Mod demo project

Mini Project

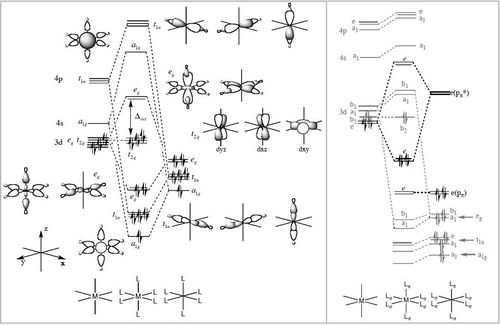

During first, second and third year lectures, a common picture which is shown is the bonding picture of metal carbonyl complexes (left) where the metal-carbonyl bond is built up of OC->M σ-donation and OC<-M π-backbonding. This bonding picture helps us understand what happens when the different components change in magnitude (for instance the back donation increases) and is known to be associated with the frequency of the carbonyl vibration.

From theory it has been suggested that with relatively less backbonding there will be a higher ν(CO), corresponding to a strong C-O bond, than for a complex with relatively more backbonding, corresponding to a strong M-C bond, as more electron density is between the M-C bond and less between the C-O bond.

This project will look at three metal carbonyl complexes from the first row of transition metals in the complexes: [Ti(CO)6]2-, [Cr(CO)6] and [Fe(CO)6]2+ by first creating optimisised structures and then using these for frequency and molecular orbital analysis.

Optimisation

For the complexes being studied in this project it was necessary to use pseudo-potentials for the metal. Therefore all input files were edited according. An example of the generic script used for the optimisation is (where M = Ti, Cr, Fe and n = -2, 0, +2 for the actual calculations carried out for this project):

# opt(maxcycle=50) b3lyp/gen geom=connectivity pseudo=cards gfinput [M(CO)6] Optimisation using pp and basis sets n 1 M -0.00000000 0.00000000 -0.00000000 C 0.00000000 0.00000000 1.90000000 C 0.00000000 1.90000000 0.00000000 C 1.90000000 0.00000000 -0.00000000 C -0.00000000 0.00000000 -1.90000000 C 0.00000000 -1.90000000 -0.00000000 C -1.90000000 0.00000000 0.00000000 O 0.00000000 0.00000000 3.01540000 O 0.00000000 3.01540000 0.00000000 O 3.01540000 0.00000000 -0.00000000 O 0.00000000 -3.01540000 -0.00000000 O -3.01540000 0.00000000 0.00000000 O -0.00000000 0.00000000 -3.01540000 1 2 1.0 3 1.0 4 1.0 5 1.0 6 1.0 7 1.0 2 8 3.0 3 9 3.0 4 10 3.0 5 13 3.0 6 11 3.0 7 12 3.0 8 9 10 11 12 13 M 0 LanL2DZ **** C O 0 6-31G(d,p) **** M 0 LanL2DZ

The combination of using gen as the 'basis set' input and the key words pseudo=cards gfinput in the top line with the lines added at the end of the input file direct the calculation to use the pseudo-potential lanl2dz on the metal and the moderate level basis set 6-31G on the carbon and oxygen atoms. Further, to aid the calculation, Ohsymmetry was imposed on all the complexes.

| Compound | Ti | Cr | Fe |

| File Type | .log | .log | .log |

| Calculation Type | FOPT | FOPT | FOPT |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | Gen | Gen | Gen |

| Charge | -2 | 0 | 2 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) / a.u. | -738.0860344 | -766.3677063 | -802.7495601 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.00002032 | 0.00006245 | 0.00015897 |

| Imaginary Freq | |||

| Dipole Moment / Debye | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Point Group | OH | OH | OH |

| Job cpu time | 0 days 0 hours 7 minutes 21.7 seconds | 0 days 0 hours 5 minutes 3.8 seconds | 0 days 0 hours 4 minutes 8.4 seconds |

| D-Space Link | DOI:10042/to-9658 | DOI:10042/to-9657 | DOI:10042/to-9659 |

From this data it can be seen that a minima was reached for each of these and that was confirmed by looking at the .log files for series of 'converged'. In addition, from looking at the .log files, it was possible to ensure that the symmetry was imposed on these compounds. However it is interesting to note that Gaussian cannot calculate Oh (at the level of calculations used for this project) and therefore uses D2h instead (see excerpt for the Cr complex below).

Stoichiometry C6CrO6 Framework group OH[O(Cr),3C4(OC.CO)] Deg. of freedom 2 Full point group OH NOp 48 Largest Abelian subgroup D2H NOp 8 Largest concise Abelian subgroup D2H NOp 8

These files were then used for the frequency and orbital analysis. Once frequency analysis had confirmed that minima were achieved during the optimisation, it was also possible to determine bond lengths for these complexes.

| Computational M - C / Å | Literature M - C / Å | Computational C - O / Å | Jmol | ||||

| Ti | 2.05 | 1.18 |

| ||||

| Cr | 1.92 | 1.15 |

| ||||

| Fe | 1.94 | 1.997[2] | 1.13 |

|

To determine the reliability of the C-O bond lengths these can be compared to the value for free C=O which is 1.21Α[3]. The value found for the Fe complex has an absolute difference of 0.06Α and the values for CO are all within reason when compared to the literature value.

Frequency Analysis

Using the optimised structures a frequency analysis could be carried out. From this it was possible to determine that minima were found for the three compounds as the energies were almost identical and no negative frequencies were obtained. The relevant parts of the summaries are shown below:

| Compound | Ti | Cr | Fe |

| Calculation Type | FREQ | FREQ | FREQ |

| Calculation Method | RB3LYP | RB3LYP | RB3LYP |

| Basis Set | Gen | Gen | Gen |

| Charge | -2 | 0 | 2 |

| Spin | Singlet | Singlet | Singlet |

| E(RB3LYP) / a.u. | -738.0860344 | -766.3677063 | -802.7495601 |

| RMS Gradient Norm / a.u. | 0.0000204 | 0.00006333 | 0.00015943 |

| D-Space Link | DOI:10042/to-9674 | DOI:10042/to-9672 | DOI:10042/to-9673 |

| IR Spectra |  |

|

|

In the table above an image of each of the IR spectra are included. For the Cr complex the vibrations associated with the peaks have been indicated. From these computational jobs it is possible to determine both M-C and C-O vibrations. In experimental work it is generally challenging to accurately determine the M-C frequencies as these occur in the fingerprint region. Therefore this type of analysis could be used to look further into the changes in the M-C frequencies. The frequencies have been summarized in the table below and literature values have been found for the C-O stretches:

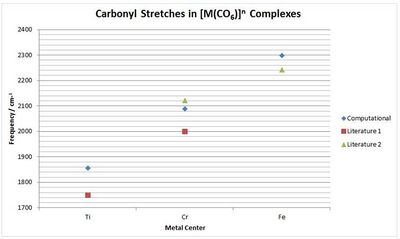

| Compound | Ti | Cr | Fe |

| Computational M-C / cm-1 | 450 | 430 | 339 |

| Computational M-C / cm-1 | 639 | 692 | 580 |

| Computational C-O / cm-1 | 1855 | 2086 | 2297 |

| Literature C-O[1] / cm-1 | 1750 | 2000 | n/a |

| Literature C-O[4]/ cm-1 | n/a | 2119 | 2241 |

To compare the graph right was constructed. This shows that there the calculated frequencies are reasonable and taking into account the 10% systematic error, correspond quite closely to literature values. Therefore it can be concluded that this method is successful in investigating the carbonyl stretch and this data does appear to support the suggestion that an increase in the π-back donation increases the C-O bond length and has a lower carbonyl frequency.

Orbital Analysis

Using the formatted checkpoint files the molecular orbitals were determined for these complexes. Before starting, the MO diagram for ML6 with all σ-donor ligands was thought to be a good place to start for interpreting the orbitals which resulted. However, looking at an MO diagram for just one π-donor ligand it is clear that the actual picture is significantly more complicated.

The large table below summarises the occupied MOs which were found along with interpretations. Along the left are screen captures of orbitals. To the right of each picture are between 1-6 descriptions of degenerate orbitals which correspond to the image (numbers link the exact picture with description).In addition tentative symmetry assignments have been made under some of the images. Due to the complexity of these MOs as well as Gaussian's use of D2h instead of Oh, it is not possible to fully assign the symmetry. It can be noted that an attempt was made to interpret the data under 'second order perturbation theory analysis of fock matrix in NBO basis' to determine the extent of mixing however this was again highly complicated due to the size of the system.

The energies of each of these levels can also be compared between the complexes:

| MOs | Energy [Ti(CO)6]2- | Energy [Cr(CO)6] | Energy [Fe(CO)6]2+ |

| 47-49 | 0.147 | -0.257 | -0.712 |

| 44-46 | -0.055 | -0.416 | -0.802 |

| 42-43 | -0.175 | -0.451 | -0.829 |

| 39-41 | -0.110 | -0.460 | -0.835 |

| 36-38 | -0.115 | -0.466 | -0.839 |

| 33-35 | -0.124 | -0.482 | -0.854 |

| 30-32 | -0.126 | -0.485 | -0.856 |

| 29 | -0.138 | -0.508 | -0.879 |

| 27-28 | -0.237 | -0.573 | -0.932 |

| 24-26 | -0.238 | -0.576 | -0.937 |

| 23 | -0.786 | -0.619 | -1.002 |

| 21-22 | -1.107 | -1.152 | -1.534 |

| 17-20 | -1.982 | -1.153 | -1.536 |

| 14-16 | -9.962 | -1.848 | -2.721 |

| 13 | -9.962 | -2.895 | -3.946 |

| 7-12 | -18.893 | -10.321 | -10.701 |

| 1-6 | -18.893 | -19.249 | -19.632 |

| D-Space Link | DOI:10042/to-9871 | DOI:10042/to-9870 | DOI:10042/to-9872 |

These energies are quite large, especially considering that a pseudo-potential was used. The overall pattern of these values follows that of the energy from the optimisation (-738, -766 and -802 a.u.) which is expected because these individual orbitals contribute to the total energy.

Conclusion

This project investigated a series of metal carbonyl complexes with a focus on the vibrational frequency of the carbonyl in IR spectroscopy. The use of this method to look at the degree of back bonding is widely used in research and it was found that this was also computationally possible. The structures were optimised to a reasonable degree with bond lengths comparable to literature. In addition, the results of the calculations for the carbonyl frequencies was closely matched to literature values which were found. This is especially true since these values vary slightly in literature (as seen by the two different sources) and also because there is a 10% systematic error associated with these calculations. In addition, the molecular orbitals were generated and these could also be described to a certain extent based on a simpler σ-donor diagram. As these are highly symmetric complexes, having Oh symmetry, there are few electronic properties which could be investigated. However this and many other properties could be considered by making small changes to the project, resulting in further research.

Further Study

Several ideas of the many ways computational analysis could be used to continue studying this area are outlined below:

- Look at further metals of the same row in order to get a more complete picture and verify that the trend continues as expected.

- Look at a series of metals going down one group and investigate how the properties change as the metal becomes larger and has more electrons.

- The bonding picture of metal carbonyl complexes used is one that is commonly described by the Dewar-Chatt-Duncanson (DCD) model where the π-back donation is the most important factor for binding energy. However recently it has been suggested that the HOMO-LUMO contributions from metal and CO fragments could also have a significant effect with a greater interaction energy between these fragments being correlated with an increase in the stability. As the MOs can be clearly observed using these computational methods, it would be extremely interesting to look into this new suggestion and investigate how the HOMO-LUMO contributions affect the (bond) energy of metal carbonyl complexes and the determination of which bonding component is more important. This could be done by comparing fragments with high lying HOMO, implying that backbonding is the dominant component versus fragments with low lying LUMOs where σ-donation is expected to be more important.[6]

- Investigating the effects of changing one (or more) ligands is also of interest. In the common picture having co-ligands which are good π-acceptors (such as NO, CN- or NO2-) contribute to a higher carbonyl frequency due to competition for electron density, while co-ligands which are good π-donors(such as I-, Br- and SCN-) will have a lower carbonyl frequency. Therefore the completed study and also the additional research routes mentioned above could be extended by changing one of the carbonyl ligands for a series of other ligands. In these cases it would be more interesting to look at the electronics as the complexes will no longer be symmetrical and to see how the MOs change due to having a different ligand(s).

- Further in the study of alternative ligands is the position that the ligand assumes in the complex. It has been suggested from experimental evidence that strong π-acceptors prefer the equatorial position while σ-donors prefer the axial position. The validity of this statement as well as the reasoning behind these preferences would be another engaging area of additional study.

- As M-C bonds can also be clearly viewed using computational methods, it would be possible to analyse the bonding by focusing on this bond as well (instead of the C-O bond which is commonly used as it is clearly visible on IR spectra as its stretching frequency occurs in a region where N-N and N-O stretches are generally the only other vibrations which would also occur in this region)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 3.I3 Advanced Organometallic Chemistry, Year 3 Autumn Lectures, Dr. Wilton-Ely and Dr. Diez-Gonzalez, 2011-2012

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedrefcrc3 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedrefcrc5 - ↑ Dissociation Energies, Vibrational Frequencies, and 13C NMR Chemical Shifts of the 18-Electron Species [M(CO)6]n (M = Hf-Ir, Mo, Tc, Ru, Cr, Mn, Fe) DOI:10.1021/ic970223z

- ↑ Molecular Orbitals in Inorganic Chemistry, Year 2 Autumn Lectures, Dr. P Hunt, 2011-2012, Lecture 8

- ↑ Theoretical Studies of Organometallic Compounds. Ligand Site Preference in Iron Tetracarbonyl Complexes Fe(CO)4L (L = CO, CS, N2, NO+, CN-, NC-, ɳ2-C2H4, ɳ2-C2H2, CCH2, CH2, CF2, NH3, NF3, PH3, PF3, ɳ2-H2) DOI:<985::AID-ZAAC985>3.0.CO;2-# 10.1002/1521-3749(200105)627:5<985::AID-ZAAC985>3.0.CO;2-#