MRD:js5515physcomp

Molecular Reaction Dynamics

Exercise 1: H + H2 system

Question A

What value does the total gradient of the potential energy surface have at a minimum and at a transition structure? Briefly explain how minima and transition structures can be distinguished using the curvature of the potential energy surface?

The total gradient of a potential energy surface has total gradient equal to zero at both a minimum and a transition state. A minimum is a stationary point on the potential energy surface where the first derivative is equal to 0 in all directions. The transition structure lies on the saddle point at the “center” of the saddle-shaped region of a theoretically calculated PES. It is also a stationary point (zero first derivative). Minima and transition structures do however differ mathematically, a saddle point (transition structure) is a maximum along the reaction coordinate and minimum in all other directions, whereas a minimum is a minimum in all directions. Minima and transition structures (saddle points) can be distinguished by their second derivatives, [1].

For a minimum in all directions (q);

For a transition state in all (q);

Except along the reaction coordinate, where;

[2].

Nf710 (talk) 16:19, 26 May 2017 (BST) You get the reaction coordinate by correct linearly combining the starting coordinates, this is called taking the normal modes.

Question B

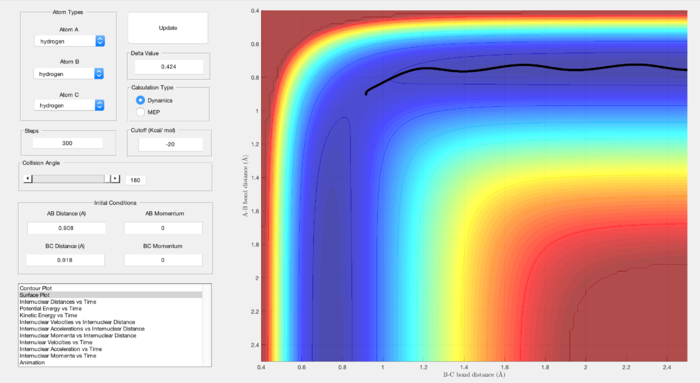

Report your best estimate of the transition state position r(TS) and explain your reasoning illustrating it with a “Internuclear Distances vs Time” screenshot for a relevant trajectory?

The transition state is found at the saddle point on the PES by looking at the maximum on the minimum energy path when the internuclear distances to equal, r1 = r2, and the initial momenta, p, is set to zero. It was calculated to be at -98.8 kcal mol1

After finding the point at which the internuclear distances are equal, a internuclear distance vs time plot was taken (r1 = r2 = 0.908A). This plot showed no oscillation or change in bond lengths and is representative of the transition state as the potential energy is at a maximum and there is no further movement when momentum is zero.

Question C

Set the initial conditions such that the system is slightly displaced from the transition state and zero initial momenta (i.e. the positions r1 = r(TS)+0.01, r2 = r(TS) and the momenta p1 = p2 = 0, then change the calculation type from dynamics to MEP.

Repeat the calculation with the same initial conditions used to calculate the reaction path, but change the calculation type back to Dynamics.

Comment on how the mep and the trajectory you just calculated differ

Conditions used:

r1 = rts+δ, r2 = rts, δ = 0.1

Both the MEP and molecular dynamics plots follow the minima of the valley towards the products. As can be seen in Figure 4, the MEP plot does not provide any information about the motion of the atoms during the reaction. The oscillating curve that can be seen from the Molecular Dynamics plot in Figure 5 shows the vibrations as the respective distances r1 and r2 differ.

The differing appearance in these graphs is due to the MEP plot neglecting the vibrational energy of the molecules and reporting only the minimum energy. They are based on the the curvature and length of the reaction pathway i.e. the intrinsic reaction coordinates. The Molecular Dynamics plot shows how the vibrational energies change as the distances r1 and r2 differ.

Question D

Determine if the following trajectories are reactive or unreactive using the given set of initial conditions.

Using the initial positions r1 = 0.74Å and r2 = 2.0Å, the following momenta combinations were used and the resulting plots were used to determine if the trajectories were reactive or unreactive.

| Trajectory Number | p1 | p2 | Outcome of Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1.25 | -2.5 | reactive |

| 2 | -1.5 | -2.0 | unreactive |

| 3 | -1.5 | -2.5 | reactive |

| 4 | -2.5 | -5.0 | unreactive |

| 5 | -2.5 | -5.2 | reactive |

Trajectory 1:

As can be seen by Figure 6 below, this trajectory is reactive and the momenta used give enough energy for the transition state barrier to be overcome. It passes through the saddle point on the PES (the transition structure) and proceeds to the products. The entrance channel of the PES shows the vibrations of the starting molecule, BC, whereas the exit channel shows the AB product molecule vibrations. Over the course of the reaction, r1 decreases and r2 increases.

Trajectory 2:

Comparing Figures 6 and 8, it can be seen that this trajectory is unreactive. As hydrogen A approaches H2 molecule BC, the AB bond distance decreases but reaches a point at which it bounces back, failing to surmount the energy barrier at the transition state, failing to form molecule AB. Looking at the conditions used, it can be assumed that the momentum is not large enough to overcome the energy barrier.

Figure 9 shows the BC bond distance remaining fairly constant with only small oscillations due to the oscillations within the molecule. The A-B distances decreases to a minimum before reaching the transition state and therefore 'bouncing off'.

Trajectory 3:

Trajectory 3 is very similar to trajectory 1. Figure 10 shows a reactive trajectory, with molecule AB formed. The increased p1 to -1.5 causes greater oscillations in the molecules.

Trajectory 4:

The trajectory is slightly more interesting. Figure 12 shows that this trajectory finishes as unreactive however, there is barrier recrossing. The system surmounts the transition state barrier, forming molecule AB, before recrossing and reverting back to reactants (A + BC).

Trajectory 5:

This trajectory is another example of barrier recrossing however, as can be seen in Figure 14, this trajectory finishes reactively. The system crosses the transition state barrier to form AB + C from A + BC. From here the products revert back to reactants (recrossing the barrier) before converting (crossing the barrier again) back to products (AB + C).

Question E

State what are the main assumptions of Transition State Theory. Given the results you have obtained, how will Transition State Theory predictions for reaction rate values compare with experimental values?

Transition state theory, TST, is based on the understanding that reactants and activated complexes are in quasi-equilibrium and form products up crossing the the saddle point (TS) of a reaction PES.

TST makes a number of assumptions and therefore has limitations. TST assumes that atoms behave according to classical mechanics and so can only react if atoms collide with sufficient energy, and in the correct orientation/position. Quantum mechanics however states that there is finite probability atoms can tunnel through the energy barrier to react and form product molecules, even if they have not collided with sufficient energy. A smaller transition state barrier increases the probability of tunnelling and so TST breaks down for smaller energy barriers.

TST also assumes that trajectories cross the transition state barrier and stay there. This is not in fact the case, as in some cases trajectories do indeed recross the barrier to find the thermal equilibrium as either products or reactant. Further to this, TST makes assumptions about the lifetime of the intermediates themselves. It is assumed the lifetime of each intermediate is long enough to reach the the Boltzmann distribution of energies before the reaction proceeds to the products. TST failed for some elementary reactions as the intermediates are short lived. In multistep reactions, each elementary reactions can have transition states with varying lifetimes and so the theoretical values will not match those determined experimentally.

Alternative reaction pathways around the saddle point are also possible, especially at higher temperatures. TST assumes that the reaction always travels through the lowest energy saddle point on the PES. At higher temperatures collisions are more complicated to model as transitions states are formed that do not sit on the lowest energy saddle points. This is due to the fact that higher vibrational modes are populated and so the TST breaks down. Different values would be seen if tested experimentally as the reaction could travel through different activated complexes.

Nf710 (talk) 16:23, 26 May 2017 (BST) Excellent understanding of TST theory.

Exercise 2: F-H-H system

Question A

Classify the F + H2 F and H + HF reactions according to their energetics (endothermic or exothermic). How does this relate to the bond strength of the chemical species involved?

F + H2 -> HF + H

As can be seen by Figure 13, this reaction is exothermic. The PES shows the products have a lower potential energy than the reactants and the reaction is therefore exothermic. The reaction proceeds by surmounting the transition state energy barrier, energy is lost to the surroundings as heat when the reactants (HF + H) are converted to the lower energy products.

HF + H -> F + H2

As is to be expected, this reaction is endothermic. Figure 14 shows the products at a higher potential energy than the reactants.

The energetics of the reactions can be used to gain information on the relative bond strengths of the molecules. The exothermic reaction to form HF + H suggests that that the H-F bond is stronger than that of the H-H bond as energy is released upon its formation. This is supported by literature values for the respective bond enthalpies.

| Bond | Enthalpy / kJ mol-1 |

|---|---|

| H-H | 432 |

| H-F | 565 |

Question B

Locate the approximate position of the transition state.

According to Hammond's postulate, the transition state of a reaction resembles either the products or reactants of whichever it is closer to in energy. For the forward, exothermic, reaction, the transition state is closer in energy to the reactants and therefore bares further resemblance to the starting molecules/atoms. Oppositely, for the backwards, exothermic, reaction, the transition state is closer in energy to the products and so according to Hammond's postulate, bares more resemblance to the products. [4]

Bearing this in mind, the transition state was located in a similar manner to that of Question 1) b). Figure 15 shows the PES plot with the location of the transition state labelled.

The position of the transition state was found at H-H = 0.74Å and H--F = 1.81Å, Figure 16 shows that this is the approximate maximum potential energy (transition state) as there is very minimal oscillation.

Question C

Report the activation energy for both reactions.

In order to find the activation energy for the reactions, a reactivity trajectory was found using informed trial and error.

For the exothermic forward reaction, F + H2 -> HF + H, the potential energy difference between the transition state and the reactants was inspected. From Figure 17, the energy of the transition state was found to be 24.69 kcal mol-1 and from figure 16, the energy of the reactants was found to be 24.71 kcal mol-1. This corresponds to an activation energy of +0.02 kcal mol-1.

Using the same process, as can be seen in Figure 18 the energy of the reactants in the backwards reaction HF + H -> F + H2 were found to be 31.64 kcal mol-1. A calculated activation energy of +6.96 kcal mol-1 was found and the larger gap is in keeping with the fact that this reaction is endothermic.

Question D

In light of the fact that energy is conserved, discuss the mechanism of release of the reaction energy. How could this be confirmed experimentally?

The law of the conservation of energy states that energy cannot be created or destroyed and thus during a reaction collision the energy change is between potential and kinetic energy. Looking at the PES it is clear that in the forward reaction, the reactants are higher energy than the products and therefore the energy is in the form of PE, the reaction proceeds via an energetic mechanism and the energy is converted to translational and vibrational energy. Figure 18 clearly shows that the vibrational energy is increased in the products (shown by the increase in oscillations of the line after the transition state barrier is overcome)

IR spectroscopy can be used to experimentally confirm this interplay between energy modes, the products will have greater vibrational energy than the products. It could also be confirmed using a calorimeter to measure the heat produced during the reaction.

Nf710 (talk) 16:27, 26 May 2017 (BST) the vibrations will decays and this will be given out as heat.

Question E

Discuss how the distribution of energy between different modes (translation and vibration) affect the efficiency of the reaction, and how this is influenced by the position of the transition state.

For a collision to become a reaction the collision must have enough energy to surmount the transition state barrier and also have a trajectory that crosses the barrier without returning to the reactants. As preciously mentioned, the position of the transition state is dependent on the type of reaction. For an exothermic reaction, the transition state lies nearer the reactants and so the most efficient trajectories are high in translational (rather than vibrational energy). For trajectories of this kind, once past the transition state, they roll from side to side of the product valley and lead to vibrationally excited products.

Conversely, an endothermic reaction has a later transition state that resembles the products. In this instance, reactants with high translational energy are likely to 'bounce off' the surface and back into the valley, remaining as reactants. For reactions of this kind to get around the corner to the transition state, vibrational motion (side-to-side) is needed. Products from these reactions are high in translational energy. [5]

Nf710 (talk) 16:30, 26 May 2017 (BST) Good understanding of polyanis rulesbut you should have proved them with some examples here. Otherwise this is a very nicely written report.

References

<references>

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Liu, J.Q., 1989. A generalized saddle point theorem. Journal of differential equations, 82(2), pp.372-385.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lewars, E., 2003. The concept of the potential energy surface. Computational Chemistry: Introduction to the Theory and Applications of Molecular and Quantum Mechanics, pp.9-41.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Huheey, J.E. and Cottrell, T.L., 1958. The Strengths of Chemical Bonds. Butterworths, London.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Farcasiu, D., 1975. The use and misuse of the Hammond postulate. J. Chem. Educ, 52(2), p.76.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Atkins, P. and De Paula, J., 2011. Physical chemistry for the life sciences. Oxford University Press, USA p.523.