MRD:fr216

Molecular Reaction Dynamics

Abstract

Chemical reactions are often caused by collisions between particles, but not all collisions lead to a chemical reaction. The following calculations have the aim of explaining this statement via the analysis of energy barriers, trajectories and vibrational modes of the reactants involved.

The triatomic system

The system taken in consideration is a triatomic system where a first atom hits a vibrating diatomic.

Exercise 1: H+H2

The initial conditions set for the predicted collision of an H atom (A atom) with a H2 (BC) molecule were rBC = 0.74 Å; rAB = 2.30 Å; pBC = 0.00; pAB = -2.7, and the potential curve obtained from the calculations is shown in figure 2.

Critical points

Answer to question 1

Both reactants and products are minimum energy structures (stable) in the reaction path. This implies that they are going to be located at the two relative minima of the potential energy curve. The relative minima are found by differentiating the potential energy expression with respect to rAB or rBC:[1]

If both derivatives are zero at the same time then the point is known as a critical point. Critical points can either be local minima or maxima or saddle points. The transition state is by definition the saddle point of the potential curve, which means that both partial derivatives need to be equal to zero so that if the equilibrium is moved slightly from the transition state, the geometry will tend towards the reactant or products. From a mathematical point of view:

Where z is the potential curve equation, and x and y are the critical points.If ∆>0 then the point is a saddle point, while if ∆<0 then the point is a local minimum.[1]

The coordinates of the minima points are: rBC= rAB = 0.75 Å

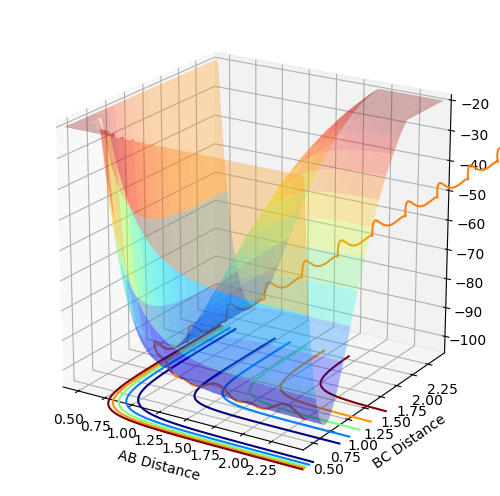

In figures 3, 4 and 5 are highlighted the minima points and the transition state on the potential curve.

|

|

|

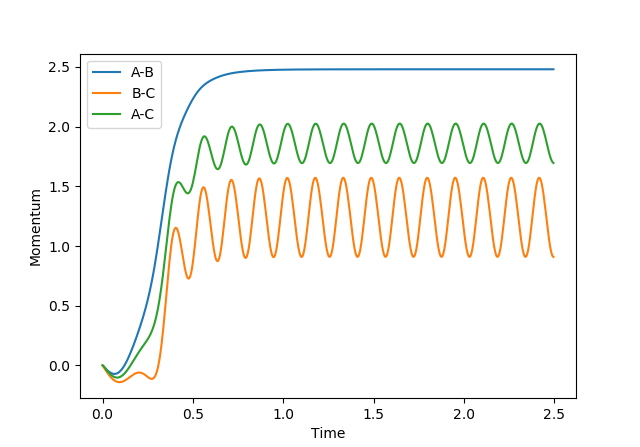

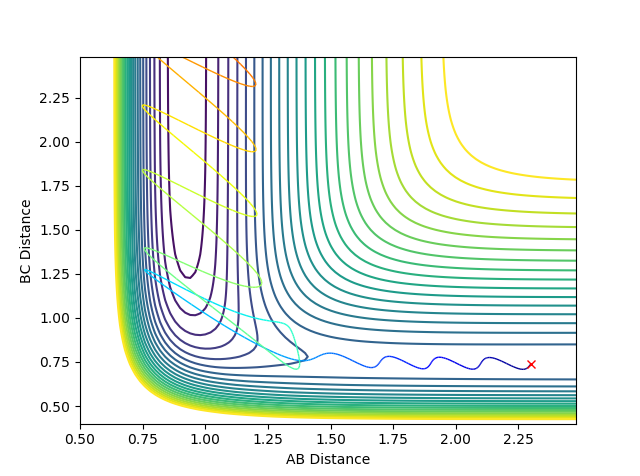

By looking at the distance vs time and momentum vs time graphs we can obtain a rough estimate of the transition state structure. This is because, the transition state is going to be an intermediate structure between AB and BC (crossing point in figure 6) where the overall momentum is zero (no oscillation) (figure 7).

|

|

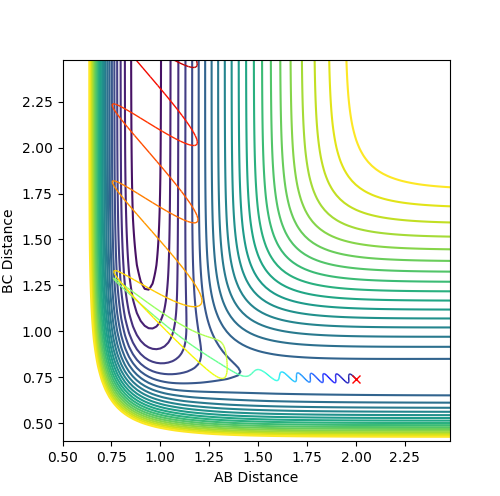

Being symmetric, the transition state must also have rBC= rAB, and by applying these constraints to the potential well and by giving a momentum of zero to all the particles, we can force the trajectory of the collision to oscillate around the transition state geometry. The point at which the oscillation will not occur (figures 8 and 9) is therefore the transition state.

|

|

Answer to question 2:

The value of rBC= rAB found at the transition state was of 0.908 Å.

Ng611 (talk) 13:28, 8 May 2018 (BST) Good explanation!

Reaction path and Trajectories

Answer to question 3:

The MEP graph gives the lowest energy path for the reaction to occur (by following the gradient of the curve) but does not take in account the vibrations of the molecules, while the dynamic analysis takes in account both vibrations and curvature. The following figures are obtained by forcing a small displacement in one of the distances (rAB=0.918; rBC=0.908) at momentum zero, meaning there is a small variation from the transition state.

|

|

A particular note can be made on the Momenta vs time graphs (figures 12 and 13), as it clearly shows that the MEP simulation is not momentum dependent.

|

|

- By applying the same conditions but with inverse initial coordinates for AB and BC, we observe the exact same trends but instead of forming the AB bond, the BC bond is formed.

- By making the initial positions correspond to the final position of the previous trajectory (rAB = 9.0; rBC= 0.74) but with inverse momenta (AB momentum = -2.4; BC momentum = -0.9) we observe the inverse trajectory and formation of the transition state (figure 14).

Reactive and unreactive trajectories

Answer to question 4:

So far we have looked at particular conditions that allow the reaction to go from products to a transition state to reactants, but this is not always the case. By simply changing the values of the momentum we observe that some of the trajectories obtained might not be reactive. The initial distances taken in account for all the examples are: rBC = 0.74 and rAB = 2.0. The trajectories in the following table were explained with the help of the "animation" setting in the program.

Transition state theory (TST)

Transition State theory (TST)[2] can be explained by taking in account the following assumptions:

- The activated complex is in equilibrium with the reactants and not the products

- The reactant nuclei behave according to classical mechanics

- The reaction system passes through the lowest energy saddle point/transition state on the potential energy surface and the reaction rates can be studied by observing the structure at the transition state

This implies that the TST does not take in account the possibility for the activation barrier to be crossed again, like in the case of the fourth and fifth examples of the above table, and does not consider bond vibrations. This unrealistic picture excludes many paths that the reaction could follow, giving a reaction rate which is higher than the experimental values[3].

Ng611 (talk) 13:29, 8 May 2018 (BST) Very efficient discussion. Well done.

Exercise 2: F - H - H

Answer to question 5:

The reaction taken in account is the equilibrium. The forward reaction is exothermic (energy is released into the surroundings), while the backward one is endothermic.[4]

The reasoning for this can be explained by looking at bond enthalpies of formation. F is the most electronegative atom of the periodic table and its difference in electronegativity with H is great. This gives the bond a high ionic character and a very high bond strength. Its bond enthalphy is +569 kJ/mol. The H-H bond is totally covalent and its bond enthalphy is around +436 kJ. Therefore, the energy lost from breaking the H2 molecule is not enough to compensate for the formation of H-F and overall energy will be freed into the system. For the same reasons, the backwards reaction is endothermic.

Transition state and activation energy

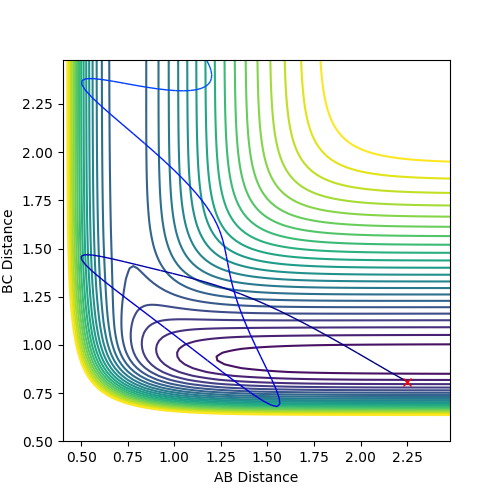

The transition state can be approximated in the same way as before by substituting one of the hydrogens (atom A) with a fluorine atom and applying any conditions that give a reactive pathway (in our case, rAB= 2.3; rBC= 0.74, AB momentum= -2.5; BC momentum= -1.5).

Answer to question 6:

The transition state exact distances can be obtained in several ways. First of all, it is known to be the saddle point of the potential surface graph of a reactive pathway. Secondly, it is also a state whose geometry is a structure in between the one of the products and reactants where the momentum is zero, so by looking at figures 16, 17 and 18 we can get a rough range of distances.

The exact bond distances were then found to be: rAB (FH)= 1.81 and rBC (HH)= 0.74. They were confirmed by looking at both contour plot and inter-nuclear distance vs time graph at momentum zero with the distances of the values above.

|

|

Ng611 (talk) 13:31, 8 May 2018 (BST) The lines in the distance--time graph aren't completely flat -- you're close but I think still a little way off from the true TS.

Answer to question 7:

The activation energy is by definition the difference in energy between the reactants and the transition state energy. The Hammond Postulate[5] states that the transition state is going to resemble in structure the species which is closer in energy. In the absence of a stable intermediate, for an exothermic reaction the transitions state is going to be more similar in structure to the reactants and for an endothermic reaction it is going to resemble the product structure.

The H + HF and F + H2 reactions are both represented by the same potential curve and have the same transition state with energy -103.763. Therefore, It is possible to find the energy of the reactants by forcing a small displacement of the transition state so that the structure falls into the minimum of the reactant or product in the potential curve.

- By displacing rAB of +0.10 and keeping BC constant it is possible to find the activation energy for the F + H2 reaction. A MEP simulation of a contour map was simulated and as expected the transition state fell into the reactant mininum of the potential well. The energy of the reactants was found to be -103.936, which gave an activation energy of 0.173.

- By displacing rAB of -0.50 and keeping BC constant it is possible to find the activation energy for the H + HF reaction. A MEP simulation of a contour map was simulated and as expected the transition state fell into the reactant mininum of the potential well. The energy of the reactants was found to be -133.99, which gave an activation energy of 30.227.

Reaction Dynamics and the Polanyi Rules

Answer to question 8:

An example of reactive pathway is shown in figure 25. At the initial conditions, F and H2 have a certain kinetic energy that allows them to move towards each other and collide. At collision, the transition state is formed and has zero momentum and hence zero kinetic energy. The conservation of energy principle states that the total energy (sum of kinetic and potential) has to be constant. Therefore, all the energy in the transition state has to be potential. Once the transition state is broken down, of of the hydrogen atoms bounces away with a certain kinetic energy and the new HF molecule stays stationary. Its residual kinetic energy goes in bonds vibration and eventually lost to the environment (exothermic reaction). Experimentally this could be confirmed by measuring the change in temperature as the reaction is performed. Being an exothermic reaction, the temperature will increase until the product is obtained.

The Polanyi rules[6][7] state that the vibrational energy is more efficient in promoting a late-barrier reaction than the transitional energy. This implies that if the the reaction is endothermic (late transition state which resembles the product) than the vibrational energy will be the form of energy driving the reaction and the reverse is true for exothermic reactions. The reaction in analysis in the following figures is F + H2, which is exothermic and has an early transition state. In all figures the AB and BC (2.0 and 0.74) distances remain constant with the AB momentum (-0.5) and the BC momentum varies from -3 to +3. By varying the momentum we are giving different amounts of vibrational/translational energy to the system. In figure 26 the H2 molecule has a lot of vibrational energy when it reaches the transition state. The reaction is exothermic and, according to the Polanyi rules, it is not favored by these conditions. As proof of this statement, the reaction resulted to be unreactive. In figure 27 the molecule does not have enough energy to reach the transition state, but in figure 28 it has the right energy to give a reactive trajectory. The vibrational energy put in the system is less (more translation than vibration) and the exothermic reaction is favored (early transition state).

|

|

|

Figure 29 shows a reactive trajectory where the initial BC vibrational energy is very low (mostly translational) and the exothermic reaction is favoured.

The reverse reaction H-F has a very high activation energy barrier due to the strength of the HF bond. This means that the incoming atom H needs to have a very high momentum to make the trajectory reactive.

By setting: F-Atom C, H-Atom B and H-Atom C, the following figure 30 was obtained.

Ng611 (talk) 13:34, 8 May 2018 (BST) Good discussion.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 R.L. Jacobs, Mathematics and Physics for Chemists 1 notes, Imperial College London, 2016.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version:(2006–) "transition state theory".

- ↑ Golden DM. Experimental and theoretical examples of the value and limitations of transition state theory. The Journal of physical chemistry. 1979;83(1): 108-113.

- ↑ Jun Chen ZS, Dong H. Z. An accurate potential energy surface for the F + H2 → HF + H reaction by the coupled-cluster method. THE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS. 2015;142.

- ↑ Hammond, G. S. (1955). "A Correlation of Reaction Rates". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77: 334–338. doi:10.1021/ja01607a027. Solomons, T.W. Graham & Fryhle, Craig B. (2004). Organic Chemistry (8th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-41799-8. Loudon, G. Marc. "Organic Chemistry" 4th ed. 2005.

- ↑ Polanyi JC. Concepts in reaction dynamics. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1972;5(5): 161-168.

- ↑ Zhang Z, Zhou Y, Zhang DH, Czakó G, Bowman JM. Theoretical Study of the Validity of the Polanyi Rules for the Late-Barrier Cl + CHD3 Reaction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 2012;3(23): 3416-3419.