Molecular Reaction Dynamics (st4215)

In this computational lab, the reactivity of triatomic systems - where a single atom and a diatomic molecule collide - is studied. This is done by calculating Molecular Dynamics trajectories using a MATLAB software.

Exercise 1: H + H2 system

The first exercise involves a triatomic system with the atom H3 colliding with the diatomic molecule H1-H2. The initial input values used to calculate the trajectories of the atoms are shown below:

| Initial distance between atoms | Initial momentum | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 and H2 | r1(0) = rBC(0) = 0.74 | p1(0) = pBC(0) = 0 |

| H2 and H3 | r2(0) = rAB(0) = 2.30 | p2(0) = pAB(0) = -2.7 |

The transition state

Any molecular trajectory proceeds via a transition state, which is defined as the maximum on the minimum potential energy path linking reactants and the products. Hence in determining whether a molecular trajectory is reactive, the position of the transition state is first determined - a reactive trajectory will pass through the transition state and move towards the formation of the products.

Dynamics of the transition state

A potential energy surface is generated from a trajectory calculation. We can identify the approximate position of the transition state by locating the maximum on this surface.

What value does the total gradient of the potential energy surface have at a minimum and at a transition structure? Briefly explain how minima and transition structures can be distinguished using the curvature of the potential energy surface.

At both a minimum and at a transition structure in the potential energy surface, the total gradient is 0. However, as the transition state corresponds to a maximum on the potential energy surface, it can be distinguished from the various minima by the second derivative. At a maximum where the transition state is located, the second derivative will be negative, while at the minima, the second derivative will be positive.

Locating the transition state

The transition state can be located by setting r1 = r2 , since the H + H2 surface is symmetric, and p1 = p2 = 0.0. The latter condition is because by starting a trajectory on the ridge, with no gradient in the direction at right angles to the ridge, the trajectory will remain oscillating on the ridge and never fall off, enabling us to locate the TS geometry.

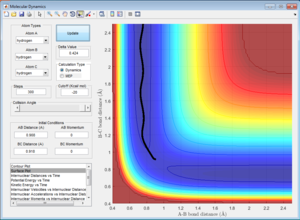

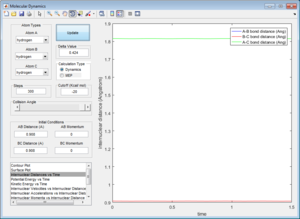

Report your best estimate of the transition state position (rts) and explain your reasoning illustrating it with a “Internuclear Distances vs Time” screenshot for a relevant trajectory.

The transition state position is achieved when the r1 = r2 = rts = 0.908. This is evident from the graph below where it can be seen that internuclear distance does not vary with time when rts = 0.908. This means that the transition state has been achieved as distance between atoms are no longer changing.

Trajectories from the transition state

If a trajectory is started at the transition state but is not given an initial momentum, it will not move. However, by displacing the positions slightly from the transition state with zero initial momenta, the reactants may "roll" towards the products and we can find the resulting trajectory.

To do this, the following initial conditions were set:

| Initial distance between atoms | Initial momentum | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 and H2 | r1 = rBC = rts+0.01 = 0.918 | p1 = pBC = 0 |

| H2 and H3 | r2 = rAB = rts = 0.908 | p2 = pAB = 0 |

Calculating the reaction path

The reaction path (or minimum energy path, mep) is a special trajectory that corresponds to infinitely slow motion (i.e. the velocity always reset to zero in each time step).

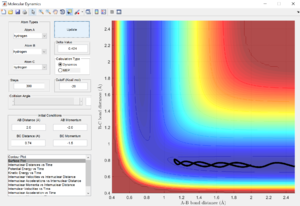

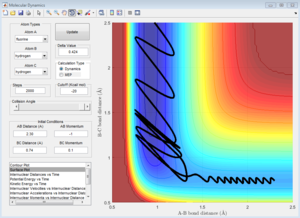

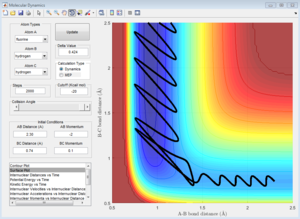

Comment on how the mep and the trajectory you just calculated differ.

Calculation via the minimum energy path shows a trajectory which follows the valley floor directly in a straight line to H1 + H2-H3. However, the trajectory generated from a dynamics calculation is a wavy line instead, as the diatomic molecule is vibrating. This is because the mep calculation type calculates the minimum vibrational energy state of the molecule at each point in the reaction, and hence shows a straight line, whereas the dynamics calculation takes into account vibrations and oscillations between different vibrational energy levels, hence the line is wavy.

(Fv611 (talk) 16:02, 24 May 2017 (BST) Yes, but why is the mep straight and the dynamic-generated line wavy? Hint: it has to do with how both methods treat velocity.) Using the graph of internuclear distance against time as well as internuclear momenta against time, we can determine the final values of positions r1(t) and r2(t) as well as the average momenta p1(t) and p2(t) at large values of t.

-

Final distance between atoms Final momentum x value y value x value y value t = 1.495 r1(t) = rBC(t) = 5.281 t = 1.495 p1(t) = pBC(t) = 2.481 t = 1.495 r2(t) = rAB(t) = 0.7453 t = 1.495 p2(t) = pAB(t) = 1.555

Reactive and unreactive trajectories

From the previous calculations, it can be concluded that trajectories with initial conditions in the range r1 = 0.74, r2 = 2.0, with -1.5 < p1 < -0.8 and p2 = -2.5 are reactive. Although it seems reasonable to assume that all trajectories starting with the same positions but higher values of momenta would be reactive, since they have enough kinetic energy to overcome the activation barrier, this is not necessarily true. This can be illustrated in the following examples.

Using the initial atom positions r1 = 0.74 and r2 = 2.0, trajectories were run with the following momenta combinations:

| p1 | p2 | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory 1 | -1.25 | -2.5 | Reactive |

| Trajectory 2 | -1.5 | -2.0 | Unreactive |

| Trajectory 3 | -1.5 | -2.5 | Reactive |

| Trajectory 4 | -2.5 | -5.0 | Unreactive |

| Trajectory 5 | -2.5 | -5.2 | Reactive |

Complete the table by adding a column reporting if the trajectory is reactive or unreactive. For each set of initial conditions, provide a screenshot of the trajectory and a small description for what happens along the trajectory.

Transition state theory

From the examples above, we can see that trajectories starting from the correct initial positions but with higher values of momenta are not necessarily reactive. However, such cases of unreactivity are not accounted for by the transition state theory. The transition state theory (TST) enables us to quantify the rate of a reaction if the estimated properties of the transition state are known.[1] However, it is based on several limitations, and hence reaction rates determined theoretically by TST may deviate from experimentally determined values.

State what are the main assumptions of Transition State Theory. Given the results you have obtained, how will Transition State Theory predictions for reaction rate values compare with experimental values?

One of the limitations of the TST is that it assumes that atomic nuclei behave according to classical mechanics.[2] Hence it makes the assumption that as long as atomic nuclei collide with sufficient energy to form the transition structure, the reaction will proceed and the products will be formed. This means that atomic nuclei colliding with insufficient energy do not react, and those colliding with more than enough energy are able to react. However, from the examples discussed above, we know that this is not true, as unreactive trajectories can also result even with higher values of momenta (and hence kinetic energy). In general, rates calculated using the TST are lower than experimentally determined values, as it does not account for reactive trajectories whereby atomic nuclei do not have enough energy to overcome the activation barrier. Such nuclei may still be able to react via quantum tunnelling through the barrier.[3] This is especially predominant in reactions with low activation energy barriers.

Another assumption that the TST makes is that the reaction system will always pass over the lowest energy saddle point on the potential energy surface, which corresponds to the transition state. However, this is not necessarily the case. Especially at higher temperatures, molecules may populate higher energy vibrational levels. Collisions may therefore lead to transition states which are not necessarily at the lowest energy saddle point.[4] Hence as the TST does not account for these possibilities, the calculated rate will be lower than experimentally determined values.

(Fv611 (talk) 16:02, 24 May 2017 (BST) Good discussion, but how does TST describe recrossing?)

Exercise 2: F - H - H system

In this exercise, the F-H-H triatomic system is studied whereby the atom F collides with the diatomic molecule H1-H2.

Inspection of the potential energy surface

Reaction energetics

Classify the F + H2 and H + HF reactions according to their energetics (endothermic or exothermic). How does this relate to the bond strength of the chemical species involved?

The F + H2 → H + HF reaction is exothermic, while the reverse reaction (H + HF → F + H2) is endothermic.[5] This indicates that the H-F bond strength is greater than the H-H bond strength.

Locating the transition state

Locate the approximate position of the transition state.

The transition state was determined by a similar method as in Exercise 1. The initial conditions below gave the position of the transition state:

| Initial distance between atoms | Initial momentum | |

|---|---|---|

| F and H1 | rAB = rFH = 1.81 | pAB = pFH = 0 |

| H1 and H2 | rBC = rHH = 0.74 | pBC = pHH = 0 |

As explained above, setting the initial momenta as 0 for both enables us to locate the position of the transition state by constraining it to a point on the ridge. rBC = rHH was set at 0.74 as this is the H-H bond distance in H2. Varying rAB = rFH by trial and error allowed us to determine its value at 1.81. This was guided by Hammond's Postulate, which states that in an exothermic reaction like this one, the transition state will be closer to the reactants. Hence rAB = rFH should be higher than rBC = rHH.

This can be confirmed by the potential energy surface plot (using an mep calculation) as well as the graph of internuclear distance against time. Both show that when rAB = rFH = 1.81, the molecule is not moving, oscillating or vibrating, indicating that it has attained the transition state position.

Activation energy

Once the position of the transition state has been determined, the activation energies for the forward and reverse reactions can be calculating by slightly displacing the atoms from the transition state position - the saddle point on the potential energy surface. Depending on where the initial position is relative to the transition state, the atoms will naturally roll down (without any initial momentum) towards either the reactants (F + H2) or the products (H + HF). Displacing the atoms from the transition state position is necessary as starting the trajectory at the transition state (with no initial momentum) would mean that the atoms will remain there forever.

Report the activation energy for both reactions.

It was previously determined that the transition state was attained when rAB = rFH = 1.81 and rBC = rHH = 0.74. Hence the following conditions were used to determine the respective activation energies:

| rAB = rFH | rBC = rHH | |

|---|---|---|

| F + H2 → H + HF (forward reaction) | 1.82 | 0.74 |

| H + HF → F + H2 (reverse reaction) | 1.80 | 0.74 |

with no initial momentum being given (pFH = pHH = 0) for both cases.

Activation energies can then be determined by looking at the drop in potential energy as the reactants move towards the products.

| Initial (reactants) | Final (products) | Activation energy / kcal mol-1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F + H2 → H + HF (forward reaction) | x = 0.085 y = -103.8 |

x = 400 y = -103.9 |

-103.8 - (-103.9) = 0.1 |

| H + HF → F + H2 (reverse reaction) | x = 73.66 y = -103.8 |

x = 98.46 y = -133.6 |

-103.8 - (-133.6) = 29.8 |

It can be seen that potential energy for the forward reaction does not taper off to a constant value despite the large number of steps used in the calculation; this is likely due to the very small activation energy for the reaction and hence the value calculated may be limited in accuracy.

(Fv611 (talk) 16:02, 24 May 2017 (BST) Good, well done on pointing out that the mep doesn't converge.)

Reaction dynamics

Reaction energy

Identify a set of initial conditions that results in a reactive trajectory for the F + H2, and look at the “Animation” and “Internuclear Momenta vs Time”. In light of the fact that energy is conserved, discuss the mechanism of release of the reaction energy. How could this be confirmed experimentally?

By trial and error, the initial conditions below were determined to give a reactive trajectory for F + H2 → H + HF:

| Initial distance between atoms | Initial momentum | |

|---|---|---|

| F and H1 | rAB = rFH = 2.30 | pAB = pFH = -2.7 |

| H1 and H2 | rBC = rHH = 0.74 | pBC = pHH = 0 |

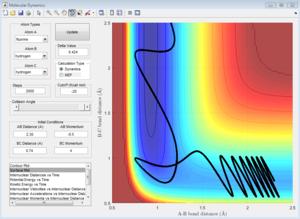

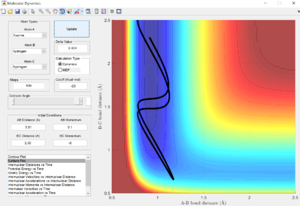

The resulting potential energy surface plot confirms that the forward reaction F + H2 → H + HF is exothermic as the products are lower in energy that the reactants.

We can confirm this experimentally by calorimetry - knowing the energy difference between reactants and products allows us to calculate the amount of heat released and hence the corresponding increase in temperature. Measuring this increase in temperature allows us to confirm that that this exothermic reaction has indeed occurred.

From the potential energy surface plot, we can also see that most of the energy input into the system is converted into vibrational energy. This is evident as the atoms do not move in a straight translational motion but in a wavy motion. As A-B (F-H1) bond distance decreases, corresponding to conversion to translational energy, it can be seen that B-C (H1-H2) bond distance is oscillating, indicating that energy is also converted to vibrational energy. Similarly, after the activation barrier is crossed, A-B (F-H1) bond distance oscillates greatly as B-C (H1-H2) bond distance increases, indicating that most of the energy input is converted to vibrational energy (oscillation) rather than translational energy (decreasing of B-C bond distance).

We can confirm this experimentally by IR spectroscopy. As can be seen in the graph of internuclear momenta against time, the frequency and amplitude of vibrations change over time as reactants move to products. Comparing the IR spectrum of the reactants and products firstly allows us to confirm that the energy is vibrational in nature - large peaks should be seen on the IR spectrum. Differences in frequency of vibration also allows us to distinguish between products and reactants and that the reaction has indeed taken place.

Investigating Polanyi's empirical rules

Discuss how the distribution of energy between different modes (translation and vibration) affect the efficiency of the reaction, and how this is influenced by the position of the transition state.

Polanyi's rules state that vibrational energy is more efficient in promoting a reaction with late transition states, while translational energy is more efficient in promoting reactions with early transition states.[6] This can be illustrated in the trajectories discussed below.

Calculation 1: F + H2 → H + HF

A calculation with the following initial conditions was set up, varying the value of pHH in the range -3 to 3 to investigate the effect on the resulting trajectories.

| Initial distance between atoms | Initial momentum | |

|---|---|---|

| F and H1 | rAB = rFH = 2.30 | pAB = pFH = -0.5 |

| H1 and H2 | rBC = rHH = 0.74 | -3 ≤ pBC = pHH ≤ 3 |

It was found that all trajectories with these values of pHH were unreactive due to various reasons.

| Magnitude of pHH | Screenshot | Description |

|---|---|---|

| |pHH| = 0 | When pHH = 0, meaning that no initial momentum is given to H-H, the atoms do not have enough energy to cross the activation barrier, and their motion stops abruptly before even reaching near the transition state position. | |

| |pHH| = 1 | Increasing the magnitude of pHH to 1 increases the amount of vibrational energy given to the reactants. However, in both cases, it can be seen that the atoms still do not have enough energy to cross the activation barrier. | |

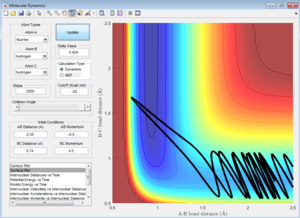

| |pHH| = 2 | When pHH = -2, atoms do not have enough energy to cross the activation barrier and return to the reactants. When pHH = 2, the atoms have enough energy to cross the activation barrier, however they bounce back, resulting in an unreactive trajectory. | |

| |pHH| = 3 | Increasing the magnitude of pHH to 3, meaning an increase in the vibrational energy given to the reactants, give the atoms enough energy to cross the activation barrier. However, the trajectory is still unreactive as the atoms bounce back after crossing the barrier. |

This is an expected result, as the forward reaction F + H2 → H + HF is exothermic and therefore has an early transition state. Based on Polanyi's rules, translational energy plays a more important factor than vibrational energy in promoting the reaction. However, in the above cases, the molecule was given varying amounts of vibrational energy (pHH) which were often much greater than translational energy (pFH = -0.5). Hence, it is expected that these initial conditions would result in unreactive trajectories.

Increasing the magnitude of pHH to 4, however, gives an unexpected result - reactive trajectories are obtained. This is perhaps due to the very large amount of vibrational energy given to the molecules. However, this is likely an exception, as increasing the magnitude of pHH to 4.5 again gives unreactive trajectories with the atoms bouncing back after crossing the activation barrier.

Following Polyani's rules and giving the atoms more translational energy by increasing the momentum pFH = -0.8, and considerably reducing the momentum pHH = 0.1, gives reactive trajectories as expected. Further increasing pFH to -1 and -2 also result in similarly expected reactive trajectories.

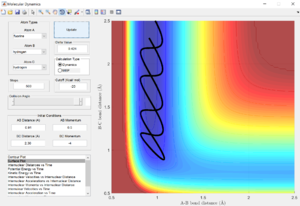

Calculation 2: H + HF → F + H2

Polanyi's rules are also exemplified in the reverse reaction, H + HF → F + H2. This reaction is endothermic and therefore has a late transition state. Hence, according to Polanyi's rules, vibrational energy should be more efficient in promoting this reaction.

Indeed, low values of vibrational energy (pFH) and high values of translational energy (pHH) give unreactive trajectories:

However, increasing vibrational energy (pFH) and reducing translational energy (pHH) allow us to obtain reactive trajectories:

Hence both calculations show that Polanyi's rules provide a good basis to determine whether the distribution of energies (between translational or vibrational modes) are efficient in promoting a certain reaction depending on whether it has a early or late transition state.

(Fv611 (talk) 16:02, 24 May 2017 (BST)Very good discussion + examples)

References

- ↑ R. J. Silbey, R. A. Alberty, M. G. Bawendi. Physical Chemistry, 4th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2005

- ↑ Eyring, H. (1935). "The Activated Complex in Chemical Reactions". J. Chem. Phys. 3 (2): 107–115.

- ↑ Masel, R. (1996). Principles of Adsorption and Reactions on Solid Surfaces. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Pineda, J. R.; Schwartz, S. D. (2006). "Protein dynamics and catalysis: The problems of transition state theory and the subtlety of dynamic control". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 361 (1472): 1433–1438.

- ↑ John C. Polanyi; Jerry L. Schreiber. The reaction of F + H2→ HF + H. A case study in reaction dynamics. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc., 1977, 62, 267-290.

- ↑ John C. Polanyi. Concepts in reaction dynamics. Acc. Chem. Res., 1972, 5 (5), pp 161–168.