Mod1DanielPohoryles:Helstad1717

Normal 0 false false false false EN-US X-NONE GU

Modelling using Molecular Mechanics

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Products of the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene (1 and 2)

From the MM2 calculations it can be seen that dimer 2 is thermodynamically less stable then dimer 1 even though it is the main product of the dimerisation reaction. It can hence be concluded that the dimerisation does not rely on the stability of the product but on the transition state stability. It is hence under kinetic control.

Prodcucts of hydrogenation of 2 (3 and 4)

From a thermodynamic point of view the hydrogenation of dimer 2 would give product 4 as it is much more stable compared to 3. The bending term is particularly different for the two products, 4 having a much lower energy. This indicates that the 3-atom angles in product 4 are closer to the “natural” 3-atom angles. Steric strain is hence more important in product 3, “forcing” the atoms into constellations with angles that are not natural. However with respect to torsion, product 3 is more stable. This indicates that the dihedral angles in molecule 3 reduce the torsional strain and create a more favourable energy situation in 3 than in 4. Overall, the Hydrogenation of the double bond that leads to the formation of 4 is hence easier - from a thermodynamic perspective at least.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

Grignard (MgMeI) addition to a derivative of prolinol

In order to understand the regioselctivity of the described addition, the stereochemistry of the compound needs to be assessed. Hence five models of reagent 5 were produced on CHemBio 3D, starting from different points in order to get five slightly differing geometries and to maximise the representability of the results.

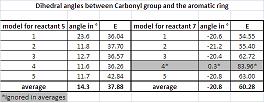

As it can be seen from the five models produced for reactant 5, the carbonyl group always has a dihedral angle of about 10 to 25° (average 14.28°) with the plane of the aromatic ring. The magnesium coordinates hence from the “top” with the Oxygen atom and delivers the Methyl-group from the top of the ring. The stereochemistry is hence nearly always the one described by (6), with the methyl group “sticking out” on the top of the plane of the ring with an angle of about 120° (119.4° on the model predicted by MM2).

Modelling confirms the experimental findings of Schultz et al.[1] which found a very large regioselectivity and stereoselectivity in the addition of the methyl group to the ring with Grignard reagents. The major diastereoisomer resulting from Grignard reagent addition to 5 has the Methyl group oriented anti to the H atom at the chiral center. It can also be observed that the energy of the product is calculated higher by MM2 than the average energy of the five models of the reagent (5). This is an indication that the addition is not thermodynamically driven.

It can also be observed that in MM2 calculations using ChemBio 3D, the Grignard reagent cannot be added into the calculations as Mg is not recognised by the program.

Addition of a bulky group (NHPhenyl) to the pyridinium ring

To understand the regioselecitivity of the addition, again five models of the reagent (7) were created in ChemBio D and the geometry was calculated by MM2. In the product (8), the same stereochemistry can be observed as for the previously discussed Grignard reagent addition. The NHPhenyl group is added from the “top” to the pyridinium ring. However a main difference can be observed in the orientation of the carbonyl group which is on the opposite face of the ring, compared to the face of attack.

The stereocontrol only originates from the orientation of the carbonyl group and this was analysed by computational modelling. The dihedral angle between the carbonyl group and the aromatic ring is about -20° (-20.76° average over 4 models). The orientation of the carbonyl group results from the steric strain of the three bulky methyl groups which are all on the top-face of the molecule and hence “push” the Oxygen out of plane. Only one of the five models presented a different geometry then the one obtained experimentally [2]. However this model has a much higher relative energy (85 compared to about 55 kcal/mol obtained for the other models). It was not taken into account in this discussion.

This reaction is thus strongly controlled by steric factors. The NH2Phenyl group is a very bulky group and hence approaches the pyridinium ring on the opposite face with respect to the C=O. The product predicted by MM2 has the NHPhenyl group on the opposite face to the carbonyl with an angle of 117.8° to the pyridinium ring giving product 8. This result is very consistent with the obtained very high experimental yield of over 95% for the described product [3].

Proposed improvement to the models

As both of the analysed reactions are controlled by stereoelectronic factors, the display of Molecular Orbitals and electron densities would give a much better representation of the situation. The inclusion of Molecular Orbitals would help to understand the steric factors controlling the outcome of these reactions.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

The two possible key reaction intermediates of the total synthesis of Taxol were analysed using molecular mechanics. The most stable isomer seemed to be intermediate 10, with a relative energy of 48.18 in comparison to 91.45 kcal/mol. After some manual changes in the structures of the two isomers, especially by moving atoms in the six-membered ring, the energies of both conformers could be lowered. As observed by Elmore et al., the cyclohexane ring for the most stable structure of 9 has a twist-boat and for 10 a chair conformation [4].Also after the changes in the geometries of the rings, the isomer with the carbonyl group pointing down, intermediate 10, was lower in energy, with 44.32 kcal/mol for 10 and 54.37 kcal/mol for 9.

The alkene in this compound is particular unreactive, as it is situated at the bridgehead of a bicyclic compound. This characteristic is called “hyperstability” of the alkene and was first described by Schleyer et al. [5]. The specific stability is given by the cage structure of the olefin that is located directly at the bridge-head, and is not due to steric hindrance or enhanced π-bond strength. This effect makes the bicyclic containing the olefin thermodynamically more stable than the parental polycloalkane and hence very unreactive. This can be seen from molecular mechanics (MM2) calculations for product 11. As a test of “hyperstability”, the alkene in intermediate 10 was functionalised by the addition of an OH group (similar to the end structure of Taxol[1]. The resultant product 11 has a higher relative energy of 60.11 kcal/mol compared to 44.32 kcal/mol for the intermediate. Product stability is the key factor in a thermodynamically driven process and explains why the functionalisation of the alkene proceeds so slowly.

Modelling using semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

PART 1

Compound 12 was reproduced in ChemBio 3D and its geometry was calculated first by MM2 and then by MOPAC/PM6 and RM1 Molecular Orbital methods. The models generated by the different energy minimalisation methods differed in the dihedral angles in the two rings, MM2 giving flater angles in the two 6-membered rings (11 and 19°) compared to the MOPAC calculations (16.7 and 29.0°). The bigger angles were observed on the ring which is exo to the chlorine atom for both minimisations. This results also in bringing the alkene exo to the chlorine closer to the bridge-head than the endo (2.493 vs. 2.504A).

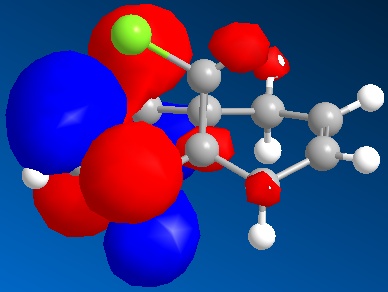

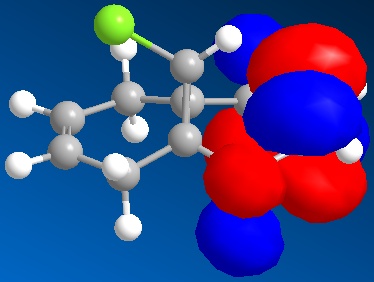

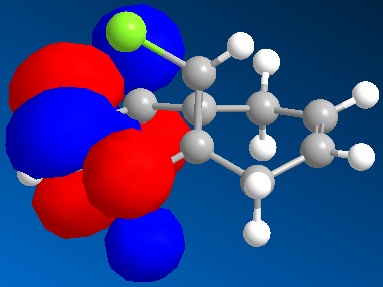

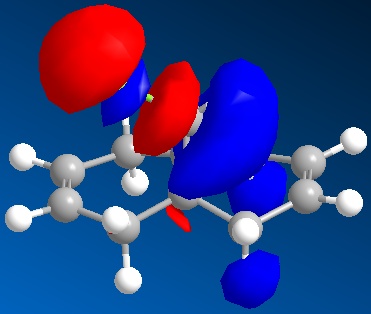

The inclusion of Molecular Orbitals using the MOPAC calculations showed that the two alkenes do not have the same reactivity. The HOMO is situated on the alkene situated on the left ring in the figure, i.e. the ring situated on the same endo to the chlorine. This means that this is the alkene more susceptible to electrophilic attack. MOPAC/RM1 or PM6 methods hence allow us to distinguish between the two alkenes. The reaction with dichlorocarbene would proceed with the more reactive alkene endo to the chlorine atom [6]. This can be explained by the stabilising of the exo alkene by anti-periplanar interactions of the Cl-C σ* orbital (LUMO+2) and the exo-alkene π-orbital (HOMO-1). This also explains the distorted geometry mentioned above. The alkene exo to the chlorine is closer to the bridgehead than the endo alkene because of this anti-periplanar interaction. More importantly for the reactivity, this interaction results in rendering the endo-alkene more Nucleophilic in a frontier orbital and electrostatic sense.

HOMO compound 12  HOMO-1 compound 12 HOMO-1 compound 12

|

LUMO compound 12  | LUMO+1 compound 12 | LUMO+1 compound 12

|

LUMO+2 compound 12

|

PART 2

The models of compound 12 and its hydrogenated version (12hydro), where the exo double bond is replaced by a C-C single bond, were generated on ChemBio 3D and optimised by MOPAC/PM6. The influence of the Cl-C bond on the vibrational frequencies of the molecule were analysed for both compounds. The vibrations were obtained by the density functional approach.

The IR stretches illustrating the difference between the monoene and the diene are summarised in the table below. The IR frequencies obtained are all systematically about 8% too high Mod:organic#Analyzing_the__Vibrational_Spectrum. It can be noticed that there are two C=C stretches for compound 12 and only one for its hydrolised version. These stretches are in the area of about 1750cm-1. Also the very strong symmetric alkene- C-H stretches observed at about 3180cm-1 and the weaker corresponding assymetric stretches at around 3150cm-1 are two for compound 12 and just one for the hydrolised compound as expected. The C-H exo stretches of the alkane are observed for the hydrolised version as very intense peaks. THis can be explained by the antiperiplanar interaction with the C-Cl antibonding orbital.

The C-Cl stretches are observed at around 770cm-1 for both compounds with a similar intensity.

Mini Project

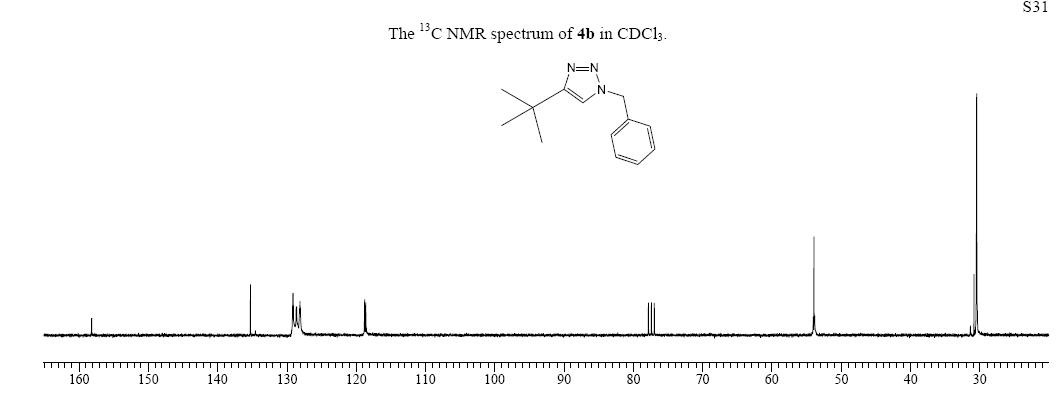

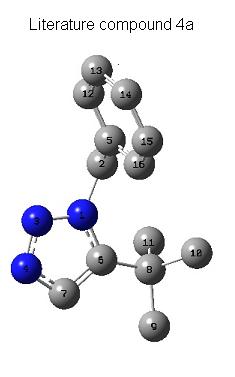

The 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition between a substituted azide and a substituted alkyne to give a 1,2,3-triazole was analysed by molecular mechanics, MOPAC and Gaussian calculations. The reaction can give two different regioisomeric products and under Cu(I) catalysis, the 1,4-isomer predominates . Compound 4a described by literature was modelled on ChemBio 3D and its 13C NMR spectra was calculated. The same was done for its isomer. The data obtained from the 13C NMR spectra was then compared to the data obtained experimentally [7].

The analysis of the 13C NMR spectra generated using the Gaussian method DFT=mpw1pw91, is a very recently developped method of analysis[8].

From the optimised models displayed in this discussion, the 13C NMR spectra were obtained [9]:

13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 28.58(10C), 28.61 (11C), 29.31 (8C), 30.54 (9C), 52.14 (2C), 121.59 (16C), 122.43 (14C), 123.14 (13C), 123.36 (15C), 123.85 (12C), 124.41 (7C), 132.11 (5C), 139.64 (6C)

The values for chemical shifts were compared to the literature values described below:

13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 29.72, 29.99, 52.60, 126.32, 127.68, 128.61, 131.26, 131.37, 136.37, 146.00. [10].

The 13 C NMR spectrum of the isomer of 4a, labelled as 4b was obtained experimentall from the same source:

From the calculated spectrum, the peaks could be assigned to the relevant C atoms. The values at low chemical shifts from about 28 to 53 ppm are consistent with the experimental values for compound 4a and 4b, for higher values, it can be seen that the spectra do not coincide and that there is an error of about 5ppm with the experimental spectrum of 4a, which might be a systematic error. For comaprison, the 12 C spectrum was also computed using the method described above [11].

The IR spectrum was calculated aswell for the compound: [12].

References

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Food and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838 DOI:10.1021/jo00356a016

- ↑ Leleu, Stephane; Papamicael, Cyril; Marsais, Francis; Dupas, Georges; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928.DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ Leleu, Stephane; Papamicael, Cyril; Marsais, Francis; Dupas, Georges; Levacher, Vincent. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928.DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Maier, W.F.; Schleyer, P.v.R., J.Am.Chem.Soc. 1981, 103, 1891-1900DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003 ; and A.B. McEwen, P.v.R. Schleyer, J.Am.Chem.Soc, 1986, 108, 3951-3960 DOI:10.1021/ja00274a016 and for other examples and discussions of hyperstability see A.Greenberg, D.T. Moore and T.D. DuBois, J.Am.Chem.Soc, 1996, 118, 8658-8668 DOI:10.1021/ja960294h

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese and H. S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Li Zhang, Xinguo Chen, Peng Xue, Herman H. Y. Sun, Ian D. Williams, K. Barry Sharpless, Valery V. Fokin, and Guochen Jia; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15998; DOI:10.1021/ja054114s

- ↑ S. D. Rychnovsky, Org. Lett., 2006, 13, 2895-2898. DOI:10.1021/ol0611346 , C. Braddock and H. S. Rzepa, J. Nat. Prod., 2008, 71, 728-730. DOI:10.1021/np0705918 and Goodmans' tools for aiding NMR analysis. See DOI:10.1021/jo900408d

- ↑ Gaussian modelled 13C spectrum of literature compound 4a: Daniel Pohoryles, 2009, DOI:10042/to-2960

- ↑ Additional material of: Li Zhang, Xinguo Chen, Peng Xue, Herman H. Y. Sun, Ian D. Williams, K. Barry Sharpless, Valery V. Fokin, and Guochen Jia; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15998; DOI:10.1021/ja054114s

- ↑ Gaussian modelled 13C spectrum of literature compound 4b: Daniel Pohoryles, 2009, DOI:10042/to-2967

- ↑ Gaussian modelled IR spectrum of literature compound 4a: Daniel Pohoryles, 2009, DOI:10042/to-2965