmholtz free energy decreases with temperature as described within the description of the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation above: the only temperature dependant term as .

|

|

The cell volume does not increase significantly upon heating at lower temperatures. A simple harmonic oscillator model cannot predict thermal expansion, as the equilibrium bond length remains constant. Low temperature systems with energetic states close to the potential minimum can be approximated as harmonic, and hence will not demonstrate significant thermal expansion as the equilibrium bond length remains almost constant. The predicted primitive cell volume can be described as varying as a fourth order polynomial.

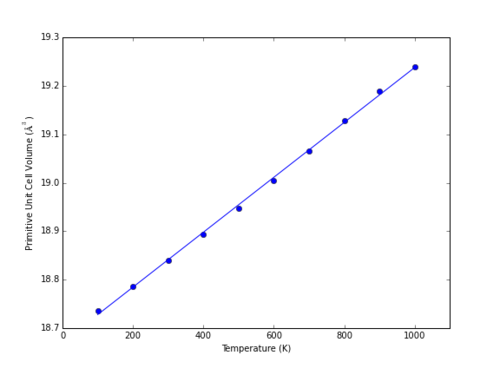

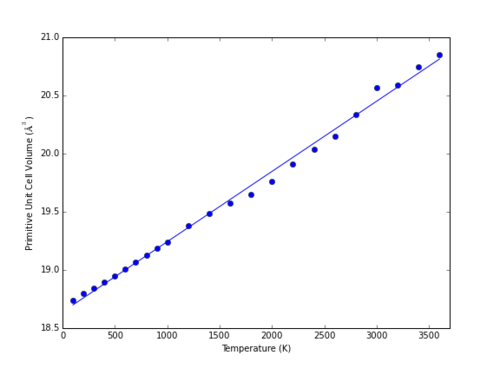

Molecular Dynamics

As previously described, the thermal expansion of MgO was simulated within the MD framework by allowing the system to reach equilibrium at a range of temperatures, and identifying how equilibrium primitive cell volume varies with temperature. The low temperature limit still demonstrates linearity between cell volume and temperature (Fig. 10).

|

This is due to the classical nature of the MD calculations, rather than the quantum-mechanic basis of the QHA model. Within quantum mechanics, the zero-point energy is dependent upon the vibrational frequencies of the system, and is greater than zero. The classical mechanics model used has no such equivalent, and energy of can fall to zero with temperature, resulting in uniformly linear behaviour. Some fluctuation is observed, which can be minimised with smaller timesteps, a larger system, and by ensuring equilibrium has been reached prior to taking measurements. However, this is computationally expensive, and so a compromise is reached between time required and accuracy of results achieved.

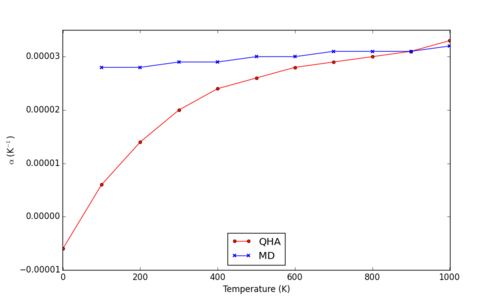

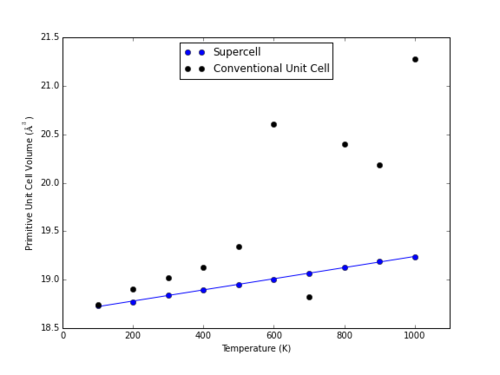

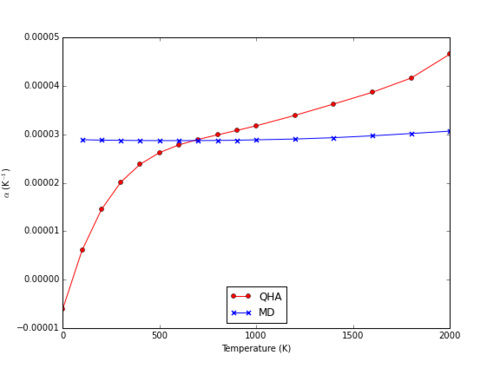

Comparison

At higher temperatures, the QHA and MD results for thermal expansion coefficient converge to similar values, for example at the intersection at 900 K (Fig. 12):

Within the range of 500-1000 K, both methods demonstrate a moderately linear relationship between cell volume and temperature (Fig. 11). At higher temperatures, the QHA model fails to account for bond breaking, and approaching these temperatures the MD method is more accurate. Both of these methods overestimate the heat capacity as compared to physical analysis; in order to achieve a more accurate estimate within molecular dynamics, a larger cell must be used to better mimic the near infinite lattice of a real crystal. As shown in Fig. 13, use of a smaller cell (in this case, a 1x1x1 conventional unit cell) for MD simulations generates extreme fluctuations.

|

At higher temperatures, the volume predicted by the QHA model continues to increase with the fourth power of temperature (Fig 14). The MD model however begins to deviate from linearity, with a marked increase in volume at approximately 3000 K (Fig. 15). This corresponds to the melting point of MgO; literature examples of MD simulations of MgO describe similar behaviour indicative of a melting point at 2990 ± 100 K.5

|

|

At higher temperatures, the expansion coefficient values predicted by the QHA model deviate significantly from those of MD, which remain moderately linear. MD predicts an expansion coefficient almost independent of temperature, whereas QHA predicts a far greater range of values between 0 and 2000 K (Fig. 16).

|

In comparison to observed heat capacities, the values predicted by simulations show similarity to that calculated from physical experimentation, particularly that of the MD method at temperatures between 400 and 1000 K (approximately 3.1*10-5).6,7 The main causes of deviation from physical results comes from interactions between ions not accounted for in this model. For example, covalent contributions to bonding are not predicted by the Coulomb-Buckingham model, and so do not contribute toward stabilisation of the crystal structure, and do not accordingly lower the thermal expansion coefficient.

Conclusion

The properties of magnesium oxide were explored computationally through use of both quasi-harmonic approximations and molecular dynamics. The vibrational density of states was shown to converge with increasingly high resolution k-space sampling, allowing an optimal shrinking factor to be selected for QHA modeling. Free energy was determined, and the thermal expansion coefficient explored at a range of temperatures allowing the observation of anomalous behaviour for each model under different temperature ranges.

Further experimentation would involve generation of a larger supercell for the purposes of MD analysis, and comparison of the results obtained to that using the current supercell. More accurate results could also be obtained through use of a longer equilibration step and smaller timestep value, and simulations could be performed on other ionic and metallic systems in order to determine the effectiveness of the interaction models for systems with different properties.

References

1. M. A. Shand and John Wiley & Sons., The chemistry and technology of magnesia, Wiley-Interscience, 2006.

2. A. Dewaele, M. Mezouar, N. Guignot and P. Loubeyre, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2010, 104, 255701.

3. P. K. Misra, Physics of condensed matter, Academic Press, 2012.

4. D. L. Reger, S. R. Goode and D. W. (David W. Ball, Chemistry : principles and practice., Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning, 2010, 330.

5. L. Vočadlo and G. D. Price, Phys. Chem. Miner., 1996, 23, 42–49.

6. Y. Fei, American Geophysical Union, 1995, pp. 29–44.

7. E. A. Perez‐Albuerne and H. G. Drickamer, J. Chem. Phys., 1965, 43, 1381–1387.