MRD: Reaction Dynamics Report - Benjamin Tapolczay (01048050)

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) Overall a really good job. Well done!)

H + H2 System

Transition State Reaction Dynamics

The Transition State of a reaction can be located on the surface potential energy diagram as the highest energy point on the minimum energy pathway. Consequently, since the minimum energy pathway configurations of H1-H2 + H3 and H1 + H2-H3 either side of this point are lower in energy, the Transition State represents a saddle point on the surface plot. Movement along the internuclear distance axis suggests a local maximum, whereas on viewing the energy pathway, a local minimum is observed. In contrast, the minima on the potential energy surface is confirmed as the lowest energy configuration of the system. In both cases, the first derivative, ∂V(ri)/∂ri, is equal to 0. In order to determine the saddle point of the system, it is therefore necessary to use the discriminant of the 2nd derivative:

where coordinates (a, b) refer to the critical point discussed, and f describes the derivative with respect to the axes labelled in subscript. If D(a, b) < 0, then the coordinates represent a saddle point; if D(a, b) and fxx are both positive, then the coordinates represent an energy minimum.

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) Good use of the second derivative test, but remember that both reactants and products are minima: the definition does not depend on the absolute energy of the system at that point.)

Locating the Transition State

The position of the Transition State in a symmetric reaction system can be identified as the point where the distance H1-H2 is equal to that of H2-H3. By equating the two distances and giving the atoms a momentum of 0, calculations can be run to find the point at which there is no molecular vibration, since the atoms are held in perfect symmetry at the critical point. For this system, the transition state was located at an atomic distance of 0.90775 Å or 0.908 Å (3 s.f.), with the internuclear distance as a function of time shown below in Figure 1. However, the presence of a very slight vibration suggests that the actual transition state has not been reached. It is important to note that the transition state does not actually exist as a specific coordinate, since the use of probabilities and therefore ranges in the mathematical techniques used make it impossible to pinpoint a specific value (the probability of a specific value occurring in a probability density function is always 0, and so a range is taken instead).

The confirmation of this inaccuracy can be seen in the kinetic energy plot of the Transition State, shown in Figure 2. Ideally, at this position the system would have no kinetic energy, as the atoms are held in one orientation and there is no movement, shown by the constant internuclear distance. However, in the calculation run on the predicted transition state, a kinetic energy oscillating between 0 and around 2.25 x 10-8 kcal/mol was observed, again highlighting the fact that the transition state has not been reached.

Calculating the Reaction Pathway

Minimum Energy Pathway Calculation

The Minimum Energy Pathway, or mep, is a stepwise calculation which follows the trajectory of the lowest energy system configuration at different distances, represented by the valley of the surface contour plot. At each step of the calculation, the velocity and therefore kinetic energy of the atoms in the system are reset to zero, and the geometry of the atoms is then optimised to that with the lowest potential energy. The distances between the atoms are then changed, the velocity is reset and the system is reoptimised to a new configuration. At each step, the system looks for the pathway which has the steepest (downward) gradient in order to ensure it is in the lowest energy configuration, which also determines the size of the distance step taken. However as the system approaches the transition state, this gradient gets progressively smaller, as does the step taken in each calculation, which explains why the MEP calculation takes so much longer to reach the transition state compared to the dynamics calculation. The style of the calculation process also means the Minimum Energy Pathway can essentially be defined as the pathway involving the slowest movement of reactants. Since the atoms have no motion at each stage, they also do not have any vibration or kinetic energy, and as a result the mep calculation does not have any relationship to the physical movement of the atoms that occur in order to reach the transition state of the system[1].

In contrast, the Dynamics calculation computes the reaction trajectory as a function of the chemical interaction, temperature, and initial energy, among other factors. The exact parameters taken into account depend on the type of program used. As a result, the trajectory calculated to the transition state does have some physical meaning with respect to the reaction route, and demonstrates key physical parameters such as vibrations. Despite the abstract nature of mep calculations, their use is particularly important in calculating transition states of unknown structural configurations, as well as low-energy reaction routes. Examples of these calculations are demonstrated in the work of P. Janos et al.[2] in determining the reaction pathway of certain enzymes. The mep calculation for the H + H2 system discussed in this report is shown below in Figure 3, while the variation of kinetic energy with time is shown in Figure 4. As discussed, the kinetic energy is constant at 0 throughout the reaction steps, while the pathway directly follows the minimum energy point of the system, showing now system oscillations. This confirms the lack of physical movement parameters involved in the calculation.

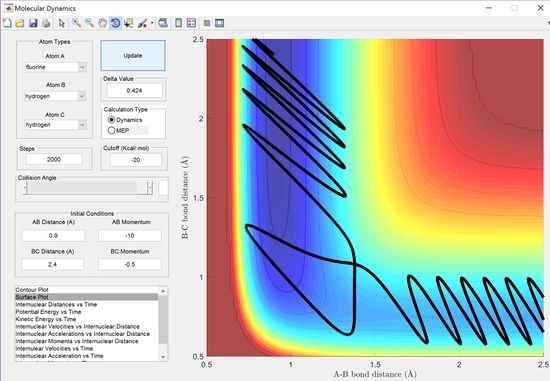

Dynamics Calculations

The surface contour plot of the dynamics calculation is shown below in Figure 5, while the kinetic energy plot of the reaction can be seen in FIgure 6. Following the aforementioned trends, the curved pathway taken to reach the transition state does show oscillation in line with what would be expected from molecular movement. The increase in both value and oscillation of the kinetic energy with time shows the movement away from the transition state, where the vibrational oscillations occur as the reagents in the system regain both momentum and velocity. Both of these graphs evidence the use of physical parameters in describing and predicting the actual movement of the molecules in the system.

The variation of internuclear bond distances and momenta at large time values, achieved by running more steps in the calculation process, shows the product H2-H3 bond length (r1) as remaining constant further from the transition state, while the distance between the molecule and the displaced atom H1 increases with a linear dependency. The graph showing this can be seen below in Figure 7. At 50 seconds, the molecule distance r2 was determined to be 186.5 Å, while r1 was calculated to be 0.756 Å. A snapshot showing the variation of internuclear momentum with time between the species can be seen in Figure 8. As time progresses, the internuclear momentum between B and C increases until it reaches a maximum, the point where there are no more net forces acting on the species to change their internuclear momentum. This value, p2, was calculated to be 2.48 at 50 seconds. The internuclear momentum of H1-H2 can be seen to increase as the atoms form the bond from the transition state and begin to form linear oscillations, with the momentum then also oscillating between two values. The value, p1, was determined to be 1.30 at 50 seconds. These final values can be recorded and taken as the initial values in the reverse calculation (where momenta signs are reversed) to 'trace' back the reaction to the transition state. The parameters can then be changed slightly to determine reactive trajectories for the system, something particularly useful in systems with high activation energies and hard-to-predict trajectories.

Switching the r1 and r2 bond lengths in the dynamics calculations so that r1 = rts and r2 = rts + 0.01 leads to a reversal of the reaction direction. Instead of the calculation moving in the minimum pathway direction of the products, it now travels backwards to form the reactants H3 and H1-H2. The calculation graph showing this trend is shown below in Figure 9.

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) Very good discussion)

Determining Reactive and Unreactive Trajectories

Having determined the minimum energy pathway for the overall reaction, the reagents can be given different parameters in order to determine whether the reaction is successful under a set of predetermined initial conditions. In this case, the momentum of the each of the reagent species can be changed to analyse acceptable trajectories that allow the reaction to occur. The momentum parameters tested in this report, calculated when r1 = 0.74 and r2 = 2.0, are shown below in Table 1, along with a description of the reaction trajectory, an image of the calculation (Figures 10-14), and determination of whether the reaction was successful or not.

| p1 | p2 | Reactivity | Description | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -1.25 | -2.5 | Reactive | H1 forms direct trajectory to attack H2-H3 and form transition state, before H3 leaves and H1-H2 is formed | 10 |

| -1.5 | -2.0 | Unreactive | H1 forms direct trajectory to attack H2-H3 but with insufficient energy, leading to a repulsion that reverses trajectory and reforms the reactants | 11 |

| -1.5 | -2.5 | Reactive | H1 forms direct trajectory to attack H2-H3 and form transition state, which lasts for long time before H3 leaves and H1-H2 is formed | 12 |

| -2.5 | -5.0 | Unreactive | H1 forms direct, high momentum attack trajectory, initially reacting to form H1-H2 via the transition state, before H3 reattacks and reforms H2-H3. H1 reverses trajectory and leaves. Calculation represents barrier recrossing, where H3 has enough resultant energy to reform the transition state and reverse the reaction | 13 |

| -2.5 | -5.2 | Reactive | H1 forms direct, high momentum attack trajectory, reacting to form H1-H2 via the transition state. H3 reattacks and reforms H2-H3, before H1 attacks yet again to reform H1-H2, with H3 then leaving. Residual interactions with the product molecule cause the H3 momentum to oscillate, even though net movement shows the atom as leaving | 14 |

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) Good, but could have had a little more discussion. Not sure what you mean by TS "lasting a long time")

Transition State Theory Assumptions

Transition State theory essentially encompasses the idea that all reactions can be described as passing through a critical transient point of high energy before successfully reacting to form the products, and in doing so attempts to describe the factors affecting the rate of reaction. The activated complex represents the range of configurations surrounding the transition state through which the reactants pass. In order for the Transition State theory to successfully model a reaction, it relies on the following assumptions:

- All reactants are assumed to behave under the conditions set by classical mechanics, in that the collisions and classically derived reactant energies determine the rate of a reaction. A reaction is deemed successful if the reactants have enough energy to collide and pass through the transition state to form the product.

- The reactants must pass through the determined transition state in order to reach the products. Once they achieve the transition state configuration, it is assumed they will automatically form products, and the backward reaction will not occur.

In treating the system as classical, transition state theory neglects important quantum mechanical phenomena, such as tunnelling of light mass species (e.g. protons and electrons). Tunnelling is an instantaneous, distance-dependent process which significantly increases the experimental rate, meaning transition state theory often underestimates the reaction rate in systems involving this transfer.

Secondly, the assumption that reactants will only pass through the saddle point (transition state) of the minimum energy pathway is often not the case, especially under high-energy conditions where various different reactive trajectories can exist that do not pass through the transition state. These trajectories involve a higher activation energy barrier than the saddle point of the reaction, and thus lead to a slower observed rate. The final and perhaps most important limitation occurs when the products formed have enough energy to recross the energy barrier and reform the reactants, slowing the experimental reaction rate.[3][4] An example of this affect is shown above in the trajectory of Figure 13. Once again, this effect slows down the observed rate of reaction, meaning transition state theory overestimates the reaction rate.

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) Very good discussion)

F - H - H system

(Fv611 (talk) 14:02, 9 June 2017 (BST) The whole discussion on this system is excellent. Good job!)

PES Inspection

Reaction Energy Levels & Bond Strengths

The energy level diagram for the reaction F + H2 -> HF + H can be seen below in Figure 15. As can be seen in the trajectory, the reactant energies are much higher, passing through a slightly higher energy transition state before forming the much more stable products of HF & H. This corresponds to an exothermic reaction, and is consistent with the fact that the H-F bond formed in the products is much stronger than H-H in the reactants. The reasoning for this can be explained by the much greater ionic nature of H-F, forming a strongly polarised bond due to the high electronegativity of Fluorine. This is highly stabilised compared to the completely covalent H-H bond. Consequently, the reverse reaction to break the H-F bond and reform H-H is is strongly endothermic, with a high activation energy. This trajectory is shown below in Figure 16.

Locating the Transition State & Calculating Activation Energy

The transition state for this reaction was located by using Hammond's postulate, which essentially determines that the transition state will be most similar in its characteristics to the state which it is closest to, in this case the reactants. This means that the nature of the transition state, including atomic distances, will be close to those of the reactants, and from this the transition state was able to be localised. The starting bond length for H2 and HF were taken and then slowly increased until the transition state was achieved. The approximate transition state values were calculated to be r1 = 0.742 Å (3 d.p.) and r2 = 1.812 Å (3 d.p.), with the intermolecular distance variation with time shown in Figure 17. The variation of kinetic energy with time is shown below in Figure 18.

As can be seen in both figures, there is some very small residual oscillation in both the momentum and kinetic energy of the approximated transition state coordinate, consistent with previous discussions surrounding the inability to isolate the transition state in the reaction calculations.

The activation energy for both the forward and backward reactions was calculated using an mep calculation starting at a slight displacement from the approximated transition state of the reaction, before being compared to the energy minima on the reactant and product trajectories. For both reactions, the energy of each state is given in the table below, while the activation energies were calculated to be:

- F + H2 -> HF + H: Ea = 0.27 kcal/mol

- HF + H -> F + H2: Ea = 30.27 kcal/mol

| State | Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Transition State | -103.75 |

| F + H2 | -104.02 |

| HF + H | -134.02 |

Reaction Dynamics

Successful Initial Reaction Trajectory

A successful reaction trajectory was established for F + H2 -> HF + H, with the parameters used and surface energy plot shown below in Figure 19. The variation of internuclear distances with time can be seen in Figure 20. As can be seen from the graphs, the products form high momentum and kinetic energy trajectories, a result of the fact that energy is conserved in the system. As the reactants come together, the kinetic energy they have is converted to potential energy, where the maximum corresponds to the transition state. The product formation then converts this gained potential energy into vibrational energy, thus explaining the significant oscillations in the product molecules. The kinetic energy obtained by the products is indeed significant enough to reform the reactants for a short while, before the system then resumes a trajectory towards the product molecules. In order to experimentally confirm this observation, vibrational spectroscopy could be used to compare the oscillation frequencies of the products compared to the reactants. It would be expected that H-F would have a higher frequency absorption compared to H2 based on the conversion of potential energy into vibrational energy. However, this would be experimentally difficult as complete isolation of the system is hard to achieve.

Alternatively, in order to confirm whether the products are in a vibrationally excited state, calorimetry could be used to determine the heat emission to the external environment as the products undergo vibrational relaxation. The amount of heat released would correspond to the vibrational excited state of the molecule when it is first formed. This would be easier to isolate as a system compared to IR spectroscopy.

Polanyi's Empirical Rules & Transition State Positioning

Polanyi's empirical rules essentially link Hammond's postulate (regarding the relative position of the transition state with respect to reactant and product molecules) to the relative energy distribution of energy within the system. More specifically, Polanyi found that a reaction with an early transition state favours pathways where the reactants have low vibrational energies and high translational energies. This is due to the fact that molecules with high vibrational energies due not have enough translational energy in the direction of the reaction coordinate to reach and overcome the transition state. Reactants with high translational energy high directional energy and are able to surmount the activation barrier, forming products with high vibrational energies.

Conversely, for a system with a late transition state, the opposite effect is true, where molecules with high translational energies essentially hit and bounce back off the inner wall of the potential surface diagram. In this case, reactants with high vibrational energy that form an in-phase collision trajectory easily surmount the transition state to form the products, often with products of high translational energy[5][6]. In order to demonstrate this effect, the initial momenta and vibrational energy for the reactants in the reactions H2 + F -> HF + H and H + HF -> F + H2 were varied in order to demonstrate the application of Polanyi's rules.

For the exothermic reaction H2 + F -> HF + H, which features an early transition state, the H2 molecule was first given a low vibrational energy, while F was given a comparatively large momentum value. The reaction trajectory for this calculation was successful and is shown below in Figure 21. In contrast, when the system was given a high H2 vibrational energy and a low F translational energy, the system was unable to reach the transition state and cause a reaction, leading to an unsuccessful trajectory. This can be seen in Figure 22.

For the reaction HF + H -> H2 + F, the reverse effect was seen, where a low translational energy and high vibrational energy led to a successful reaction, shown below in Figure 23. Conversely, a high translational energy and low vibrational energy produced the 'bounce back' effect discussed earlier, with the unsuccessful trajectory shown below in Figure 24.

References

- ↑ W. Quapp and D. Heidrich, Theor. Chim. Acta, 1984, 66, 245–260.

- ↑ P. Janos, T. Trnka, S. Kozmon, I. Tvarovska and J. Koca, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2016, 12, 6062–6076.

- ↑ P. Atkins and J. De Paula, Atkins’ Physical Chemistry, 10th Edition, 2009.

- ↑ Levine I, Physical Chemistry, 6th Edition, 2009

- ↑ J. C. POLANYI, Science (80-. )., 1987, 236, 680–690.

- ↑ H. Guo and K. Liu, Chem. Sci., 2016, 7, 3992–4003.