Mod:Retribution

Module 2

Owen Davis

Introduction and Aims

The bonding in many inorganic complexes and compounds is not straightforward. Therefore, computational chemistry is used to give an insight into the structure and bonding of various inorganic complexes. These computational studies can help differentiate between conformers, for example by comparing the energy of the stable conformers. However, what is even more important is that computational chemistry can allow chemists to locate transition states and activated complexes, which might be impossible to characterise experimentally. Thermodynamic information can also be obtained from the energy of various transition states and the energy of the stable states. Albeit harder, it is also possible to obtain kinetic data.

Many properties of the various molecules and complexes can also be calculated. These include both infra-red and NMR spectra.

In this module, various inorganic molecules and complexes will be optimised using Gaussian. Following this, the various properties of these molecules will be calculated in order to determine the type of bonding, reactivity and stability of these molecules, as well as many more properties.

Inorganic Computational Techniques

Borane

Introduction

Boron is a Group 13 element, and therefore has 6 valence electrons, with an empty p-orbital. It is because of this that borane (BH3) is expected to have a planar structure in a singlet ground state[1]. It is this empty p-orbital in borane that explains its extreme reactivity as a Lewis acid. Borane can easily accept electrons into this empty p-orbital. As a result, borane readily and rapidly dimerises to the more stable diborane (B2H6), as seen in Figure 1. This is a prime example of electron-deficient three-centre bonding[2].

Boranes usually exist in the form of clusters, which have all been extensively studied, and have a wide variety of applications. A good example is the use of boron neutron capture therapy for tumours [3]. However, a result of its extremely high reactivity, borane has been studied very litte. However, it has received some attention in the field of organic synthesis, as borane can stereochemically reduce carbonyls[4].

In this section, the various tools available in GaussView will be explored in order to determine the most stable structure of borane, as well as explaining various physical properties, such as its lewis acidity, by calculating and then analysing its molecular orbitals.

Optimisation

|

Using GaussView3, borane (BH3) was drawn and the bond lengths manually augmented to 1.50Å. Gaussian was then used to optimise this structure to its lowest energy. During the process of optimisation, a minimum in the potential energy surface is being determined. This is done by solving the Schrödinger equation for the nuclear positions and electrons. This calculates the energy of the molecule. The atoms are then slightly shifted and the Schrödinger equation is solved again to give a new energy. The two energies are compared, and if the new energy is lower, the process is repeated but from the new nuclear configuration. As a result, the lowest energy structure (minimum in the potential energy surface) is gradually reached.

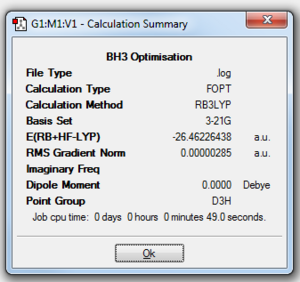

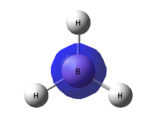

The method used for the borane optimisation was DFT-B3LYP. This method determines what approximations were used in solving the Schrödinger equation. The basis set used was 3-21G. This determines the accuracy of the calculations computed. The basis set used has the lowest accuracy, which is good for initial optimisations, but bad for more complex molecules. The reason for using the 3-21G basis set was to reduce the computational time of the calculations run. The optimised structure of borane is shown in Figure 2 and the output file can be found above or here

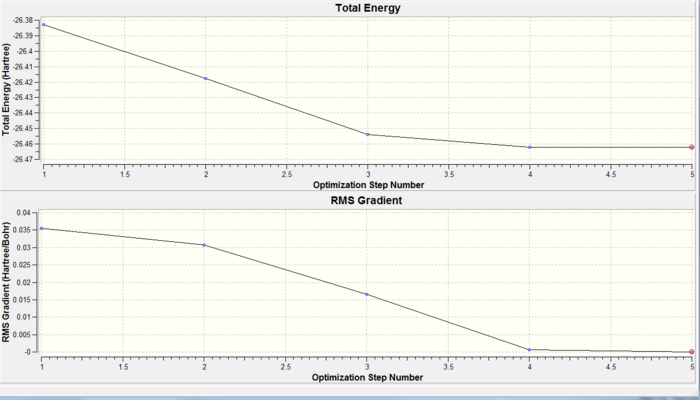

Figure 3 shows the summary details of the optimisation calculation. It can be clearly seen that the RMS gradient is less than 0.001. This shows that the optimisation reached completion. The energy term in Figure 3 is measured in the atomic unit of energy, Hartrees (1 Eh = 4.359 743 94×10−18 J[5]). This energy term corresponds to the energy of the optimised structure of borane, i.e. the minimum energy structure.

Figure 4 is a graphical representation of the Gaussian program travelling along the potential energy surface of borane and finding the minimum energy structure, as well as the RMS gradient during this optimisation. From Figure 4, it can be seen that the optimisation reached a minimum energy structure in 5 steps, as the gradient almost reaches zero by the 5th step. This RMS gradient shows the deviation from the ideal bond length at each optimisation step.

Each subsequent optimisation step reduces the energy of the borane structure and the RMS gradient approaches zero, where the optimisation terminates. Figure 5 shows an animated version of the optimisation steps of borane.

After the optimisation, the average B-H bond length was calculated as 1.19Å with a bond angle of 120°, which is exactly the same as the literature value[6].

Molecular Orbital Analysis

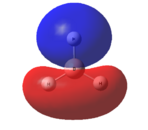

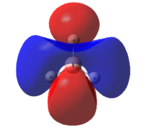

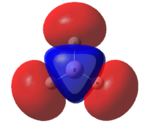

This optimised structure of borane was used to calculate the molecular orbitals of borane[7], which can be seen in Figures 6 and 7 where were determined by qualitative LCAO theory and Gaussian respectively.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It can be clearly seen by comparing the two figures above, that there is a good relationship between the molecular orbitals calculated via the computational methods and those determined using molecular orbital theory.

| Molecular Orbital |

Energy / Eh |

|---|---|

| 3a1’ | 0.191 |

| 2e’ | 0.188 |

| 2e’ | 0.188 |

| 1a2" | 0.074 |

| 1e’ | -0.356 |

| 1e’ | -0.356 |

| 2a1' | -0.517 |

| 1a1' | -6.730 |

It can be seen (in Table 1) that the 1s orbital of boron is so low in energy that it does not combine with any other orbitals, despite having the same symmetry label as others. This can be clearly seen in Figure 6, as the 1a1' orbital is represented by the localised 1s orbital. As a result of this, the less diffuse, higher in energy 2s orbital of boron interacts strongly with the 1s orbitals of the 3 hydrogen atoms. This gives rise to the expected shape of the orbitals, as determined in Figure 5. Unlike using LCAO to determine the molecular orbitals, the computational method shows the various atomic orbitals mixed, and therefore shows the orbitals appearing to be merged together. This is useful, as it allows people to visualise the shapes of the various molecular orbitals more easily compared with the LCAO method.

Unfortunately, this computational method has some limitations. One of these is that the two highest anti-bonding orbtials (2e’ and 3a1’) can be reversed interchangeably, and therefore they are difficult to evaluate. This is due to the fact that the energies of these orbitals (as seen in Table 1) are very similar, the difference being 0.003 Eh. This is very small compared with the rest of the molecular orbitals, which have much larger energy differences. The relative energy levels of the two highest antibonding orbitals can be explained by two different approaches. Firstly, it is expected that the s-s interactions are stronger than the s-p interactions (due to greater amounts of overlap). Therefore, as the s-s interactions are stronger, it means that the antibonding orbital attributed to these orbitals mixing (3a1’) would be destabilised more than the 2e’ orbitals and therefore be higher in energy.

Secondly however the atomic orbitals which mix to form the 3a1’ orbital (the a1’ atomic orbitals) are far lower in energy than the e’ atomic orbitals. From this analysis, it would be expected that the 3a1’ orbital would be lower in energy than the degenerate 2e’ orbitals.

It can be seen from Figure 7 and Table 1 that the computational method has calculated that the s-s interactions outweigh the fact that the a1’ atomic orbitals are lower in energy. As a result, the antibonding 3a1’ orbital is the most destabilised orbital and therefore appears higher in energy than the 2e’ orbitals in Figure 6.

Natural Bond Order Analysis

When the molecular orbitals of borane were calculated using Gaussian, the additional keyword of NBO was added by selecting the “Full NBO” option in GaussView. This allowed the natural bond order to be computed and therefore analysed. Not only does this analysis give the charge distribution of the molecule, but it also details the type of bonding used in the molecule, i.e. sp2, sp3, etc.

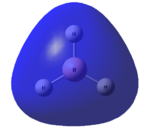

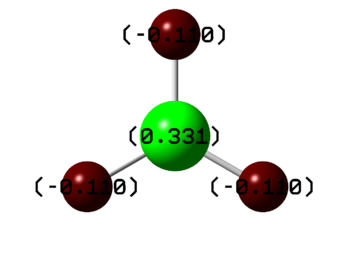

The graphical representation of the charge distribution is shown in Figure 8.

The different colours in Figure 8 correspond to areas of differing charge in the molecule. The bright green areas correspond to areas of differing electron density. The bright red areas correspond to atoms with highly negative charge. This colouring implies that the boron atom is highly positively charged. This is indeed the case as, in borane, boron is electron deficient and acts as a lewis acid. Despite the colouring making it difficult to see the numbers, it is clear that the charge distributions on the boron and hydrogen atoms have been calculated to be 0.331 and -0.110 respectively. This again confirms the fact that the boron atom is highly positively charged, but it also confirms that overall the molecule is neutral. This is due to the fact that these numerical charges cancel each other out.

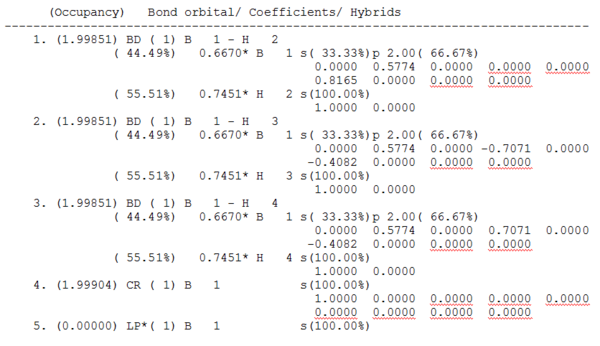

Unfortunately, the graphical representation in Figure 8 does not give any details about the type of bonding involved in the molecule. In order to analyse this, the .log file[7] must be consulted. The relevant information found in the .log file is shown in Figure 9[7].

Despite the apparent complexity of this output, the information clearly shows that the boron orbitals contribute 44.49% to each B-H bond, and that 55.1% of each B-H bond is contributed by the H-orbital. The information shown in Figure 9 also tells us the hybridisation of the boron orbital. It comprises of 33%s and 66%p. This shows that the boron atom has formed 3 sp2 orbitals which each interact with the atomic s-orbitals of one hydrogen atom. Finally, it shows that the boron has a p-orbital which is unoccupied (shown by the *).

This is all expected for a borane molecule. This is because BH3 is trigonal planar, which means that each of the bonds is sp2 hybridised, with the remaining unoccupied p-orbital perpendicular to the plane of the molecule. This empty p-orbital allows borane to act as a lewis acid and accept electrons.

Vibrational Analysis

| Vibration | Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Intensity | Vibrational Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1146 | 93 | A2" |

|

|

1205 | 12 | E' |

|

|

1205 | 12 | E' |

|

|

2593 | 0 | A1' |

|

|

2731 | 104 | E' |

|

|

2731 | 104 | E' |

The fully optimised structure of borane was used to carry out the frequency analysis. Not only did this allow the infra-red spectrum of BH3 to be calculated, but it also allows us to confirm that the optimised structure obtained is indeed the most stable structure, i.e. has the lowest energy. This involves a calculation which computes the second derivative, which gives the curvature of the potential energy surface (which are the frequencies of the molecule). This result can show if the structure is indeed a minimum in energy. If all the second derivatives (frequencies) are positive, it is an energy minimum. However, if one of the frequencies is negative, it implies that the geometry found is that for a transition state. Finally, if all the second derivatives are negative, it is an energy maximum. This means that a critical point was not found and the optimisation calculation most likely failed. In this scenario, more optimisation calculations would have to be conducted. The calculated vibrations are shown in Table 2 and the resulting IR spectrum in Figure 10.

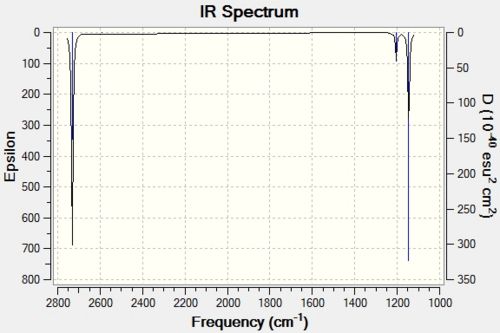

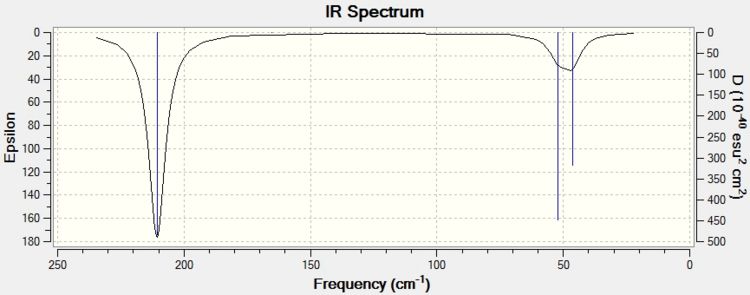

It can be clearly seen from Table 2 that 6 vibrations were calculated. This is what was expected for non-linear molecules due to the 3N-6 rule (in this case N = 4). However, it can be clearly seen from the computed IR spectrum of BH3 (Figure 10) that only 3 peaks are visible. These are at 1146cm-1, 1205cm-1 and 2731cm-1. By inspecting the vibrations calculated, the difference between these and the calculated spectra can be deduced.

From the calculations, it is shown that A1' vibration has an intensity of zero. This is due to the fact that this vibration is a symmetric stretch. Therefore, there is no change in the overall dipole moment of the molecule. As a result, this symmetric stretch is not infra-red active and therefore it is not seen.

Also, it can be seen that there are degenerate scissoring and rocking vibrations as well as the two asymmetrical stretches. This is clearly shown by each of these vibrations having the symmetry label E'. This degeneracy is also shown by the fact that they have the same vibrational frequencies (1205cm-1 and 2731cm-1 respectively) as well as the same intensities (12 and 104 respectively). These degenerate vibrations as well as the A2" vibration (wagging) are responsible for the 3 vibrationally active peaks seen in the IR spectrum. The asymmetric stretches require the largest amount of energy and therefore correspond to the highest frequency peak (2731cm-1). The wagging vibration will require the least energy and therefore corresponds to the peak at 1146cm-1. From a process of elimination, this leaves the peak at 1205cm-1 to correspond to the degenerate scissoring and rocking vibrations.

Thallium (III) Bromide

Introduction

Thallium (III) bromide is an unstable compound with disproportionates to TlBr2 at less than 40°C and has been known of since the late 1800s[8]. Thallium (III) bromide can be prepared in CH3CN by treating a solution of TlBr with bromine gas. These type of complexes tend to be strong, due to the strong interactions between the highly charged heavy metal ions and the electron-pair donor ligands[9]. This allows detailed structures to be determined from crystals, but it is much more difficult to obtain data of the structure when in solution.

In this section of the report, new methods and basis sets will be used to calculate the optimised structure of thallium (III) bromide and some of its physical properties, as well as its spectra. This will show how accurate some of the pseudo-potential basis sets can be, especially when concerned with complexes with a large number of electrons.

Optimisation

Thallium (III) Bromide Optimisation

Thallium tribromide was drawn in GaussView3 but, rather than manually manipulating the bond lengths as was done for borane, they were left unchanged. However, the symmetry was set to the D3h point group. This was tightly confined in order to prevent the optimised geometry of thallium tribromide from drifting from this D3h symmetry. As with borane, calculations were carried out in order to optimise the geometry of the molecule. However, rather than using the low accuracy 3-21G basis set, the pseudo-potential basis set LANL2DZ was used. This is a medium level basis set and is used when heavier elements are involved. The reason why the 3-21G basis set was not used was because it considers each electron in the molecule. Although this is acceptable for small molecules (such as borane, which only has 8 electrons), using it for the various calculations of thallium tribromide would be too time consuming (as TlBr3 has 186 electrons). Therefore, a pseudo-potential must be used to model the core electrons, as the valence electrons are assumed to dominate in the various bonding actions. As a result, this makes the calculations a lot easier and faster to carry out. The downside to this is that the results are not as accurate, but they are still accurate enough to yield decent optimisation data.

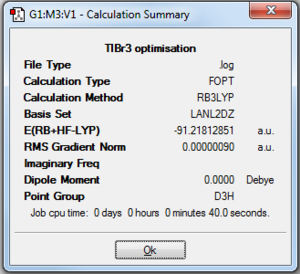

Therefore, the geometry of thallium tribromide was optimised using the DFT-B3LYP method with the LANL2DZ basis set. The optimised structure is shown in Figure 12, with the summary details of the optimisation shown in Figure 11. Finally, the output file can be found here.

| Figure 12: Optimised TlBr3 | |||

|

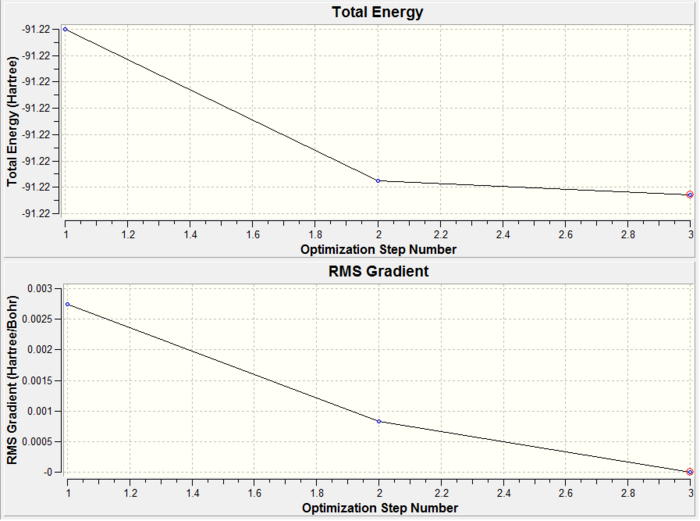

From Figures 11 and 14, it can be clearly seen that the RMS gradient is less than 0.001. This shows that the optimisation reached completion. Figure 14 shows the graphical representation of the Gaussian program travelling along the potential energy surface of thallium (III) bromide and finding the minimum energy structure, as well as the RMS gradient during this optimisation. What is noticeable is that it only took 3 steps to optimise the structure of thallium tribromide to its lowest energy configuration. This structure had a Tl-Br bond length of 2.65 Å and a bond angle of 120°. This compare very well to the literature values[10] of 2.55Å and 120°.

Finally, the animated optimisation steps can be seen in Figure 13. Compared with the optimisation of borane, the bonds do not disappear (as shown in Figure 5). The reason for the bonds “disappearing” in GaussView is because they are based on a distance criteria. If there are no bonds seen, then it means that the bond distance exceeds that of the pre-defined value used in GaussView. This is seen frequently when computing inorganic complexes, as the bond lengths are usually longer than those seen in organic molecules. A covalent bond can be simply described as the sharing of pairs of electrons between atoms. However, a covalent bond can be seen as a stable balance between the attractive and repulsive forces between atoms when they share electrons[11].

Vibrational Analysis

Thallium (III) Bromide Vibrational Analysis

To be certain that the optimised geometry calculated has the lowest energy possible, vibrational analysis was carried out using the same method and basis set as before (DFT-B3LYP and LANL2DZ). Using the same method and basis set allows the two resulting calculations to be compared as the calculations done are all relative. Therefore, using either a different method or basis set would give nonsensical results.

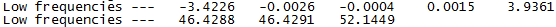

Figure 15 shows an excerpt from the .log file which shows the ‘low frequencies’. The first line of these frequencies corresponds to the motions of the centre of mass of the molecule. These motions are the 6 degrees of freedom accessible and are effectively the -6 term in the 3N-6 equation. Ideally, these 6 values should be as close to zero as possible. This would show that the method employed is accurate. However in practice, they are usually required to be within +/- 10cm-1, which they all are. The second line corresponds to the vibrational frequencies shown by the molecule. The fact that these are all positive shows that the correct minimum has been reached.

Comparison of TlBr3 with BH3

| Vibration | Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Intensity | Vibrational Symmetry Label |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

46 | 4 | E' |

|

|

46 | 4 | E' |

|

|

52 | 6 | A2" |

|

|

165 | 0 | A1' |

|

|

211 | 25 | E' |

|

|

211 | 25 | E' |

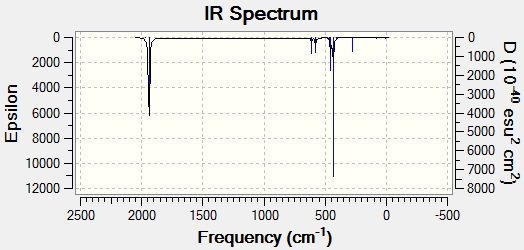

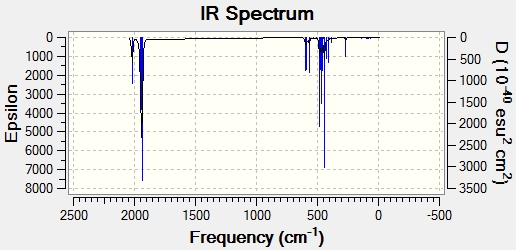

Both TlBr3 and BH3 show 6 vibrational modes, which is expected due to the 3N-6 rule. However, these vibrational modes are all at a much lower frequency for TlBr3 than for BH3. This lower frequency implies that the Tl-Br bond is much weaker than the B-H bond. This is supported by the fact that the Tl-Br bond is much longer than the B-H bond (the difference being 1.46 Å). The reason for this is due to the orbitals involved in the bonding. For BH3, the orbitals involved are the 1s (from the hydrogen) and the 2sp3 (from the boron) orbitals. These are localised and therefore have a large amount of overlap, producing strong bonds. However, in TlBr3 there are more electrons, which means that the orbitals used for bonding will be more diffuse and therefore overlap less, producing weaker bonds.

Another interesting point of difference is that, for TlBr3, the wagging vibrational mode is not the lowest energy vibrational mode as it was in BH3. The degenerate scissoring and rocking modes are. This is most likely due to the increase in the bond length. This would mean that more energy is required to move the bromine atoms in the direction shown in Table 3, as they are further away from the thallium atom. In effect, it is acting similar to a lever, i.e. the force applied at each end point of the bond is proportional to the ratio of the length of the bond and the force applied at the end end of the bond.

Stereoisomers of Mo(CO)4Cl2

Introduction

Disubstituted molybdenum tetracarbonyl octahedral complexes have been shown to exhibit both cis and trans stereochemistries. It has also been shown that the when the ligand is triphenyl phosphine (PPh3), the cis- isomer thermally rearranges completely to form the trans isomer. This is done via a dissociate process involving the cleavage of an Mo-P bond[12]. The reason for this is that the trans isomer is the thermodynamically more stable form[13].

However, it has also been shown that, at room temperature, photochemical isomerisation occurs to form the cis-isomer[14]. Therefore, it can be predicted that this isomerisation between the cis- and trans- isomers depends on both the steric and electronic properties of the ligand, L.

In this section of the module, these isomers will be modelled in order to determine which will be the most favoured to form by taking into account electronic and steric properties. The infra-red spectra of both molecules will be calculated as well, in order to determine how accurate the calculations performed are. This is because the cis- and trans- isomers should have different numbers of carbonyl stretches, as they have different symmetries.

Unfortunately, if the ligand used in the calculations was PPh3, the computing resources would be too expensive (in terms of both time and cost). Therefore, the phenyl rings were replaced with chlorine atoms. These have been shown to have similar electronic contribution to the bonding as phenyl groups do and they are sterically bulky. This, combined with the fact that they are computationally less demanding, makes them a prime candidate for replacing the phenyl rings in the phosphine ligands.

Optimisation

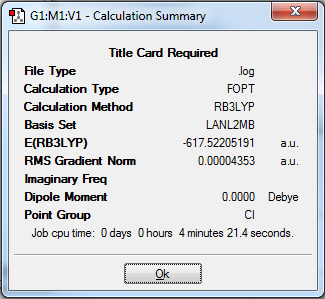

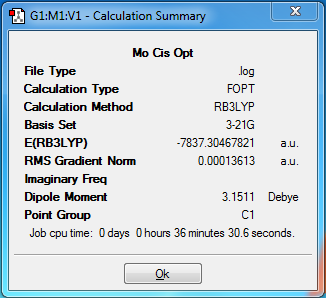

In order to optimise the complexes to a sufficient degree of accuracy, the optimisation had to be carried out in three stages. All of the optimisation stages used the same method, which was B3LYP. However, the basis sets used differed. The first optimisation utilised the low lever basis set LANL2MB, with the additional keyword ‘opt=loose’. This basis set was used in order to obtain an approximate optimisation and the keyword was added in order to prevent the convergence criteria from being more accurate than the method used. The structure and summary data of the molecules after the first optimisation can be seen below in Figures 17 and 18:

|

| ||||||||||||||

After this optimisation, all of the phosphorous chlorine bonds had disappeared. This was due to the fact that these bonds are longer than the distance criteria pre-programmed into GaussView, as explained earlier. In order to continue onto the second optimisation, these bonds had to be redrawn into GaussView.

Each of the isomers had to have its geometry altered in order for Guassian to calculate the actual minimum energy structure of each of the isomers more easily. For the trans- isomer, the PCl3 ligands had to be orientated so that they were eclipsing one another, and also so that one of the P-Cl bonds was parallel to a Mo-C bond. The altered geometry for the trans- isomer can be seen in Figure 19.

For the cis-isomer, one of the P-Cl bonds on one of the PCl3 ligands was positioned syn-periplanar to the axial Mo-C bond. On the other PCl3 ligand, a P-Cl bond was positioned anti-periplanar to the same axial Mo-C bond. This gave torsional angles of 0° and 180° respectively. This altered structure can be seen in Figure 20.

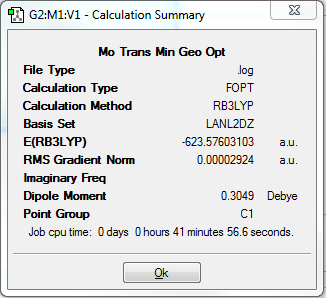

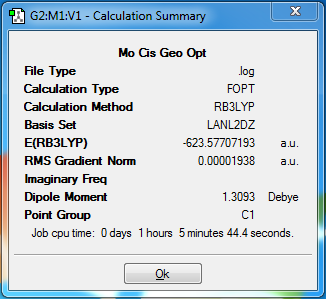

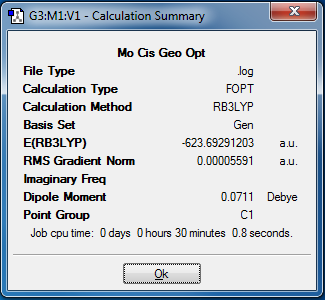

After this adjustment, the second optimisation was performed using the pseudo-potential LANL2DZ basis set, with the addional keywords ‘int=ultrafine scf=conver=9’. These were used as they produced a more accurate optimisation with tighter convergence criteria. The resulting structures after this second optimisation are shown in Figures 21 and 22.

|

| ||||||||||||||

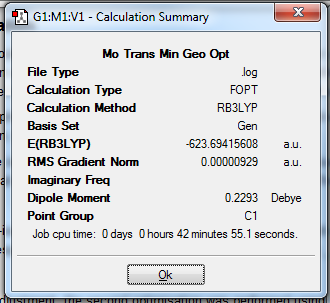

Once again it can be seen that GaussView had not inserted the P-Cl bonds. As was done previously, these bonds were redrawn in order to continue onto the final optimisation. This final optimisation takes into account that phosphorous atoms tend to use their low lying d-orbitals and therefore prefer being hypervalent (which the previous basis sets ignored). Therefore, this final optimisation includes d-atomic orbital functions and as a result will give more accurate results. However, this could not be done using GaussView, and the input file had to be manually edited with the keyword ‘extrabasis’ at the beginning of the file, as well as text at the end of the file telling Gaussian to add a P atom and a D function of a specific width (0.55) and decay rate (0.100D+01). This augmented input file was used for the third and final optimisation. The resulting structures after these final optimisations contained P-Cl bonds and they are shown in Figures 23 and 24.

|

| ||||||||||||||

Energy Analysis

| Isomer | Energy /Eh |

|---|---|

|

Trans- |

-623.694 |

|

Cis- |

-623.693 |

Comparing the relative energies of the cis- and trans- isomers after the final optimisation (as seen in Table 4) shows that the trans-isomer has a slightly more negative energy. The energy difference between the two isomers is 2.6 kJmol-1. This means that the trans- isomer is more stable. However, as this difference is of the same magnitude as the energy at room temperature, these isomers are likely to interconvert at room temperature. The most likely cause for the trans- isomer being more stable is due to sterics.

The PCl3 ligands are very bulky and will therefore sterically interact with each other when they are in the cis- conformation. This would increase the energy of the molecule. However, in the trans- isomer, the bulky PCl3 ligands are in the axial positions, which means that they are as far away from each other as possible. Therefore these steric interactions do not occur and the trans- isomer is more stable.

If it was wished to reverse this stability, the cis- isomer would have to be made more stable than the trans-. In order to do this, a favourable interaction between the potentially cis- ligands must exist in order to overcome any unfavourable steric interactions they might have. An example of this would be hydrogen bonding. If the two ligands could hydrogen bond to each other, then the most stable isomer would be the cis- isomer, as the ligands would hydrogen bond and, as a result, lower the energy of the cis- isomer. Therefore, if it was wished to do this, ligands which can hydrogen bond should replace the PCl3 ligands. A classic example of this would be to use water molecules as ligands.

Geometry Analysis

Within GaussView, geometric parameters such as bond lengths and bond angles can be determined. For this exercise, the P-Mo bond lengths and the P-Mo-P bond angles have been measured for both of the isomers. These results and their literature values[21] are summarised in Table 5.

| Bond Length (Mo-P) / Å |

Bond Angle (P-Mo-P) / ° | |||

| Isomer | Calculated | Literature[21] | Calculated | Literature[21] |

| Trans- | 2.42 | 2.50 | 177 | 180 |

| Cis- | 2.48 | 2.58 | 94 | 105 |

It can be clearly seen that the Mo-P bond length of the trans- isomer is slighty shorter than that of the cis- (all of 0.06 Å). The reason for this slight elongation of the cis- isomer Mo-P bonds is most likely due to the unfavourable steric interactions seen between the PCl3 ligands in the cis- isomer. This causes the ligands to repel each other and therefore, in order to get as far away from each other as possible, slightly lengthen the bond. Both of these computed values correspond relatively well with literature values[21], but both are calculated to be shorter. This difference is most likely due to the fact that the literature values are for the [Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2] complex rather than the [Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2] complex that was computed in this exercise.

Like the bond lengths, the P-Mo-P bond angles correspond relatively well with the literature values, but again the calculated angles are underestimated. This difference is again most likely due to the fact that two different complexes are being compared. As PPh3 ligands are much bulkier than PCl3 ligands, this means that there will be greater repulsion between the PPh3 ligands and therefore the bond angle would be larger.

Vibrational Analysis

Low Frequencies

To ensure that the optimised geometries obtained were in fact minima rather than transition states, a vibrational analysis was carried out[22][23]. As it can be seen in Table 6, all of the low frequencies were positive. This shows that both of the geometries calculated were in fact minima.

| Trans- Isomer | Cis- Isomer | ||||||

| Low Frequency | Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Energy / kJmol-1 | Intensity | Low Frequency | Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Energy / kJmol-1 | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

4 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

|

12 | 0.14 | 0.0163 |

|

|

7 | 0.08 | 0 |

|

20 | 0.24 | 0.0042 |

|

|

40 | 0.48 | 0.11 |

|

46 | 0.55 | 0.0008 |

As can be seen, all of the low frequency vibrations correspond to rotations of the chlorine atoms on the PCl3 ligands. Table 6 also shows the corresponding energy of each of these vibrational modes, which were calculated using the equation:

where is the energy per mol (kJmol-1), is Plank's Constant, is the speed of light and is the wavenumber (cm-1).

It can be seen that each of these vibrational modes is well below the energy at room temperature (2.5kJmol-1). This means that, at room temperature, it would be expected that these vibrational modes occur. This theory is supported by the fact they these low frequency vibration modes have very low intensities. However, for the trans- isomer, the vibrational mode at 7cm-1 has no intensity. This is due to this mode being symmetric. Therefore there is no change in the overall dipole moment of the molecule and therefore this vibrational mode is not infra-red active.

Carbonyl Stretching Frequencies

Table 7 shows the carbonyl stretching frequencies for both the cis- and trans- isomers as well as their literature values[24].

| Trans- Isomer | Cis- Isomer | ||||||

| Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Literature Frequency / cm-1[24] |

Symmetry Label |

Intensity | Stretching Frequency / cm-1 |

Literature Frequency / cm-1[24] |

Symmetry Label |

Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1896 | Eu | 1606 |

|

1986 | B2 | 1604 |

|

|

1896 | Eu | 1606 |

|

1994 | B1 | 813 |

|

|

- | B1g | 6 |

|

2004 | A1 | 588 |

|

|

- | A1g | 5 |

|

2072 | A1 | 545 |

It is clear from this table that there is a relatively large difference between the computed and literature values (up to 53 cm-1). However, the computational method used has a systematic error of ≈10%. This systematic error is due to the fact that harmonic approximations are used for the vibrations, when in reality they are anharmonic functions. Considering this error, the calculated results are relatively accurate.

|

|

The literature shows that 4 carbonyl peaks can be seen in the IR spectra for the cis-isomer. This is confirmed by the computational result which shows 4, non-degenerate vibrational modes. The 4 expected vibrational modes is due to the fact that the cis- isomer has a symmetry geometry of C2v.

However, for the trans- isomer, the literature reports only two carbonyl peaks (which is expected due to the D4h), whereas the computational methods reports 4 peaks. However, two of these (at 1939 cm-1 and 1940 cm-1) are degenerate. This means that they will appear as one peak on the IR spectrum. Also, there are two extra peaks observed in the calculated results compared with the literature (at 1967 cm-1 and 2026 cm-1). These have very low intensities due to the fact that they are symmetric stretches. These extra peaks are most likely due to the relaxed geometry used in the calculations.

By comparing the computed carbonyl stretching frequencies with that of free carbon monoxide (2158cm-1), it can be clearly seen that for both of the isomers the frequencies of the carbonyl stretches are lower. This shows that, in the complexes, the C=O bond is weaker than in free carbon monoxide. This implies that the metal is back-bonding to the carbonyls. Figure 27 shows the process of metals bonding to carbonyls.

This is as expected, as the PCl3 ligands donate a lone pair to the metal. This increases the electron density at the metal centre, and as a result, makes it easier for backbonding to occur, weakening the C=O bond.

Finally, it can be seen that the carbonyl stretching frequencies of the cis-isomer are slightly lower in wavenumber than those of the trans-isomer. This is most likely due to the trans effect[25]. For the cis- isomer, the PCl3 ligands are trans- to some of the carbonyl ligands, which weakens the bonds in the carbonyl ligand, lowering the stretching frequencies. However, in the trans- isomer, the PCl3 ligands are not trans- to any carbonyl ligands and therefore this trans effect is not seen.

Mini Project

Aims and Introduction

Borazine was first reported by Stock and Pohland[26] by the reaction of diborane with ammonia. However, this synthesis produced relatively poor yields and, in recent years, more effective syntheses have been developed. One of the more modern syntheses is shown in Figure 28.

This product after the first step (trichloroborazine) is, in effect, the inorganic equavalent to 1,3,5-trichlorobenzene. However, unlike trichlorobenzene, trichloroborazine will readily undergo reduction to borazine with the weak reducing agent sodium borohydride. In order for trichlorobenzene to be reduced to benzene, far more exotic reagents must be employed[27]. This difference in reactivity of trichlorobenzene and trichloroborazine will be explored in this mini project.

Borazine has been shown to be a precursor to boron nitride ceramics[28] but, more recently, it and its precursors have been used for hydrogen storage[29], which is extremely important from an energy perspective.

Due to borazine being a cyclic compound, combined with the fact that it is isoelectronic and isostructrual to benzene, borazine has been referred to as ‘inorganic benzene’ and as being aromatic. This is due to the fact that all of the boron nitrogen bonds are the same length, which is in between those of a boron nitrogen single and double bond. Therefore, this suggests delocalisation of the nitrogen lone pair over the entire ring.

However, the reactivity of borazine is very different from that of benzene. For example, borazine can undergo electrophilic and nucleophilic additions, where as benzene only undergoes electrophilic substitution reactions.

In this mini project, the various structural properties of benzene, borazine and their trichloro- derivatives will be calculated to determine how accurate the calculations used are. Also, the reason for the different reactivity of borazine and trichloroborazine compared with their benzene counterparts will be investigated by looking at each of the molecules' molecular orbitals, as well as analysing their infra-red spectra and natural bond orders.

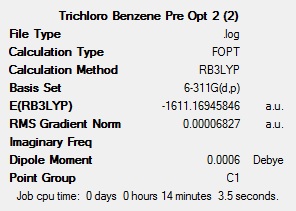

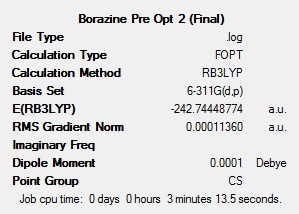

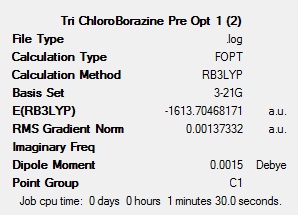

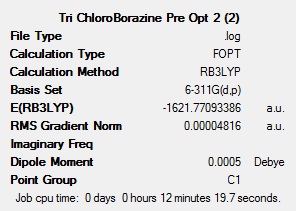

Optimisation

To get a rough optimisation, all four of the molecules were optimised with Gaussian, using the DFT-B3LYP method, with the low accuracy basis set 3-21G. Additional keywords of ‘opt=(loose,maxcycle=50)’ were used to make sure that the convergence criteria were not more accurate than the method used and to ensure that the optimisation converged within 50 cycles to reduce computational times and as a result cost. A second, more accurate optimisation was carried out on the inaccurate optimised molecules. This new optimisation used the same method, but a more accurate basis set (6-311G(d,p)). The ‘d’ allows for diffuse orbitals and the ‘p’ allows for polarisation. Allowing for these produces far more accurate results. The results after each of the optimisations for all 4 molecules can be seen below.

|

|

|

|

The summary tables show that the second optimisation reduced the energy of each of the molecules further. This shows that using the basis set 6-311G(d,p) in the second optimisation was successful and gave more accurate results.

Vibrational Analysis

Vibrational analysis was performed to confirm that the optimised structures obtained were energy minimum structures (by checking the ‘low frequencies’ were positive). This was found to be correct[38][39][40][41].

A number of vibrations which are key to isolating various electronic properties of the bonds were chosen. The vibrations chosen were those corresponding to B-Cl stretches, C-Cl stretches, N-H stretches, B-H stretches and the various ring breathing vibrations (N-, B- and C-). These can all be seen in Tables 8 to 10 below.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interestingly, it can be seen that the chlorine substituents on the benzene ring inhibit the motion of the ring breathing motion. Only the 3 non-substituted carbon atoms are involved in this vibrational mode. Also, this ring breathing motion has a lower frequency in the trichlorobenzene molecule. This is due to the difference in the reduced mass of benzene and trichlorobenzene:

where is the frequency, is the force constant and is the reduced mass. For benzene, is small and is large. Therefore, it will have the largest observed frequency. Due to the fact that these ring breathing motions are symmetric, their intensity is zero.

For borazine and trichloroborazine, the B-Cl stretches are much weaker than the B-H stretches. This is due to the 1s orbital on hydrogen being localised. This leads to much better overlap between orbitals for boron and hydrogen, which leads to stronger bonds. As a side note, the N-H stretches between each molecule remain approximately the same.

What is interesting is that the nitrogen ring breathing vibrations have slightly higher frequencies for the trichloroborazine than for the borazine. This is due to the fact that the chlorine substituents withdraw electron density from the boron and therefore increase its lewis acidity. This encourages a larger degree of donation from the nitrogen lone pair into the empty boron p-orbital, strengthening the B-N bond. However, the opposite effect is seen for the boron ring breathing vibrations.

Finally, the C-Cl bond stretches are larger than those of the B-Cl bond. This shows that the B-Cl bond is weaker and therefore more likely to break. The reason for this is due to electronegativity differences. For carbon and chlorine it is 0.61, but for boron and chlorine it is almost double at 1.12. This means that the chlorine atom draws the electrons in the B-Cl bond closer to the chlorine than it does in the C-Cl bond. This weakens the bond, and therefore makes it easier for nucleophilic substitution to occur.

Geometry Analysis

From Table 11, it can be seen that all of the B-N bonds in borazine are equal in length. Combined with the fact that it is a planar molecule (D3h) and that there are 6 π-electrons (from the nitrogen lone pairs), using Hückel’s Rule[42] borazine should be aromatic. Also, the bond lengths for borazine and benzene are very close to their literature values of 1.44Å[43] and 1.39Å[44] respectively. This also implies that the B-N bonds are slightly weaker than the C-C bonds. Therefore, this means that even though borazine might be considered aromatic, it is not as aromatic as benzene.

Also, the C-Cl bond is shorter than the B-Cl bond. This implies that the B-Cl bond is weaker. This is most likely due to the electronegativity difference explained above.

| Bond Length / Å | ||||

| Molecule | C-C Bond | C-Cl Bond | B-N Bond | B-Cl Bond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

1.39 | - | - | - |

|

|

1.39 | 1.75 | - | - |

|

|

- | - | 1.43 | - |

|

|

- | - | 1.43 | 1.79 |

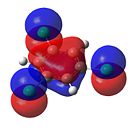

Molecular Orbital Analysis

This analysis will explain why borazine is more reactive than benzene and why trichloroborazine reacts with sodium borohydride (NaBH4) while trichlorobenzene does not. This will be done by focusing on the π-orbtials and ignoring the σ-skeleton.

Benzene

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As shown in Figure 33, all of the carbons contribute equally to the orbitals in the degenerate HOMO and LUMO levels. As seen from the HOMO-1 and HOMO levels, all of the electron density in benzene is situated in the aromatic ring. Therefore, as predicted[46], benzene is not reactive towards nucleophiles.

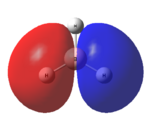

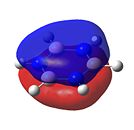

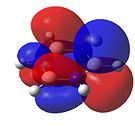

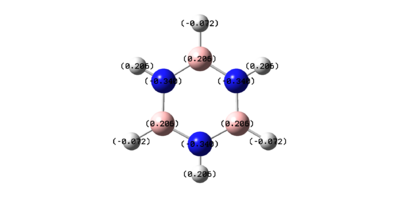

Borazine

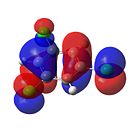

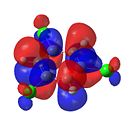

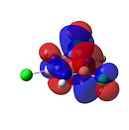

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As can be seen in Figure 34, borazine has a very similar molecular orbital diagram to that of benzene. However, two main differences can be seen:

- The HOMO-LUMO gap is larger for borazine (1.4eV). This implies that borazine is not as conjugated as benzene. This implies that borazine is NOT aromatic.

- The electron density is not dispersed over the entire molecule. It can be seen that for the HOMO levels, the electron density is positioned on the nitrogen atoms. This shows that electrophilic attack will occur at the nitrogen atoms. Also, in the LUMO levels, the orbtials are situated mainly on the boron atoms. This shows that nucleophilic attack will occur at the boron atoms.

Both of these points show that the reactivity of borazine is very different from and much greater than that of benzene. Also, combined with the fact that the electronegativity difference between nitrogen and boron is 1.0, it shows that borazine is not aromatic, as this electronegativity difference implies localised electron density, which is confirmed by the molecular orbitals.

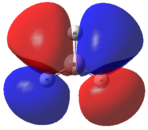

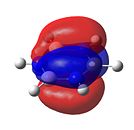

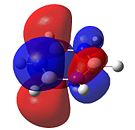

1,3,5-Trichlorobenzene

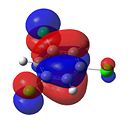

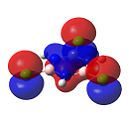

|

|

|

|

|

|

From Figure 35, it can be seen that, like benzene, trichlorobenzene’s orbitals in the degenerate LUMO levels are found to be delocalised over the entire carbon ring. This means that a nucleophile, such as hydride (H-), would not attack the C-Cl carbons over the C-H carbons. Also, the electron density is delocalised over the entire aromatic ring. This can be seen in the HOMO levels. This would repel any nucleophilic attack on the benzene ring. Finally, it can be seen that there is an additional node in the HOMO and LUMO levels compared with benzene. This is due to the additional electron density found on the chlorine atom.

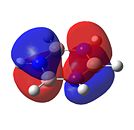

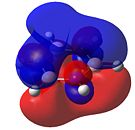

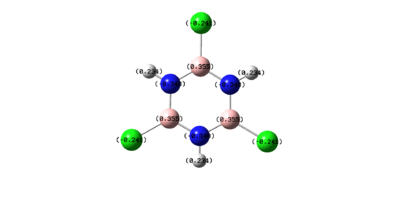

Trichloroborazine

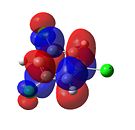

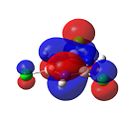

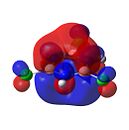

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 36 shows the molecular orbtials of trichloroborazine. For nucleophilic attack to occur on the boron atoms, the LUMO orbitals must be localised on the boron atoms. It can be clearly seen that this is indeed the case. The large size of these orbitals shows that this attack of a nucleophile would occur readily to form borazine.

As in borazine, the electron density is clearly found on the nitrogen atoms. This would again lead to electrophilic attack at the nitrogens.

However, this differs from trichlorobenzene. Trichlorobenzene has electron density dispersed over the entire ring. Due to this dispersion, the nucleophiles are more likely to be repelled and therefore nucleophilic reactions are not seen. On the other hand, electrophilic substitution would clearly be seen, which would be directed to the ortho- positions due to the ortho- para- directing abilities of the chlorine substituents (the para- positions are blocked by the other chlorine substituents).

NBO Analysis

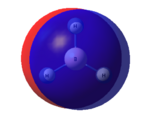

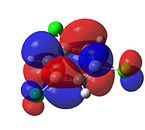

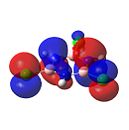

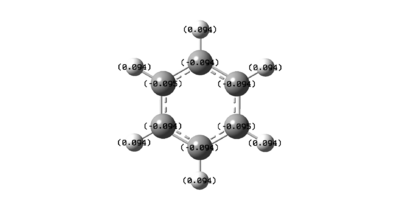

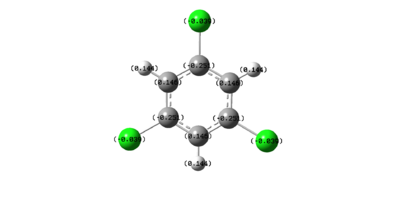

|

|

|

|

Figure 37 shows that, as expected, the carbons in benzene are all slightly negatively charged. This is due to the presence of the delocalised π-electrons. This results in the protons all being slightly positively charged.

However, for borazine the nitrogen and boron atoms do not have equal charge density. The boron atoms are positively charged and the nitrogen atoms are negatively charged. This shows that borazine is more reactive than benzene, as it can undergo both nucleophilic additions at the boron atoms as well as electrophilic additions at the nitrogen atoms. This is in contrast to benzene’s electrophilic substitution reactions.

It has been shown that trichloroborazine is readily reduced to benzene using the weak reducing agent sodium borohydride. However, under the same reaction conditions, trichlorobenzene will not be reduced to benzene. For this to be achieved, different reagents and conditions must be utilised. It has recently been shown [27] that catalytic amounts of subnanometrical Ni-Al clusters produce relatively high yields of benzene in the reductive dehalogenation of trichlorobenzene.

From analysing the graphical displays of the NBOs, this reactivity can be explained. They clearly show that, in trichlorobenzene, the carbons bonded to the chlorines are negatively charged. This seems counter intuitive as chlorine atoms are electronegative. This means that they should accept electron density from the aromatic ring, making the carbons positively charged. This is the opposite of what is seen here. This is because the lone pairs on the chlorine atoms can resonantly donate into the aromatic ring. This would cause the carbon atoms to be negatively charged. This means that these carbon atoms would not be susceptible to nucleophilic attack as the negatively charged carbon atoms would repel them. Therefore, trichlorobenzene would not be reduced to benzene using sodium borohydride.

However, in trichloroborazine, the chlorine atoms make the boron atoms even more positively charged. This is once again due to this inductive electron withdrawing effect. This makes the boron atoms even more susceptible to nucleophilic attack and therefore trichloroborazine would easily be reduced to borazine with sodium borohydride.

Conclusion

The computational methods used in this mini-project were able not only to confirm that borazine and trichloroborazine are more reactive than benzene and trichlorobenzene respectively, but also to explain why this is so. However, is has been shown[50] that it is not possible to explain the reactivity of borazine and borazine derivatives by solely considering the π-orbitals. Therefore, in order to properly explain the reactivity, the σ-skeleton orbitals would also have to be considered. Also, analysing the various data shows that borazine is not in fact aromatic and therefore cannot be described as "inorganic benzene". Finally, the data obtained correlated well with literature values. This shows that the methods used to obtain this data were accurate.

Overall Conclusion

In this module various computational methods have been used to accurately and reliably predict the structures and properties of various inorganic molecules and complexes in a quick and simple manner.

In the mini project, it was shown that these computational methods can accurately predict the structure of benzene, borazine and their trichloro- derivatives. These techniques were also able to explain the differing reactivity between these molecules, which matched well to experimental results.

References

- ↑ A. D. Walsh, J. Chem. Soc., 1953, 2296-2301: DOI:10.1039/JR9530002296

- ↑ E. Meutterties, Boron Hydride Chemistry, Academic Press: New York, 1975

- ↑ J. Plesek, Chem. Rev., 1992, 92 (2), 269

- ↑ T. Harada, Y. Matsuda, S. Imanaka, A. Oku, J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 1990, 1641-1643 DOI:10.1039/C39900001641

- ↑ P. J. Mohr, B. N. Taylor, D. B. Newell, Rev. Mod. Phys., 2008, 80, 633-730: DOI:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.633

- ↑ W. Harb, M. F. Ruiz-López, F. Coutrot, C. Grison, P. Coutrot, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2004, 126 (22), 6996-7008: DOI:10.1021/ja031778y

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Published Borane MO Data, DOI:10042/to-7489

- ↑ J. Nickles, Journal de Pharmacie et de Chimie, 1865 , 1, 24

- ↑ J. Blixt, J. Glaser, J. Mink, I. Persson, P. Persson, M. Sandstroem, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1995, 117 (18), 5089–5104 DOI:10.1021/ja00123a011

- ↑ M. Atanasov, D. Reinen, J. Phys. Chem. A, 2001, 105 (22), 5450-5467: DOI:10.1021/jp004511j

- ↑ N. Campbell ,B. Williamson, R. J. Heyden, Biology: Exploring Life, 2006

- ↑ T. D. Magee, C. N. Matthews, T. S. Wang, J. H. Wotiz, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1961, 83, 3200

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, R. L. Kump, Inorg. Chem., 1978, 17, 2680

- ↑ D. J. Darensbourg, M. A. Murphy, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1978, 100, 463

- ↑ Published Trans- Isomer Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7600

- ↑ Published Cis- Isomer Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7601

- ↑ Published Trans- Isomer Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7602

- ↑ Published Cis- Isomer Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7603

- ↑ Published Trans- Isomer Optimisation 3 Data, DOI:10042/to-7604

- ↑ Published Cis- Isomer Optimisation 3 Data, DOI:10042/to-7605

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171

- ↑ Published Trans- Isomer Vibrational Data, DOI:10042/to-7598

- ↑ Published Cis- Isomer Vibrational Data, DOI:10042/to-7599

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Elmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 3864-3873

- ↑ Coe, B. J.; Glenwright, S. J. Coordin. Chem. Rev., 2000, 203, 5-80

- ↑ A. Stock, E. Pohland, Berichte, 1926, 59, 2210–2215

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 F. Massicot, R. Schneider, Y. Fort, S. Illy-Cherrey, O. Tillement, Tetrahedron, 2000, 56 (27), 4765-4768

- ↑ L. G. Sneddon, M. G. L. Mirabelli, A. T. Lynch, P. J. Fazen, K. Su, J. S. Beckdon, Pure & Appl. Chem., 1991, 63 (3), 407-410

- ↑ B. Kröckert, K. van Bonn, P. Paetzold, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 2005, 631 (5), 866-868

- ↑ Published Benzene Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7583

- ↑ Published Benzene Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7590

- ↑ Published Trichlorobenzene Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7584

- ↑ Published Trichlorobenzene Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7589

- ↑ Published Borazine Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7585

- ↑ Published Borazine Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7588

- ↑ Published Trichloroborazine Optimisation 1 Data, DOI:10042/to-7586

- ↑ Published Trichloroborazine Optimisation 2 Data, DOI:10042/to-7587

- ↑ Published Vibrational Analysis of Benzene, DOI:10042/to-7579

- ↑ Published Vibrational Analysis of Trichlorobenzene, DOI:10042/to-7591

- ↑ Published Vibrational Analysis of Borazine, DOI:10042/to-7592

- ↑ Published Vibrational Analysis of Trichloroborazine, DOI:10042/to-7593

- ↑ E. Hückel,Z. Phys. A-Hadron. Nucl., 1932, 76, (9-10), 628-648, DOI:10.1007/BF01341936

- ↑ S. H. Bauer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1938, 60 (3), 24–530 {{DOI|10.1021/ja01270a006)

- ↑ H. Preuss, R. Janoschek, J. Mol. Struct., 1969, 3 (4-5), 423-428 Error: Bad DOI specified!

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Published Molecular Orbitals of Benzene, DOI:10042/10042/to-7594

- ↑ D. R. Stranks, M. L. Heffernan, K. C. Lee Dow, P. T. McTigue, G. R. A. Withers, Chemistry: A structural View, 1970, Carlton, Victoria: Melbourne University Press, 347

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Published Molecular Orbitals of Borazine, DOI:10042/10042/to-7595

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Published Molecular Orbitals of Trichlorobenzene, DOI:10042/10042/to-7596

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Published Molecular Orbitals of Trichloroborazine, DOI:10042/10042/to-7597

- ↑ V. M. Scherr, D. T. Haworth, Theor. Chim. Acta., 1971, 21 (2), 143-148: {{DOI|10.1007/BF00530211}