MRD:01047192

Vince's Page

(Fv611 (talk) 15:27, 17 May 2017 (BST) Overall a very nice report. Well done!)

Section one

Question 1

Q: What value does the total gradient of the potential energy surface have at a minimum and at a transition structure? Briefly explain how minima and transition structures can be distinguished using the curvature of the potential energy surface.

A: At a minimum and a transition state the gradient of the PE surface is zero. The two can be distinguished by looking at points very close to the minimum/transition state. If the point is a transition state, the second partial differential of one direction (could be r1 or r2) will be positive and the other will be negative. If the point is a minimum both second differentials will be positive.

Question 2

Q: Report your best estimate of the transition state position (rts) and explain your reasoning illustrating it with a “Internuclear Distances vs Time” screenshot for a relevant trajectory.

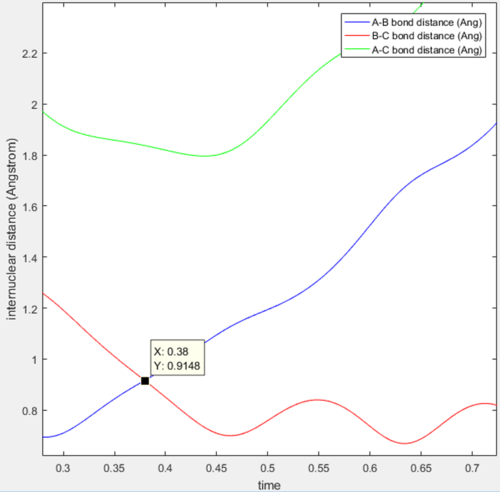

A: Best estimate r1=r2=0.9148

This image shows the point where the transition state occurs in the simulation when the reaction occurs. At this point where the lines cross r1=r2=TS position so finding the value gives the best estimate of the transition state position. Here the Y value shown is the result we're looking for.

(Fv611 (talk) 15:27, 17 May 2017 (BST) Good, could have mentioned the lack of oscillation at the TS like you do in the fluorine system)

Question 3

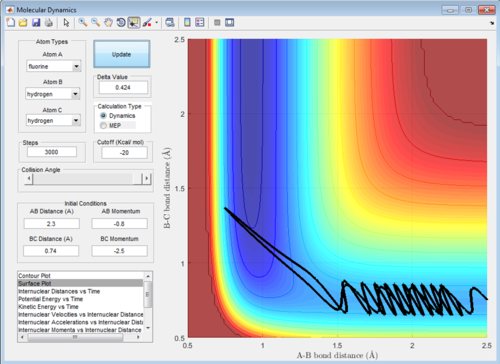

Q: Comment on how the mep and the trajectory you just calculated differ.

A: In the mep there is no oscillation in the trajectory unlike in the dynamics calculation (both shown below, dynamics left). This is because the mep calculation only finds the absolute minimum of the potential energy surface, in the dynamic calculation the molecule and atom are oscillating so do not precisely follow the minimum.

(Fv611 (talk) 15:27, 17 May 2017 (BST) Yes, but why?)

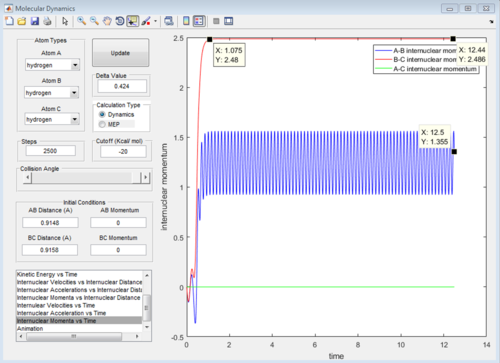

At large t the final r values are as expected. From t=0 the 2 joined hydrogens move away together, so r1 will stay almost constant (but still oscillating), the third atom moves away from the molecule so the r2 distance will be very large in comparison. As the molecule repels the single atom, the momenta of both increases as they pick up speed. Once they are far enough that they are no longer repelling significantly (at around t=1.08) they continue at the speed reached. For the atom with no oscillation this is constant so the graph levels off. For the molecule still oscillating the overall momentum oscillates as the atoms continuously exchange kinetic energy for potential energy. The discussed graphs are shown below.

In this question we have used r2=rTS and r1=rTS+0.01, and the result is the trajectory trailing off as BC distance increases. Should we have used r1=rTS and r2=rTS+0.01, the only difference would be the trajectory would be seen trailing off to the right, with AB distance increasing. Since we would have shifted the starting positions away from TS in the other direction. This can be visualised by thinking of a ball being placed on either side of a hill; the ball will roll in the direction it initially faces and not back up over the hill to the other side.

Question 4

Q: Complete the table by adding a column reporting if the trajectory is reactive or unreactive. For each set of initial conditions, provide a screenshot of the trajectory and a small description for what happens along the trajectory.

A:

| p1 | p2 | Reactive? |

|---|---|---|

| -1.25 | -2.5 | Yes |

| -1.5 | -2.0 | No |

| -1.5 | -2.5 | Yes |

| -2.5 | -5.0 | No |

| -2.5 | -5.2 | Yes |

1st trajectory: Initially there is no oscillation, this is because both atoms B and A have zero momenta relative to eachother (and being the same mass identical velocity), so despite being bonded they don't oscillate. The reaction occurs and molecule BC is formed, which oscillates now as after exchange the 2 atoms in the molecule don't have the same momentum.

2nd trajectory: The molecule AB and atom C meet but don't have enough energy to overcome the transition state, so simply repel eachother. No reaction occurs.

3rd: Molecule AB oscillating due to non-zero relative momentum meets atom C with enough energy to overcome transition state energy barrier, molecule BC is formed and A and BC repel eachother after the reaction so AB distance increases.

4th: Initially molecule AB is not vibrating because both atoms B and A have zero momenta relative to eachother, as seen in 1st case. The total momentum in the system is large here, the energy barrier is easily overcome, BC is formed, however C having a large relative momentum to B and A a low relative momentum to B after the collision resulted in AB reforming stably but with violent oscillation. C is repelled.

5th: A case similar to 4th, however here after BC forms and AB reforms, BC then forms yet again and remains. Also similar to 1st and 4th and for the same reason AB is not oscillating initially.

Question 5

Q: State what are the main assumptions of Transition State Theory. Given the results you have obtained, how will Transition State Theory predictions for reaction rate values compare with experimental values?

A: TST = transition state theory

1) TST assumes that that atomic nuclei behave according to classical mechanics, and ignores the possibility of tunneling giving rise to a reaction occurring despite the reactants not having sufficient energy to overcome the barrier. The effect would be that using TST we would underestimate the rate of a reaction, as any reactions occurring via tunneling would not be counted.

2) TST assumes the system will always pass through the lowest energy saddle point, however at high temperatures this assumption is invalid, as molecules have enough energy to reach saddle points higher than the minimum. The assumption doesn't hold up for the modelled H-H H interaction, in none of the cases so far has the reaction trajectory matched the mep, the reaction will (almost) always not go over the very lowest energy saddle.

3) It assumes each intermediate is long-lived enough to reach a boltzmann distribution of energy states, so when intermediates are short lived TST fails, the momentum of reactants forming one intermediate can have an effect on sequential intermediates. We see this assumption in the 4th and 5th above trajectories, where the previous momentum of reactants causes the reactants to form products and then reform afterwards. According to TST this should not happen.

4) There is a dynamic bottleneck for the reaction, and if there are several two bottlenecks can't interact. Also, once the system passes the energy barrier it is assumed the reaction cannot reverse. Trajectories 4 and 5 dispute this, after products are formed they recross the barrier against the assumption. The effect on reaction time for example would be an overestimate using TST, as all unproductive backwards reactions that reform reactants are ignored.

5) The potential energy surface is strictly separable at the transition state, i.e. there is no dynamic coupling between the reaction coordinate motion and any other modes of motion when the reaction is in the close to the transition state.

6) Assumes there is only 3 states available; the reactants, the transition state, and the products. This assumption would fail in any reaction which has an intermediate state.

References: 1) Eyring, H. (1935). "The Activated Complex in Chemical Reactions". J. Chem. Phys. 3 (2): 107–115. doi:10.1063/1.1749604 2) Masel, R. (1996). Principles of Adsorption and Reactions on Solid Surfaces. New York: Wiley 3) Pineda, J. R.; Schwartz, S. D. (2006). "Protein dynamics and catalysis: The problems of transition state theory and the subtlety of dynamic control". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 361 (1472): 1433–1438. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1877. PMC 1647311Freely accessible. PMID 16873129

Section 2

Question 6

Q: Classify the F + H2 and H + HF reactions according to their energetics (endothermic or exothermic). How does this relate to the bond strength of the chemical species involved?

A:

F + H2: exothermic, the energy of products (H2 + F) is lower than reactants (HF + H) as seen in the model. This means that the H-F bond energy is greater than the H-H bond energy, therefore when we break a H-H bond to form a H-F bond there is some heat produced.

HF + H: Endothermic, (as the reverse reaction it must be), the energy of HF + H is lower than F + H2. When a H-F bond is broken to form a H-H bond the system cools correspondingly, therefore H-F bond is stronger. This is illustrated below, we can see that the end point is higher than the initial point.

Question 7

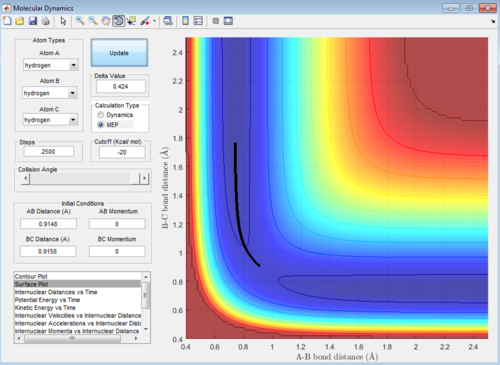

Q: Locate the approximate position of the transition state.

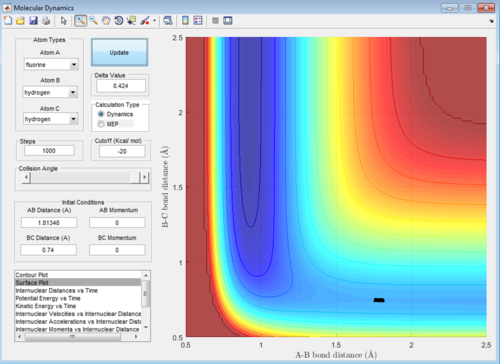

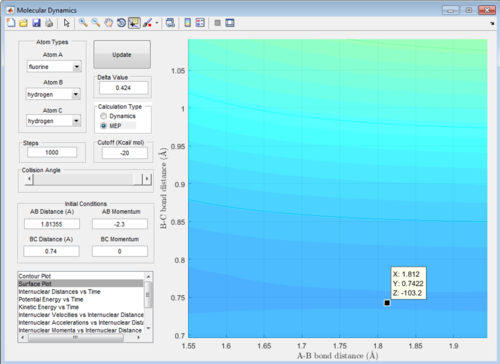

A: At the transition state the gradient of the surface plot is zero, if we were to place a ball with 0 energy directly on the transition state it should never move, therefore if one was to place reactants directly on the transition state with zero energy they would never react, but remain in the transition state forever. Using the mep function, if we start the calculation directly on the the transition state, the computer should be unable to find any minimum energy path, as moving from the state requires an increase in energy. Therefore when we set mep to start with the exact right internuclear distances, it should display no pathway regardless of how many steps are calculated. The same should apply to the dynamics function with 0 initial momenta, the system should not move from the transition state if placed directly on it. Below are screenshots of the calculated transition state location: AB = 1.81355, BC = 0.74

Slightly smaller AB

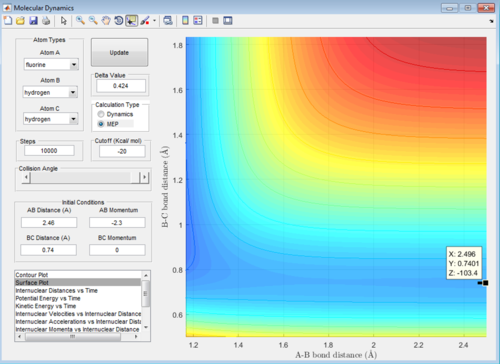

Exact transition state

Slightly greater AB

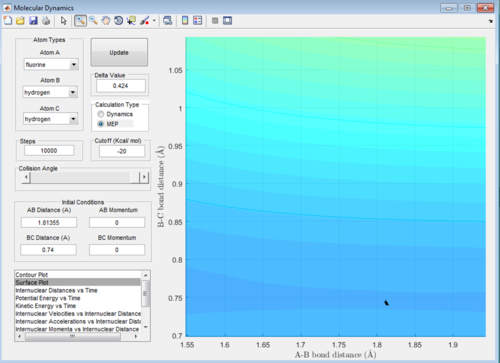

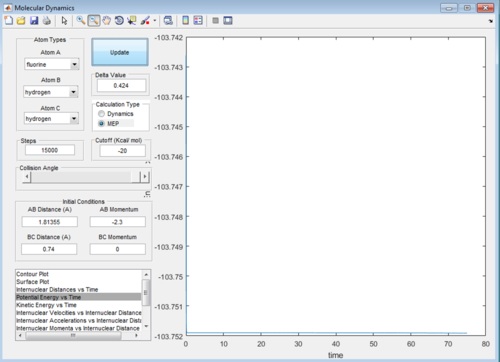

mep function after 10000 steps at transition state

Potential energy vs time with mep at 15000 steps starting at the transition state position, as seen the flat line at the bottom of the graph demonstrates that even over large time spans the system has remained exactly at the same point in potential energy.

Here with a slight alteration in initial position from TS the potential energy changes with time, the system would be exchanging potential energy for kinetic as time passes (the ball is rolling down the hill in our analogy).

Question 8

Q: Report the activation energy for both reactions.

The activation energy is the energy required to go from stable reactants (whether you choose "reactants" to be HH and F or HF and H) to the transition state. The surface plot can be used to find this value, we use the mep function to plot a point at the minimum energy at large AB (so separated HH and F by a large distance in this case) to give the z value which equals the potential energy of the separated atom/molecule. Next plotting a point exactly on the transition state to give the potential energy of the transition state. The difference of these two potential energy values is the activation energy, which could be thought of as how much energy would be required to push a ball up to the top of a hill from the bottom.

As seen below the calculated value for the activation energy of HH + F is -103.2-(-103.4)=0.2kcal/mol, this is E(TS)-E(reactants).

The plotted point along mep giving energy of separated HH and F

The plotted point at the transition state

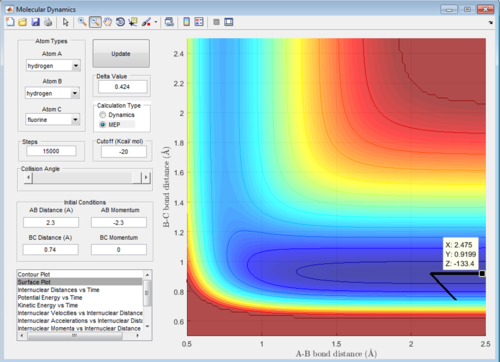

As seen below the calculated value for the activation energy of HF + H is -103.2-(-133.4)=30.2kcal/mol. This is using the TS energy already found above.

The plotted point along mep giving energy of separated HF and H

Question 9

Q: In light of the fact that energy is conserved, discuss the mechanism of release of the reaction energy. How could this be confirmed experimentally?

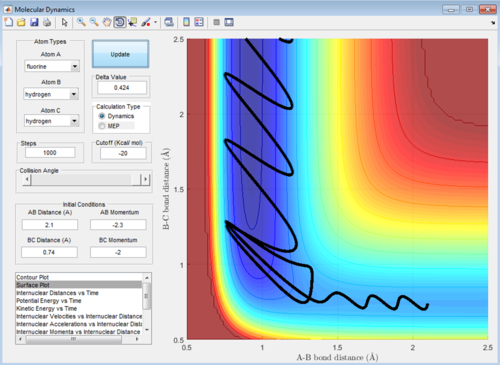

The reactive trajectory shown below:

It can already be seen that when the reaction path leads to products, there is a far larger oscillation up and down the potential well.

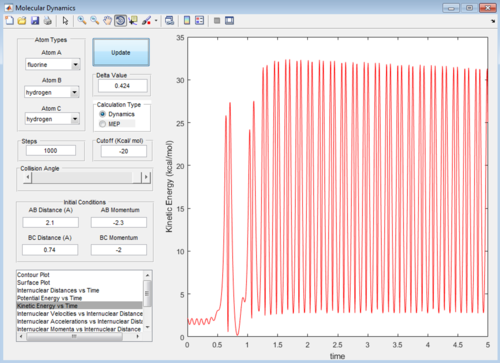

Below can be seen a kinetic energy plot, as time goes on and the reaction progresses kinetic energy is generated from the reaction.

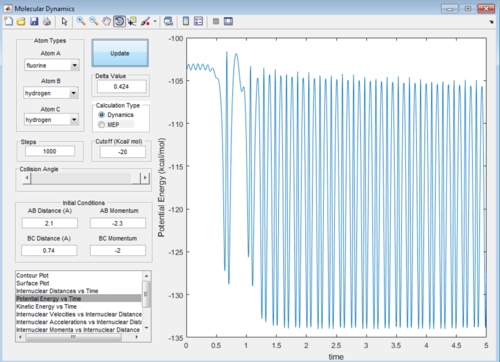

Below is a potential energy plot, as time goes on potential energy is lost, in equal and opposite proportion to how kinetic energy is gained, therefore the mechanism for release is to transfer potential to kinetic.

This kinetic energy increase in molecules is an increase in heat energy on the large scale (as random molecular kinetic motion is heat), therefore a calorimeter could be used to measure the heat energy change during the reaction, we would observe a large increase in temperature as the reaction progressed, confirming the prediction.

Question 10

point 1: Varying HH momentum between high negative and positive values always give larger amounts of oscillation in the products section, reaction trajectories are not reactive for high values of HH momenta, so are inefficient for the reaction.

point 2: When setting the HF momentum slightly higher and making the HH oscillation very small, a successful reaction is observed. Therefore it seems a large amount of HH vibration inhibits the reaction despite adding a large amount of energy, while adding a small amount of momentum to the F atom allows the reaction to take place at a lower overall energy.

Q: Discuss how the distribution of energy between different modes (translation and vibration) affect the efficiency of the reaction, and how this is influenced by the position of the transition state.

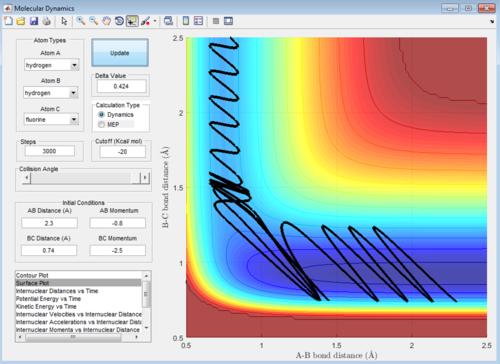

Polanyi's rules state that vibrational energy is more efficient at promoting a late barrier reaction than translation energy is. [1] For the reaction HH+F the barrier is early, and so a low vibrational energy in HH leads to reaction, and can be described as efficient - we want the F to have high energy and the HH vibration to be of low energy to have a successful reaction as shown below.

The opposite will be true for the reverse reaction, as here the barrier is late, we want a high vibrational energy as polanyi's rules predict, a screenshot below illustrates this, when we start with HF and a large vibration the reaction occurs, so this if efficient. Note a late barrier means the transition state occurs near the end of the reaction, and an early barrier means the TS occurs near the start. For completeness there is a screenshot of HH+F high vibration failing.

HH + F low vibration

HF + H high vibration

HH+F failing

reference: [1] = [Z.Zhang et al., "Theoretical Study of the Validity of the Polanyi Rules for the Late-Barrier Cl + CHD3 Reaction" J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 2012, 3 (23), pp 3416–3419 DOI: 10.1021/jz301649w]