MRD:01339518

Exercise 1

"On a potential energy surface diagram, how is the transition state mathematically defined? How can the transition state be identified, and how can it be distinguished from a local minimum of the potential energy surface? "

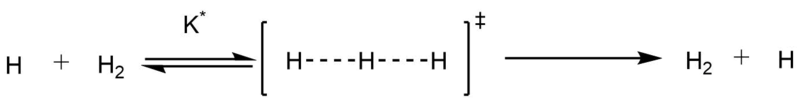

By definition[1], the transition state on a potential energy surface must follow the following condition:

Where initially, is the distance between the colliding hydrogen atom and the diatomic, and is initially the bond length of the diatomic hydrogen.

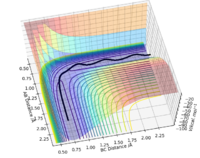

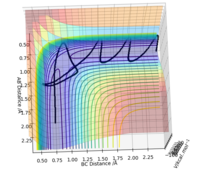

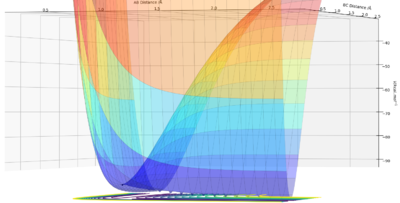

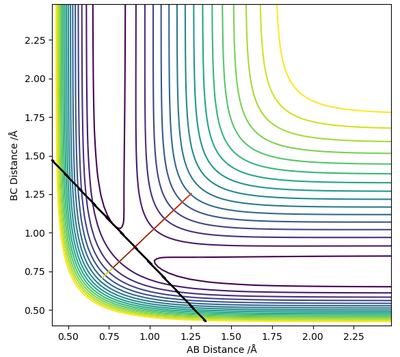

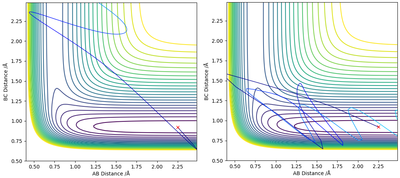

Visually, it is the lowest energy point on the ridge that rests between the reactant and product channel (Fig 1). If you consider taking the second derivative of the reaction path (X) and the vector perpendicular to the reaction path (Y), this results in the second conditions the transition state obey. The transition state is, therefore, a minima and a maxima on the potential energy surface. and

Good, but you should mention that ordinary local minima don't have the variation in second derivatives. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

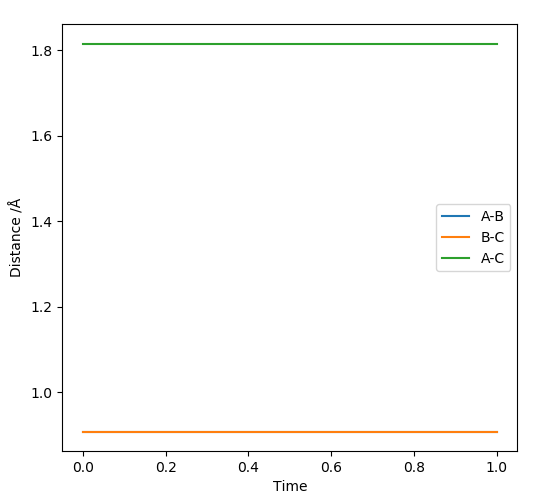

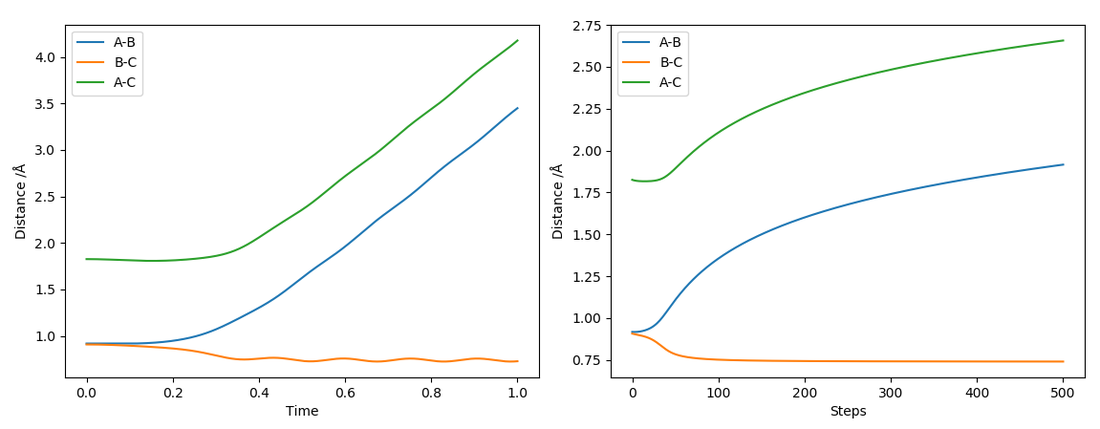

"Report your best estimate of the transition state position rts and explain you reasoning, illustrating it with a 'Internuclear Distances vs Time" plot for a relevant trajectory"

By definition, the transition state is the maximum on the minimum energy path (mep). Therefore, along the ridge represented by X, the transition state is the lowest point along that ridge, and the maximum, along the vector Y, the reaction path.

To find the position of the transition state, the forces that occur along the ridge must be as close to 0 as possible to find the minimum energy. As a result of the vectors being 0, this means that no oscillation occurs along the ridge, which results in the internuclear distances remaining constant (Fig 3). The reasoning for this is because force is defined as . The definition of the transition state requires the forces to equal 0.

The outputs from the estimate of rts are shown below.

| Conditions | |

| rts | 0.907742 Å |

| Force along AB | +0.000 |

| Force along BC | +0.000 |

| Potential energy | -99.305 kJmol -1 |

| Kinetic Energy | 0.000 kJmol -1 |

| Total energy | -99.305 kJmol -1 |

"Comment on how the mep and the trajectory you calculate differ."

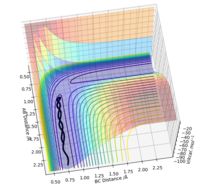

The mep is the minimum energy path along the potential energy surface. The mep considers that the molecule take infinitesimally small changes in distance. Therefore,

This results in kinetic energy equalling zero and any remaining energy is a result of the position of the internuclear separation distances. The mep follows the path at the bottom of the energy wells in both the reaction and product channel. In quantum mechanics, the simple harmonic oscillator model shows that for a ground state particle, the particle has a zero point energy which allows the particle to still vibrate, which means that the molecule undergoes an exchange of potential and kinetic energy. However, the mep requires the molecule to take the lowest potential energy along the potential energy surface. The molecule therefore resides at the very bottom of the potential energy well, analogous to that seen in classical mechanics.

As a result of the lack of vibrations, the mep pathway is smooth and no oscillation can be seen. Whereas in comparison with the dynamic trajectory, the oscillation of the molecule can be seen.

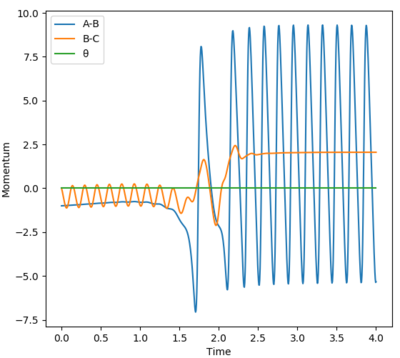

"Complete the table above by adding the total energy, whether the trajectory is reactive or unreactive, and provide a plot of the trajectory and a small description for what happens along the trajectory. What can you conclude from the table?"

The kinetic energy where p1 = -2.5 and p2 = -5.0 had a total energy 20 kJmol-1 higher than the conditions where p1 = -1.5 and p2 = -2.5. Sufficient energy in the system that is above the activation energy is not the only factor for whether a reaction is reactive.

The H2 molecule was vibrating, and at the approach of the transition state, where it was near the value rts, the molecule BC had relaxed. It was no longer in the correct phase for the reaction to occur. While there was sufficient kinetic energy, it was in the incorrect phase for reaction. It did result in an excited vibrational state though.

In contrast, for the condition where p1 = -2.5 and p2 = -5.2, the kinetic energy was high enough to surpass the activation energy, and this resulted in an excited vibrational state for the product H2

Good. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

State main assumptions of transition state theory. Given the results, how do TS theory predictions compare to experimental values for reaction rates?

The first assumption made is that all reactants populate the energies as they would with a Boltzmann distribution [2].

The second assumption is that all reactions undergo a quasi-equilibrium. The reactants are in equilibrium with the intermediate, A.K.A, the transition state.

The third assumption is that as soon as the trajectory has passed the transition state, the product will not revert back to the reactants. This is at odds with the experimental results in the table above.

All assumptions here are shown in the equation below.

The equilibrium constant is defined as,

From this, the concentration of the transition state can be found.

The rate of product formation can then be found,

can be simplified to

Given the second assumption

You mean third? Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

, transition state theory predictions tend to be faster than the experimental values, as does not consider the small but significant possibility of recrossing, as it is calculated through classical mechanics. The phenomenon of recrossing occurs primarily due to the need for the molecules to approach the molecules in the correct orientation, be it by collision angle, or the vibrational state of the molecule.

Transition state theories fourth assumption is that for a reaction to occur, the molecule must have enough energy to bypass the activation energy barrier. However, this discounts the possibility of the reaction bypassing the barrier by quantum tunnelling. While tunnelling has a very small probability, it is most significant for light atom systems [3].

Exercise 2

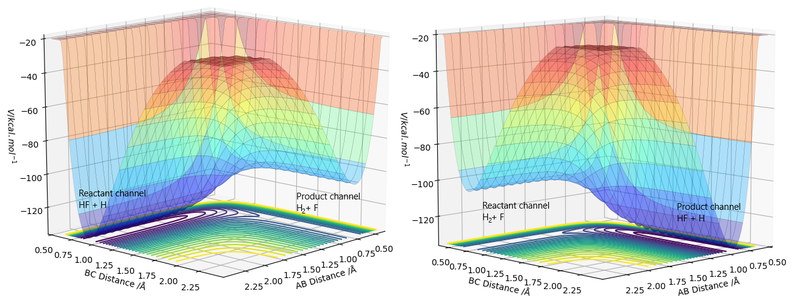

"By inspecting the potential energy surfaces, classify the F + H2 and H + HF reactions according to their energetics (endothermic or exothermic). How does this relate to the bond strength of the chemical species involved?"

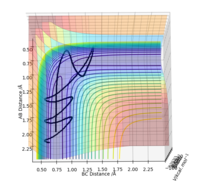

The H-F bond (565 kJmol-1) is a much stronger bond than the H-H bond (464 kJmol-1), with a difference of 129 kJmol-1 in their bond dissociation enthalpies [4]. Therefore, for F + H2, it is exothermic. For H + HF, it is endothermic. This is seen in the difference in the height on the potential energy surface diagrams.

Correct Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

Position of transition state and activation energy

| Reaction | Activation Energy /kJmol-1 | ratom /Å | rdiatomic /Å |

|---|---|---|---|

| F + H2 | 0.268 | 1.8108755 | 0.7448758 |

| H + HF | 30.273 | 0.7448758 | 1.8108755 |

From Hammond's postulate, the geometry of the transition state is most similar to the side of the reaction with the most similar energy. Therefore, for H + HF, the transition state is late, as the reaction is endothermic, and energy is required to separate the hydrogen from the fluorine. Whereas with F + H2, the transition state is early.

As before, to find the transition state, the conditions were found through experimentation to find the values which corresponded to the force vectors equalling 0. The energy of the transition state was found to be -103.752 kJmol-1. The activation energy was found by considering the energies of the reactants in isolation by increasing the separation between the species.

The program gives energies in kcal per mol not kJ, it doesn't look like you did a conversion as your kJmol-1 values are correct for kcal-1. Graphs would have made this clearer, but the question says to just report activation energies so they are not necessary. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

"In light of the fact that energy is conserved, discuss the mechanism of release of the reaction energy. Explain how this could be confirmed experimentally"

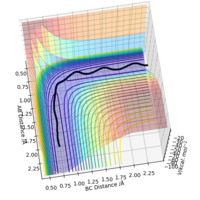

For the reaction F + H2, with the input parameters shown in the table, the resultant trajectory is reactive. Note that both the product(HF or AB on Figure 6) and the reactant(H2 or BC on Figure 6) are vibrationally active. Use of an IR spectrometer to measure the emission spectrum from the system would confirm the vibrational states of the molecules when they undergo vibrational relaxation.

| Conditions | Momentum | Separation / Å |

|---|---|---|

| F | -1 | 0.76 |

| H2 | 0 | 2.25 |

You should mention heat being released, this would also lead on to using a calorimeter to confirm the release of reaction energy. Using a calorimeter would be much easier than monitoring the reaction by IR. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

Discuss how the distribution of energy between different modes (vibration and translation) affect the efficiency of the reaction and how this is influenced by the position of the transition state

For the reaction H + HF (rHH = 2.25 Å, rHF = 0.92 Å), as it is endothermic, the transition state is late. The position of the transition state influences the most efficient type of energy for the reactants. For example, For the case where H is given an extremely large amount of kinetic energy (pH = -15,pHF=-1 ), the trajectory is still unreactive (Figure 7). However, when HF is vibrationally excited (pH = -1,pHF=-15 ), the trajectory can be reactive (Figure 7).

In the case where the H atom has high kinetic energy, the atom approaches the HF molecule and gets close enough to the point where the repulsive forces become too high for it to bypass. However, when the HF molecule is vibrationally excited can bypass the molecules more easily without experiencing the same repulsive forces [5].

Would help to mention Polanyi's rules. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

Overall this is a good report, well done. Pu12 (talk) 22:41, 16 May 2019 (BST)

References

<references> [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Steinfield JI, Francisco JS, Hase WL. Chemical kinetics and dynamics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1989. p 309

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Steinfield JI, Francisco JS, Hase WL. Chemical kinetics and dynamics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1989. p 311

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Steinfield JI, Francisco JS, Hase WL. Chemical kinetics and dynamics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1989. p 336

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Atkins P, D Paula J. Physical Chemistry. 10th Editi. Oxford University Press; 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Steinfield JI, Francisco JS, Hase WL. Chemical kinetics and dynamics. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1989. p 297-299