Mod.1jlm07

Module 1:The Basic Techniques of Molecular Mechanics and Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Methods for Structural and Spectroscopic Evaluations

The molecular properties of various molecules will be studied using computational methods to predict outcomes of reactions, in particular stereo- and regio-selectivity, as well as thermodynamics v's kinetics. Firstly Molecular Mechanics (MM) will be used; this means that no quantum calculations will be calculated and the molecules will not be thought of as wavefunctions but the sum of individiual properties invoked on a given system; bond stretches, bond angle deformations, bond torsions, van der waals repulsions, and electrostatic dipole attractions. The Chem3D programme that will be used is parameterised so that calculations act to optimise characteristics of a molecule towards that known parameter, e.g. geometry, bond angles, total energy, etc. Following this, the Semi-emperical Molecular Orbital Method will be used, which combines the MM method with quantum mechanical studies (treating the molecules as wave functions)to do similar calculations in hope for a more accurate and reliable outcome.

Molecular Dynamics

Dimerisation of Cyclopentadiene followed by Hydrogenation of the Dimer

Diels Alder dimerisation of cyclopentadiene generates 2 potential stereoisomers; one kinetic isomer and one thermodynamic isomer. The most favoured can then be hydrogenated to generate another set of potential stereoisomers, which after prolonged hydrogenation can become a tetrahydroderivative. Using MM2 force field in Chem 3D, the energies of the isomers can be calculated to determine the most favoured isomer, Table 1.

Dimerisation:Comparing the energies of 1 and 2, shows 1 has the lower overall energy. Most of the contributing energies are also lower, the most significant being the torsion angle. Analysing the torsion angles between the new bonds being formed upon the dimerisation reaction, shows the exo form has a dihedral angle of 740, Fig.1, whereas the endo isomer equivalent is 450.

The smaller the angle, the closer the atoms are together and hence the higher the energy of the molecule. Since 1, the exo isomer has the lowest total energy, it is the thermodynamically favoured product. However, it is well known that this diels alder reaction is specific for the endo product. So why is this? The reaction is a balance between thermodynamics and kinetics. In this case, kinetics wins meaning that the stability of the transition state must override the product stability and causes the least stable product to be formed. This is due to better orbital overlap in the transition state of the endo formation compared with that of the exo. [1] This cannot be fully predicted by the MM2 method because it does not consider orbital wavefunctions when making its calculations. Pericyclic reactions are controlled stereoelectronically and hence need to be considered as wavefunctions to make a full, accurate prediction of the stereochemical outcome of the reaction. Using the semi empirical approach begins to attempt this by generating the frontier orbitals, but in this case, only really shows that orbital overlap is favoured rather than determining which isomer is favoured: see Fig.2 and 3.

|

|

Hydrogenation: In this case, the total energy of 3 is higher than that of 4, but it seems there are a few more contributions to this deviation in the energy breakdown. Molecule 4 has a slightly higher torsion strain due to the more "cis" like conformation it is taking, but the van der waals is higher for molecule 3 due to increased 1,4, hydrogen overlap. The most significant difference is the bending energy. This is much higher for molecule 3 and can be analysed by calculating the bond angles about the double bond. Molecule 3 deviates furthest from the ideal sp2 carbon parameterised by Chem 3D to be 1200, at only 1080, Fig.4. In contrast molecule 4 has a more ideal angle of 1130, is closer to the ideal bond angle, and hence has a lower Total Energy. Overall, this predicts the most thermodynaimically stable molecule is 4, and only 3 will be formed if kinetics puts up a good competition. It takes prolonged hydrogenation to acheive the tetrahydroderivative since this is of a similar energy to 3, this time the extra energy contribution coming from torsion strain.

Overall, the most favoured reaction sheme can be shown below:

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue)

The presence of the large aromatic ring can prohibit rotation of a molecule to such a degree that the phenomena of atropisomerism exists. This is the formation of one specific isomer due to lack of rotation about the c-c single bonds due to steric hinderance of the large rings. This is also refered to as axial chirality and is observed in the following pyridinium ring nucleophilic additions to NAD+ analogues.

The prolinol derivative 5 reacts with the grignard MeMgI by co-ordination to the amide carbonyl oxygen. The only product formed is that in which the new methyl group is added pointing above the pyridinium ring. This is due to the nature of the transition state. Molecule 5 can take 2 conformers; the amide carbonyl group can either be co-planar with the pyridinium ring or point anti to the hydrogen on the chiral centre.[2] After running some calculations adjusting the position of the carbonyl group it turns out that the co planar struture is prefered with the lowest energy (43.146Kcal/mol). In fact, the carbonyl group is not quite coo planar but it sits just above the ring at 110. Fig.1. This agrees with the 6 membered ring transition state that would bring the methyl in on top of the pyridinium ring, Fig.2.

|

|

Note that the MeMgI structure could not be included in any calculation itself as the MM2 method is limited; it runs its calculations on summations of non-interacting entities of a molecule rather than wavefunctions therefore it cant account for bond making or breaking. Including two molecules wont run a calculation. Furthermore, the programme itself doesnt have Mg in it, so trying to run a calculation just wont work.

Molecule 7, a similar prolinol derivative, has a similar approach. Again, it can only take two conformations with respect to the carbonyl position. It can either be below the pyridinium ring (1080, 690.820Kcal/mol) or coplanar/slightly above (170, 80.372Kcal.mol). When reacting with the amine PhNH2, again only one stereoisomer is observed. Thinking about this mechanistically explains why; the lone pair on the amine nitrogen attack the pyridinium ring rather than coordinating to the carbonyl oxygen. This means there will be some repulsion between the amine and the carbonyl and the amine will attack from the top side of the molecule,Fig.3.

The product of the Molecule 7 reaction leads to the stereospecific, syn conformation, Molecule 8. The Total Energy of Molecule 8 is lower for the anti conformation as opposed to the favoured syn conformation. As previously discussed, this means the pathway must run kinetically rather than thermodynamically. Again, linking this to mechanisms, transition states stabilities, and atropisomerism (allowed conformations due to physical hinderance), the reason for this is that is steric hinderance about the c-c single bonds due to the presence of the large 7 membered ring, preventing any more stable transition states from forming.

Trying to run calculations of the alternative anti product in Chem3D, automatically reverts back to the original syn conformer. This again is due to the parameterisation of the programme recognising the restricted rotation and essentially disallowing the anti product to be a viable conformer. Therefore, to improve these models and hence allow the energy of the anti conformer to be allowed, ortibal wavefunction calculations can be included rather than just the summations of the non-interacting terms.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

During the multistep synthesis of Taxol, an isomeric intermediate forms. This intermediate is an atropisomer and hence cannot be invertconverted due to steric hiderence. Again, using MM2 calculations in Chem 3D, the energy of the two possible conformers can be minimised to find which is the most stable. This can be achieved by moving the positioning of the carbonyl group that sits in the centre of hindered rotation. The results are shown below:

|

|

|

| Energy | Product | ' | ' |

| 9 | Intermediate | 10 | |

| Stretch | 2.856 | 3.146 | 3.009 |

| Bend | 16.2217 | 19.559 | 19.250 |

| Torsion | 20.086 | 21.610 | 20.397 |

| Non-1,4 VDW | 0.828 | 0.354 | 0.259 |

| 1,4 VDW | 13.990 | 14.880 | 14.832 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.102 | 0.077 | 0.045 |

| Total | 54.483 | 59.937 | 58.068 |

It is clear that intermediate 9, when the carbonyl group is pointing upwards, has the lowest energy. This is about consistant throughout all the energy break downs except for the van der waals and dipole-dipole interactions. The intermediate molecule is of the highest energy and just proves how you must be careful when running the calculations not to fall into local minimums. This meant choosing the carbonyl postion had to be sufficiently adjusted in order to achieve the desired conformation. Furthermore, the energy of the molecule could be reduced futher by adjusting other areas of the molecule. If you rotate the Jmol images attached to the images above, it is clear that the cylohexane ring that makes up part of the molecule is in a twist'boat type conformation. Manually adjusting the carbon atoms so the ring adopts a more chair like structure the energy can be reduced by 12Kcal/Mol to 42Kcal/mol, Fig. 4. Again, roatating the molecule on the Jmol attachment, shows how the H-H interactions have been considerably reduced; they all point as far out as possible, opimising the space and tending towards the desired Csp3 arrangement. This is also reflected in the more significant reduce in the bend (12.016Kcal/mol), torsion (16.069Kcal/mol), Non 1,4, Van der waals (-1.212Kcal/mol), and van der waals (12.135Kcal/mol).

Intermediate 9 is a particular type of alkene known to react slowly; it is a hyperstable alkene. Hyperstable cycloalkenes are more stable than the corresponding cycloalkane. Therefore, hydrogenating the alkene to an alkane leads to a less stable product. Running MM2 on the hydrogenated alkene 9 (i.e. the alkane) gives an increased total energy to 73.645Kcal/mol. The most contributing energies to this are the bend (27.952Kcal/mol) and the Van der waals (17.926Kcal/mol) showing how the molecule undergoes increased torsion strain due to vicinal and transannular hydrogen interactions. Overall, this makes the alkene much less reactive and hence undergoes slow funtionalisations [3]. The increased strain and interactions are clearly visible in Fig. 5.

Semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Regioselective Addition of Dichlorocarbene

|

Molecule 12, Fig.1. undergoes regioselective addition to the double bond anti to the chlorine atom by electrophiles such as dichlorocarbene. To study such a reaction and hence prove this favoured reactivity requires knowledge of the frontier orbitals or the molecule as well as electrostatics. This in turn, requires use of wavefunctions to perform calculations rather than just molecular mechanics as the calculations so far have been. Therefore, a combination of both Molecular Mechanics (MM) and Molecular Orbit Theory (MOT) will be used. MM2 was run to obtain the lowest energy structure of the molecule (MM)(17.901Kcal/mol), followed by MOPAC/PM6 calculation selecting 'molecular surfaces' (MOT). The resulting surfaces of the frontier orbitals are shown in Fig's 2-5.

|

|

|

|

|

The orbitals highlight the differences in the reactivity of the molecule, particularly between the two alkenes. Jlm_distortion.jpg|200px|right|thumb|Fig.7.pi-sigma* interaction stablises molecule 12]] So which alkene is most reactive? The HOMO is the most nucleophilic orbital, therefore the alkene with the most nucleophilic HOMO will be the most reactive. Looking at Fig.2 and 3, the HOMO-1 has a larger coeffient on the endo/anti-alkene pi orbital, making it more sterically accessible than the exo and hence rendering it more susceptible to electrophilic attack. This means the endo, being more electrophilic, will be more susceptible to nucleophilic attack. Furthermore, the endo pi orbital is stablised by interaction with the C-Cl sigma* orbital (LUMO+2) further lower the likelyhood of electrophilc attack here. the interaction of exo pi orbital with the C-Cl sigma*, pulls the chlorine atom towards the ring and causes the ring to bend up slightly. This distortion pushes the cyclopropyl bridgehead carbon away slightly lengthening the distance betwween the two C-C atoms, futher stabilising the molecule, Fig.7. [4]

Moving on to analyse the vibrational energies of the structures can be done in Gaussview. Firstly, the Chembio file was set up to run the density function using the Gaussian interface, B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) basis set and running an 'opt freq' calculation. After sending the .gjf file to Chemscan, the results were collected and the IR spectra obtained for both Molecule 12 and its hydrogenated derivative. The vibrations were observed by animation, showing the displacement vectors, Fig.8, to find the desired vibrational stretching frequencies. The IR spectra were then zoomed in to the appropriate areas to show the C-Cl and C=C stretching frequencies and are shown in Fig.9 and 10.

|

|

Fig. 9 and 10. show that there is a slight shift in frequencies between the vibrations of the two molcules but overall they are quite similar. Molecule 12 has the extra endo alkene vibration at 1737cm-1. Comparing this with the syn stretch at 1758cm-1 shows that the endo C=C bond absorbs at a longer wavelength and hence is a slightly weaker bond. This explains why it is easier and more likely to undergo addition across this bond compared with the syn C=C bond. The minimised energy for this molecule is 22.34Kcal/mol, so is of higher energy than the starting reactants.

It should be noted for the diene that it has a Cs axis of symmetry. This means that the 70 or so vibrations that are possible when running the calculation can be halved since most of them are doubled: the vibrations on one ring are the same as the vibrations in the otehr ring. Specifying this symmetry when sending the calculation off to run, will reduce the calculation time by half.

Structure based Mini project using DFT-based Molecular orbital methods

PtCl2 Catalyzes Cycloisomerisation of 1,6-Enynes for the Synthesis of Substituted Bicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes[5]

1,6 Enynes undergo cycloisomerisation in the presence of a PtCl2 cataylst to synthesis substituted bicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes. This reaction is very solvent, temperature, and substituent dependent i.e. the product that forms varys when run in different solvents, at different temperatures, and as the functional groups attached to the 1, 4 and 9 positions are changed in size and electronegativity. Varying the R group at position 9 is demonstrated in Fig.1[6].

The main effect of varying these parameters is:

- Mechanism of reaction and hence the type of product produced: e.g. 5-exo-dig cyclisation to 1-alkenylcyclopentene isomers, or 6-endo-dig cyclisation to a bicyclo[3.1.0]heptene.

- The percentage of product produced

- The ratio of Z/E isomers produced

For instance, when R=Bn, the reaction in Toluene at room temperature for 12hours, observed no reaction (percentage yield was=0%). Increasing the temperature to 800C for 1 hour, generated a 99% yield of Z/E 2:1 ratio. Switching the solvent from Toluene to Dioxane, decreased the yield to 35%. It is important to note that this reaction is stereoselective and not stereospecific; the reason for this lies behind the mechanism, Fig.2. The 1,6-enyne A, may produce a metal carbene B, which may undergo 1,2-hydride migration to C, which then eliminates the metal fragment to D. Since this runs via a carbocation intermediate, stereochemical information is lost and the production of both stereoisomers is possible.

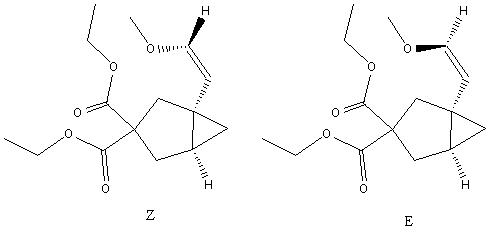

After the reaction conditions were optimised (5mol% PtCl2, in Toluene at 800C) the moleucle that generated a 1:1 ratio of Z:E was when R=Me, Fig.3,4 and 5. 13C NMR data was retrieved on both isomers and hence this is a good molecule to investigate; It is fairly conformationally restricted since it is bicyclic; exists as two isomers; and changing the R group from Bn to Me reduces the number of carbons in the molecule. Overall this makes the molecule suitable for calculations that wont take too long to run and should yield some nice data.

|

|

Geometry Optimisation and NMR Calculations

Before any spectroscopic calculations can be carried out, firstly the energy of the two isomers must be optimised. In Chem3D, the energies were minimised to their lowest possible conformers by manually adjusting the atoms to sit in their most prefered conformation. Since the molecule contains two ester groups, these were adjusted to ensure an antiperiplanar arrangement. After running MM2, the Z isomer optimised at 51.559Kcal/Mol (0.0823a.u), compared with the E isomer at 41.577Kcal/mol(0.0663a.u). To ensure this was the lowest energy state possible, a further geometry optimisation calculation was run on SCAN with the gaussian input file parameters DFT:mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p). This generated optimised energies on gaussview 5 of -960.7314a.u and -960.7130a.u respectively. Note how the energies of these two are very close, hence the thermodynamic favourability to exist in a 1:1 ratio.

|

|

Once optimised, 13C NMR spectra calculations were run for both isomers using the GIAO method, DFT:mpw1pw91/6-31(d,p) NMR scrf (cpcm,solvent=chloroform) on SCAN to produce the following spectra, Fig.6 DOI:10042/to-2932 and 7DOI:10042/to-2933 .The assignment of the carbon responsible for each peak is labelled in Fig.4 and 5. The spectra data was compared to the literature, Table 1.

| Z isomer | ' | ' | E Isomer | ' | ' |

| Calculated | Lit/Exp | Calculated | Lit/Exp | ||

| Carbon | Shift | Shift | carbon | Shift | Shift |

| 9 | 169.6 | 173.0 | 8 | 167.0 | 172.7 |

| 7 | 166.2 | 172.1 | 7 | 166.2 | 172.0 |

| 16 | 141.7 | 146.7 | 13 | 146.2 | 147.3 |

| 15 | 104.8 | 108.6 | 12 | 105.1 | 106.7 |

| 1 | 70.2 | 61.5 | 1 | 69.6 | 61.7 |

| 11 | 61.5 | 61.4 | 10 | ||

| 13 | 61.2 | 59.8 | 19 | 60.5 | 61.6 |

| 18 | 56.9 | 59.6 | 15 | 56.7 | 59.8 |

| 5 | 45.4 | 5 | 45.5 | 56.2 | |

| 2 | 40.5 | 40.6 | 2 | 43.6 | 39.9 |

| 4 | 34.2 | 36.0 | 4 | 34.4 | 35.9 |

| 6 | 32.0 | 27.2 | 3 | 31.4 | 26.4 |

| 3 | 30.4 | 25.2 | 6 | 27.8 | 26.0 |

| 12 | 14.5 | 17.1 | 11 | 15.9 | 15.6 |

| 14 | 14.4 | 14.0 | 20 | 15.5 | 13.7 |

From the graphs, it is clear that there are shifts in the peaks between different isomers. The shifts observed between 166-169ppm correspond to C8 and C9 (Z) and C8 and C7 (E). These in turn correspond to the carbonyl carbon on the ester groups. These appear at similar chemical shifts in both isomers but are closer together in the E isomer. C15 (Z) and C18 (E) correspond to the OMe Carbon at the isomeric site. Again, they appear at very similar chemical shifts (~56.8ppm) but have a slightly different relationship to C13 (Z) and C19 (E) of (CO2CH2CH3), the ethyl group next to the ester . In the Z isomer, they are very close together relative to the E isomer. Finally, C16 (Z) and C13 (E) relate to the point of isomeric distinction; the carbon next to the OMe group on the double bond. Between the two isomers there is a shift of approximately 4ppm clearly identifying between the two isomers.

It is also clear there are some deviations between the calculated values and those experimentally observed. To test the deviation it was important to notice there is an error in newly published literature (only currently published on the web) having only 14 peaks, when the molecule actually contains 15 Carbons. Since it is essential to have the same number of data points to run error analysis, eliminating a value had to be carried out. Logically, the most anomolous value was removed to best fit the data. It must further be noted, I can not be sure if this was a typo error in the literature itself or because the wrong molecule was assigned altogether. Since the agreement with the calculated values is fairly good, this leads to the conclusion that it was just a typo. Further reason for error is due to the presence of the ester groups; the calculations are not accurate when assigning these and hence lead to deviation. Running error calculations on these shows that the fit is fairly accurate, Table 2.

| Isomer | Deviation From Lit Value | ' | ' |

| MAE | CMAE | CP3 | |

| Z | -0.3 | -0.6 | -0.23 |

| E | -0.7 | -1.3 | -0.23 |

These errors correspond to the Mean Absolute error, MAE; the corrected mean absolute error, CMAE; and CP3. All these methods look at the differences between the experimentally observed NMR signals and the computational calculated ones to see how closely related they are and hence determine which isomer corresponds to which graph. The equations used to calculate the errors are shown in Fig.8[7]. The Graph generated in the CMAE calculation is also shown in Fig.9.

|

This concludes the calculated assignment matches the experimentally observed data within good accuracy, particularly for the more favoured conformation, the Z isomer.

J H-H Coupling

Further information can be taken from the optimised geometry of the two isomers. Using Chem3D, the dihedral angles between the protons either side of the double bond in question can be calculated and using Karplus equation the expected Jvalues calculated. Since i am looking at an sp2 rather than sp3 carbon, the suggested calculation methods can not be used. Instead, the Karplus graph will be employed, Fig.10.[8]

The angle calculated for my Z isomer was -0.850 and that of the E isomer was 179.250. Therefore, the expected coupling constants would be approximately 11Hz and 13Hz respectively.

IR Spectra Predictions

Since the molecule only has 15 Carbon atoms in it, it is possible to run the vibrational frequencies within a reasonable time. The # b31yp/6-31(d,p) opt freq calculation was run and the following Free Energies obtained from the Output File

- Z isomer: Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -960.656 a.u

- E isomer: Sum of electronic and thermal free energies = -960.636 a.u

The Z isomer lies slightly lower in energy but they are both very close; the difference between these two isomers is 0.020 a.u.(1.26Kcal/mol.

The IR spectra generated can be compared below in Fig.11 and 12.

After comparing the animations of the specific vibrations for the two isomers, the following (more significant) differences in frequencies due to the change about the double bond is tabulated in Table 3.

| Vibrational Group | Frequency/cm-1 | ' |

| Z | E | |

| OMe + H adj to Ome | 1152.77 | 1166.45 |

| H adj to Ome | 1294.24 | 1290.95 |

| H\'s across C=C bond | 1320.38 | 1329.14 |

| Ome | 1498.19 | 1491.28 |

| C=C | 1747.99 | 1749.57 |

| Ome | 3006.91 | 3007.24 |

This shows how the energies of vibrations of the different isomers do vary and hence can be used to distinguish between the two. The difference between the C=C bond is quite small, but that of the OMe bonds is quite large, with a maximum difference of ~8cm-1. This suggests examination of the vibrations in the group that is moving cis to trans can determine the difference between the two isomers. The Z isomer vibrates at a shorter wavelength and hence is the stronger/more stable bond.

Optical Rotation

Since the Molecule has two chiral centres the optical rotation calculation can be run to see how it rotates polarised light. A # b31yp/aug-cc-pvdz polar(optrot) scrf(IEFPCM,solvent=chloroform) CPHF=RdRdFreq at 589nm was run as well as aug-cc-pvdz=6-31G(d,p). The latter was returned as finished but did not actually give an optical rotation result. This suggests that, since the chiral centers where making up a cyclopropane ring and a cyclopentane ring, there is too much rigidity within the molecule to be able to rotate.

Circular Dichroism (CD/UV-VIS) Spectra

Finally, a # b31yp/aug-cc-pvdz td(Nstates=20) scrf(IEFPCM,solvent=chloroform) was run to get a CD and UV/Vis spectrum for each isomer. In a similar agrument for the optical rotation, the CD did not come out; if plane ploarised light cannot be rotated, neither can circular polarised light. The UV VIS is shown below in Fig.13 and 14.

|

|

It appears here are more absorptions/transitions seen in Z isomer compared to E isomer, suggesting the electrons are in slightly different energy states. The Z isomer must be allowing more transitions and vibronic coupling to occur, perhaps entering more singlet and triplet states, than the E isomer. The more intense absorption peaks are 211nm (Z) and 215nm (E). This shift in frequency for absorption also suggests Z is more easily excited as its max absorption lies at a lower energy of vibration.

Conclusions

For smaller and more rigid molecules, it seems these calculations work to quite a good degree of accuracy. All the methods allow the differentiation between the isomers; NMR, IR, and UV, all showing shifts in the ppm, frequency, and wavelengths, respectively.Minimising the energy using MM2 is sensitive to falling into local minima and needs to be tested a few times to find the conformation of the lowest energy. Sometimes, this means manually altering the positions of the atoms to their optimum position to try to do this; this can be quite tedious at times if the local minima and global minima are close in energy. Other that this, it is also a good way to approach lowering the molecular energy. However, once you deviate from these more rigid, simple molecules and move towards molecules with more flexibility, the number or rotations and conformations possible increase and hence the accuracy of the calculations decays. Furthermore, it works better for known molecules (and the groups making up the molecules), since it relies on set parameters from known conformations e.g. ethyl esters are lowest in energy when arranged antiperiplanar, sp2 carbon centres have prefered angles of 1200. The Optical Rotation and CD calculations were quite unsuccessful, taking quite a long time to run and seeming to fail once completed. Even when changing the basis set from aug type to 6-31G in an attempt to speed up the simulation, it still took a very look time and ultimately came out with a fail. Overall, lots of information can be determined from running these calculations and determination of isomeric conformations is achievable.

References

- ↑ Claydon, Greeves, Warren, and Wothers, Organic Chemistry, 2001, p.905-922

- ↑ A. G. Shultz, L. Flood and J. P. Springer, J. Org. Chemistry, 1986, 51, 838.

- ↑ Tetrahedron. Vol. 53, No. 28, pp. 9727-9734. 1997

- ↑ J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2, 1992, 447 - 448

- ↑ Liu Ye, Quian Chen, Jiancum Zhang, and Veronique Michelet, J. Org. Chem,(As Soon As Publishable), Web publication: Nov 19th 2009

- ↑ Liu Ye, Quian Chen, Jiancum Zhang, and Veronique Michelet, J. Org. Chem,(As Soon As Publishable), Web publication: Nov 19th 2009

- ↑ J. Org. Chem., 2009, 74 (12), pp 4597–4607

- ↑ http://www.cem.msu.edu/~reusch/VirtualText/Spectrpy/nmr/nmr2.htm