Jc1506:copley01

Dimerisation of cyclopentadiene

Cyclopentadiene dimerises readily by a π4s + π2s mechanism to yield exclusively the endo- product. MM2 mechanics have been used to show that this is of the order of 2 kcal/mol more stable than the exo- configuration, which is not formed. As both of these forms are symmetry allowed[1] it is clear that the reaction is not under thermodynamic control. The most common explanation for this selectivity was postulated by Woodward and Hoffman[2], and describes the "second order orbital overlap" effects, that is, overlap of the in-phase portions of the HOMO of the diene with LUMO of the dienophile and vice versa, stabilising the transition state to such an extend that it determines the sole product of the reaction.

However, this phenomenon is also observed in the reactions of cyclopropene as dienophile, albeit to a lesser extent. This led Hendon and Hall [3] to put forward an explanation based on extended Huckel calculations that stated that the Woodward-Hoffmann effect is actually minor, and that the origin of the selectivity is the greater orbital overlap caused in forming the endo- product.

It is observed experimentally[4] that hydrogenation of the double bond in the norbornene moiety of dicyclopentadiene is far quicker than hydrogenation of the double bond in the 5-membered ring. Hence product 4 is formed preferentially over product 3, this would be predicted from thermodynamics since 4 is ~5 kcal/mol more stable than 3. On inspection of the results from MM2 optimisation, it can be observed that the origin of this difference in stablity largely comes from the "Bend", that is that in 3 the bond angles are held further from their natural geometry than in 4. This is particularly evident around the remaining double bond in 3 where the ring shape restricts the C-C-C bond angle at the sp2 carbon to 108o, compared to a C-C-C bond angle of 112o for molecule 4 as the geometric demands of a cyclopentene moiety are less than those of a norbornene.

| Exo- (1) | Endo- (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2883 | 1.2485 | 1.2308 | 1.0910 |

| Bend | 20.5855 | 20.8604 | 18.9806 | 14.5588 |

| Stretch-Bend | -0.8388 | -0.8370 | -0.7610 | -0.5505 |

| Torsion | 7.6566 | 9.5112 | 12.0904 | 12.4832 |

| Non 1,4-VDW | -1.4192 | -1.5608 | -1.4920 | -1.0843 |

| 1,4-VDW | 4.2276 | 4.3316 | 5.7307 | 4.5256 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.3777 | 0.4493 | 0.1631 | 0.1405 |

| Total | 31.8777 | 34.0032 | 35.9425 | 31.1643 |

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic additions to a pyridinium ring (NAD+ analogue).

The reaction of Grignard reagents is most rapid where the magnesium can complex to a species with lone pairs. This can lead to the transition state possessing the character of a six-membered ring. This is illustrated below. The notable thing for this molecule is that no energy minimum exists with the carbonyl pointing down as drawn, in the lowest energy conformations found by MM2 the carbonyl points up with a dihedral angle of 20-35 degrees. By holding the dihedral angle at -30o (i.e. 30 degrees into the plane of the screen) an energy of 31kcal/mol was recorded, 5kcal/mol higher than the lowest energy for the carbonyl pointing up. Image:carbonyldown.jpg|thumb|Molecule 5 with carbonyl pointing down, a very high energy conformation]] It is reasonable to suggest that the methyl group of the Grignard reagent is delivered in a conjugate fashion, via a six-membered ring transition state. With the carbonyl only able to occupy one face of the ring, addition must then occur from this face. Although the transition state is impossible to optimise with MM2 (due to its inability to cope with the Mg atom), the transition state is expected to take on thr rough form illustrated.

An interesting constraint on the structure is that the amide nitrogen is ideally planar maximising orbital overlap with the carbonyl and hence maximising conjugation with the pyridine ring and adjacent oxygen atom. However the steric constraints of this seven membered ring force it to adjust somewhat. The energy of the conformation is found to decrease as the dihedral angle of the carbonyl is increased, with several local minima apparent. After extensive manual movement of atoms, the conformation thought to be the global minimum had an energy of 26.3kcal/mol, and a carbonyl dihedral of 23 degrees.

NAD+ analogues can be used as "chiral amide transferring agents"[5]. For this to occur, the aniline must bond with regio and stereoselectivity to the NAD+ analogue, before reacting with the electrophile. In molecule 6, the methyl on the 7-membered ring, drawn coming out of the plane, directs the carbonyl into the plane. This molecule can also exist as the alternative atropisomer, with carbonyl coming out and methyl going into the plane of the screen. In the atropisomer of molecule 6, the carbonyl group sterically inhibits attack of the amine on the bottom face of the pyridinyl ring, hence attack comes from the top face giving the stereochemistry shown in product 8.

| Up atropisomer | |

|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.6359 |

| Bend | 7.6887 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3452 |

| Torsion | -6.5065 |

| Non 1,4-VDW | -1.3772 |

| 1,4-VDW | 17.5494 |

| Charge/Dipole | 2.5118 |

| Dipole/Dipole | -4.7991 |

| Total | 17.0481 |

| Carbonyl dihedral angle | -45 deg |

Taxol

An intermediate in the total synthesis of taxol has been shown to show atropisomerism. The two antropisomers were drawn in ChemBio3D and optimised using MM2. Then extensive manual moving of atoms was required to try and find the global minimum. Techniques used included trying to convert the six membered ring to a chair form, whilst maintaining the syn- nature of the two protons at the ring junction. Maintaining the stereochemistry of the double bond, it was desirable to make chair shapes in the 10-membered ring.

| Up atropisomer | Down atropisomer | |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 2.6836 | 2.5620 |

| Bend | 15.8220 | 10.7581 |

| Stretch-Bend | 0.3949 | 0.3189 |

| Torsion | 18.2716 | 19.8168 |

| Non 1,4-VDW | -1.1085 | -1.4730 |

| 1,4-VDW | 12.6795 | 12.5463 |

| Dipole/Dipole | 0.1470 | -0.1814 |

| Total | 48.8902 | 44.3478 |

The two atropisomers were distingushable largely by the orientation of the carbonyl group. Upon standing, the 'up' atropisomer isomerises to the 'down' atropisomer. The origin of the up isomers relative instability is principally the constraint at the sp2 carbonyl carbon to have bond angles of 115, 126 and 119 degrees, whereas the 'down' isomer has three equal angles of the usual 120 degrees. This manifests itself in the large difference in the "Bend" component of the energy output (see below).

It is interesting to note that these alkenes are next to a bridgehead. This goes against Bredt's rule[6], which states alkenes are generally found next to a bridgehead due to the pyramidisation of the alkene resulting in poorer π-overlap between carbon p-orbitals. However, MM2 optimisation of the hydrogenated equivalent of this alkene yielded a structure with massive energy contributions from torsional strain and 1,4-van der Waals repulsions. There is however another effect which could cause this "hyperstability"[7]. It is possible to draw a tautomerised form of the molecule whereby the carbonyl enolises in a transannular fashion. This is analagous to the "homoaromaticity" of the norbornyl cation and illustrates the low electron density of the alkene bond, suggesting which it has such great stability.

Peptide Hydrolysis

For cis-decalin derivative 13 the conformation with the amide substituent equitorial is ~6 kcal/mol more stable, hence the vast majority of molecules of 13 will lie in this conformation. In these systems of relative conformational flexibility, it is the likelihood of the two functional groups being in close proximity that determines the reaction rate, rather than the relief of steric strain as in other cases.[8]. The equitorial conformation fulfils this proximity hence reaction is rapid in this case. Likewise, for the trans decalin derivative 14, the equitorial conformation is the most stable. However, in this case the reacting groups are far apart in space, so 14 must flip to give the axial conformation before reaction can take place. This is an example of the Curtin-Hammett principle whereby the major conformation of a reaction mixture may not be the most reactive. The enthalpic cost of this switch has been calculated to be ~5 kcal/mole hence reaction is much slower.

| cis-decalin equitorial | trans-decalin equitorial | cis-decalin axial | trans-decalin axial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 17.1577 | 11.2211 | 23.2625 | 16.8031 |

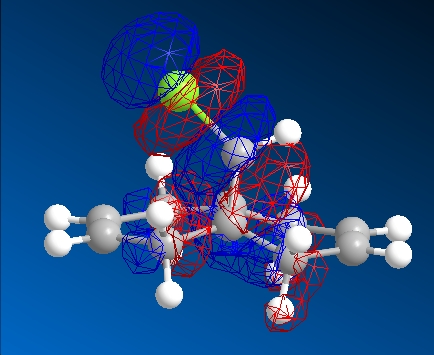

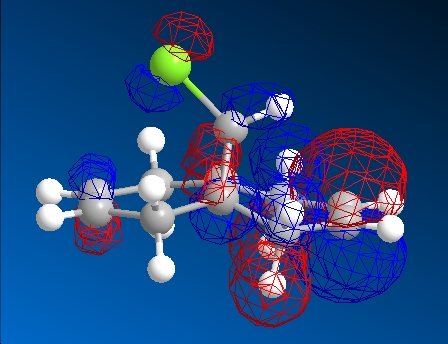

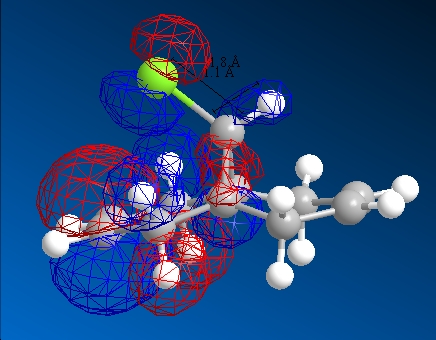

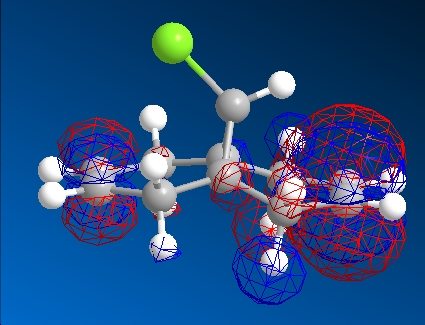

Regioselective addition of Dichlorocarbene

Firstly, the chlorodiene was drawn in ChemBio3D and optimised by the MM2 force field to give the following moecule (Energy: 17.91kcal/mol) Cl-C-H 107 Cl-C-C 118 H-C-C 124

Upon optimisation using the Hartree-Fock method and STO-3G basis set, the geometry of the molecule changed Cl-C-H 109 Cl-C-C 122 H-C-C 124

Bond lengths remained unchanged (to nearest .1 angstrom).

| HOMO-1 | HOMO | LUMO | LUMO+1 | LUMO+2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

After submitting both the diene and its HF/STO-3G optimised monohydrogenated analogue for vibrational analysis.

| C-C stretch (exo) | C-C stretch (endo) | C-Cl stretch | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorodiene[9] | 1740.8  |

1760.9  |

772.6  |

| Exo-Hydrogenated chloroalkene[10] | N/A | 1761.7 | 776.8 |

The C-Cl bond in the chlorodiene has a lower stretching frequency than that in the hydrogenated molecule. The orbital overlap of the exo- C=C π-bonding orbital and the C-Cl σ*-antibonding orbital causes a weakening of the C-Cl bond. This addition of electron density to the antibonding orbital weakens bond strength and reduces frequency of stretching vibration.

This donation of electron density also renders the exo- C=C double bond weaker, due to donation of electron density away from it. This manifests itself in the IR spectrum of the chlorodiene, as the endo double bond stretching frequency is higher than that of the exo double bond.

Mini-Project: The Securinega alkaloids

Introduction

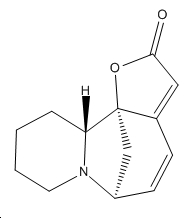

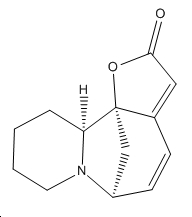

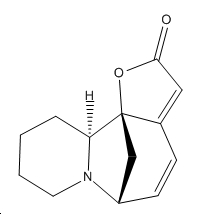

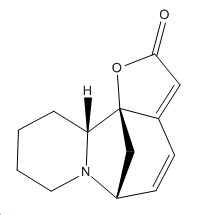

The Securinega alkaloids are a group of compounds which have a tetracyclic backbone. This class is divided into norsecurinine type alkaloids, containing a pyrrolidine fused ring[11], and securinine-type alkaloids, with a piperidine fused ring as shown below. It is this group of compounds which will be the focus of our study.

Securinine, the most common of the species was first isolated in Russia in 1959[12]. These compounds are known to hve biological activty, securinine is a GABA receptor antagonist[13]. This study largely concerns the first entantio and diastereoselective synthesis of allosecurinine by Leduc and Kerr, and the 2008 synthesis of securinine by Dhudshia and co-workers.[14]

Structures

| Securinine | Allosecurinine | Virosecurinine | Viroallosecurinine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D |  |

|

|

|

| 3D |

As can be seen, securinine and virosecurinine are enantiomers, as are allosecurinine and viroallosecurinine.

It can be seen that the piperidine rings of securinine and virosecurinine form chair structures, whereas allosecurinine and viroallosecurinine form more boat-like strucutres.

Proton NMR

Due to the inaccuracy of the method for the H nucleus, such data was not interpreted. Molecules of this type would have several peaks at similar shift so it was not worthwhile to analyse the data obtained.

Carbon NMR Analysis

In Leduc and Kerr's 2008 total synthesis of allosecurinine[15] the 13C NMR was not assigned, but peaks were recorded as follows: (100MHz, CDCl3): δ = 172.6, 167.5, 148.7, 122.6, 108.9, 91.7, 60.7, 58.8, 43.6, 42.7, 22.2, 21.0, 18.4

Whereas the calculated spectrum reads[16]: (CDCl3)δ = 166.5 (C3), 166.2 (C1), 152.9 (C5), 120.8 (C4), 106.3 (C2), 89.4 (C12), 60.4 (C11), 59.1 (C6), 44.6 (C13), 43.3 (C7), 24.0 (C8), 22.2 (C10), 20.1 (C9)

Whilst on the whole, the calculated spectrum seems to be a fairly good fit, it is notable that there is a peak at 172.6 in the observed spectrum, whereas the highest shift carbon in the calculated spectrum is 166.5. Due to the poor handling of carbonyl carbons by the computational methods used, it is necessary to implement a correction for the carbonyl carbon (C1). The recommended correction is as follows[17]:

δcorr = 0.96δcalc + 12.2.

This gives C1 a corrected value of 171.8, a much better fit to the lowest field carbon in the observed spectrum.

The synthesis of securinine by Dhudshia et al gave the following unassigned spectrum: 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ 173.49, 170.02, 140.13, 121.26, 104.87, 89.35. 62.84, 58.63, 48.59, 42.16, 27.13, 25.75, 24.37

The calculated spectrum of securinine reads[18]: 168.8 (C3), 167.2 (C1), 142.14 (C5), 119.2 (C4), 102.2 (C2), 87.1 (C12), 61.5 (C11), 59.0 (C6), 48.4 (C7), 44.5 (C13), 28.8 (C10), 27.4 (C8), 26.1 (C9) The corrected value for C1, calculated in the same method as previously, is 172.7ppm.

The two computational NMR calculations have shown a good fit with the NMR spectra of securinine and allosecurinine, and spectral assignments have been able to be made with a reasonable degree of certainty. For completeness and to reassure that correct configurations were obtained the NMRs of viroallosecurinine[19] and virosecurinine[20] were also run and, to great relief, to be identical to their respective enantiomers. Although the spectral differences between securinine and allosecurinine are not massive, the relative order of C10, C8 and C9 changes as a result of the orientation of the ring junction proton and methylene bridge. Likewise C13 and C7 change in order.

However, 13C NMR can offer no answers as to whether the compound synthesised is indeed say securinine, or its enantiomer virosecurinine. For this, it is necessary to calculate optical rotation.

Optical Rotation

The NMR output file was then subjected to an optical rotation calculation. This is a long calculation which, due to the vast number of approximations necessary to make the calculation time-efficient, often only gives accuracies such that the absolute sign of the rotation is trustable. However, as the literature values for the optical rotations of these compounds were all large, it was deemed worthwhile. As can be seen, impressively accurate computational values were obtained, and it has been shown that in the syntheses of both securinine and allosecurinine, the authors managed to make the enantiomer they claimed.

Virosecurinine[21] +1037 Securinine[22] -1035 (experimental -1085) Allosecurinine[23] -1113 (experimental -946) Viroallosecurinine[24] +1070

IR Analysis

Computational vibrational analysis of the two diastereomers was made. In both cases it is obvious that by far the most intense stretch is that of the carbonyl. Whilst the carbonyl stretch of allosecurinine[25] is found to be at 1866 cm-1, and the securinine[26] carbonyl stretch 3 inverse centimetres higher at 1869 this is a minor difference that can not be interpreted due to the high errors associated with the calculation, especially at such high frequency.

Conclusions

Experience with the MM2 force field has most certainly been gained. Its strengths at predicting the energetically favourable conformations of organic molecules have been illustrated, as have its limitations in accounting for less conventional bonding types and heavier atoms. The ability of computational techniques using the Gaussian program to predict spectral data have been shown to be relatively successful in the case of the Securinega alkaloids, where a very rigid backbone enabled calculations to be conducted rapidly, as few conformations were possible.

Notes

- ↑ Gilchrist, T.L.; Storr, R.C. "Organic Reactions and Orbital Symmetry" 2nd ed. 1971, CUP Archive, p. 119

- ↑ Woodward, R.B.;Hoffmann,R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1969, 8, 781

- ↑ Herndon, W.C.; Hall, L.H. Tetrahedron Lett., 1967, 3095.

- ↑ Skala, D.; Hanika, J. Petroleum and Coal, 2003, 45, 105

- ↑ Leleu, S.; Papamicael, C.; Marsais, F.; Dupas, G.; Levacher, V. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919-3928. DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ Bredt, J.; Thouet, H.; Schnitz, J. Justus Liebigs Ann. 1924, 437, 1.

- ↑ Maier, W.F.; Schleyer, P.R. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891. DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ M. Fernandes, F. Fache, M. Rosen, P.-L. Nguyen, and D. E. Hansen, 'Rapid Cleavage of Unactivated, Unstrained Amide Bonds at Neutral pH', J. Org. Chem., 2008, 73, 6413–6416 ASAP: DOI:10.1021/jo800706y

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1622

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1707

- ↑ Kammler, R.; Polborn, K.; Wanner, K.T., Tetrahedron, 2003, 59, 3359 DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(03)00406-X

- ↑ V. I. Murav'eva, A. I. Ban'Bkovskii, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1956, 110, 998 – 1000

- ↑ Beutler, I.A.; Karbon, E.W.; Brubaker, A.N.; Malik, R.; Curtis, D.R.; Enna, S.J. Brain Res. 1985, 330, 135

- ↑ Dhudshia, B.; Cooper, B.T.F.; Macdonald, C.L.B.; Thadani, A.V. Chem. Comm. 2009, 463 DOI:10042/to-1666

- ↑ Leduc, A.B; Kerr, M.A., Agnew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 7945 DOI:10.1002/anie.200803257

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1665

- ↑ http://www.ch.ic.ac.uk/wiki/index.php/Mod:organic#Analyzing_the_NMR_Chemical_Shift_calculation

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1666

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1730

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1729

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1669

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1671

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1672

- ↑ Unable to publish to D-space

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1728

- ↑ DOI:10042/to-1727