Imprj:adamantane

Module 2 mini-project: Adamantane

This mini-project will focus on adamantane. Firstly, the optimised structure of the molecule will be analysed, with particular attention to the electron density distribution. Secondly, we will compare the adamantane with the four mono-substituted derivatives of adamantane. How does the presence of an EW or ED group affect the MOs and electronic density in the rings? How will this change the reactivity? How about the charge distribution, is that affected too?

Part 1 - The structure of Adamantane

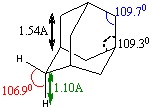

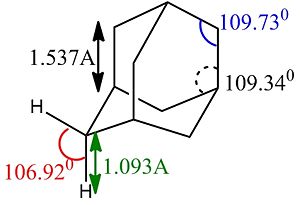

In order to maximise its precision, the optimisation of adamantane was carried out by using a good basis set (6-311G(d,p)) and the B3LYP method (http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5402). Being adamantane a common ring structure, its structure was already available and well-drawn in Gaussview, so the optimisation only brought to slight angular changes. The resulting structure appears with the following bond angles and lengths (left). A similar study by Korolkov and Sizova indicates the matching values on the right, confirming the validity of the optimisation method here adopted.[1]

|

|

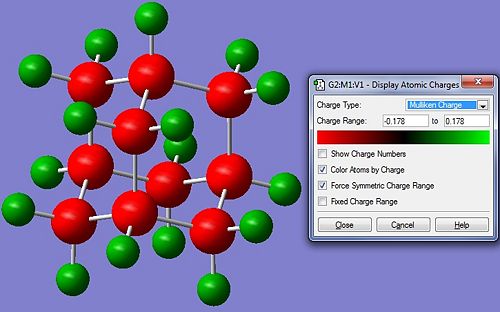

NBO analysis (files available at http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5445) reveals that the negative charge lies primarily on the carbons. This is unusual, as the C and the H have similar electronegativity, so they should have pretty much an even distribution of charge in the covalent bonds that join them. However, this is not what appears from the NBO analysis. This suggests that the carbons hold the electrons tighter than H and they probably are contributing more to the bond. When we look into the log file, in fact, we see that in all C-H bonds, about 60% of the electrons are contributed by C and the remaining 40% from the Hs. Moreover, The 60% C contribution comes from a hybridised sp3 orbital and the H contribution is obviously all s. So why do the Carbons keep more electronic density close to their nuclei? They have a higher degree of delocalisaton than the Hs, so they can bear better the electronic cloud.

|

|

Furthermore, vibrational analysis (files available at http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5465) shows us that the optimisation was achieved. However it is not a particularly good optimisation, as the low frequencies (from the .log file) go below -10cm-1, in fact as low as -26.7cm-1, and also they go above 10cm-1

Low frequencies --- -26.6699 -0.0005 0.0005 0.0007 26.5423 39.9613 Low frequencies --- 314.6679 318.1275 320.1835

Despite this, the calculation is acceptable as we have an order of magnitude difference between the high and low frequencies. The IR of adamantane is

| 3044, 3026 C-H stretches | 1497 C-H bending | 1117 C-C torsion | 974 C-C stretch | 972 C-C stretch | 971 C-C stretch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Literature IR values for adamantane not found (searched via Beilstein, Scifinder, Reaxys.com, but there is lack of time to search further).

MO analysis (files available at http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5445) allows us to achieve further insight of the reactivity of the molecule.

It is reported that, differently from most saturated hydrocarbons, adamantane is particularly reactive, especially in the presence of substituents (in particular at the 3-coordinate carbon). I suggest that this might be due to the presence of four 3-coordinated carbons, which are able to partially delocalise charges arising in reactions transition states and intermediates. In fact, doubly cationic adamantanes are relatively stable, due to "3D-aromaticity",. as suggested by Smith et al.[2].

In support of the delocalisation of the charges on the 3-substituted carbons, we can see from the molecular orbital diagram below and by the orbital representations that in case of an electron being removed from the HOMO orbital, the positive charge could be shifted to 2 other degenerate orbitals (HOMO-1, HOMO-2).

|

The HOMO and the LUMO are highlighted (Please ignore the lowest orbital highlighted: mistake!) Also, a note about energies. The HOMO orbitals (Hom, HOMO-1, HOMO-2) are degenerate. This leads to a high availability of electrons to participate in reactions and e.g. add substituents. Additionally, the HOMOs and also some of the lower energy orbitals shown appear to be mainly antibonding. Hence, removal of electron density for these orbitals should stabilise the molecule. The HOMOs-LUMO gap is of 0.29eV. The structure of the LUMO (below) is such that addition of electrons to this orbital loosens up the whole structure, being an overall slightly antibonding orbital. This again causes the monosubstituted derivatives (that follow this section) to be more reactive (hence, more useful for pharmaceutical/technological purposes) than the adamantane precursor.

A curious fact: upon further analysis of the MOs above, we can notice that, in the inner cavity of adamantane, the electronic density tends to be lower than along the C-C bonds. The reason for this lies in the localized nature of single σ bonds, which are the only substantial interactions present.[1].

Part 2 - Comparison of adamantane to substituted complexes

The following monosubstituted derivatives of adamantane have been analysed: Nitro-, hydroxy- and chloro-adamantane. All substituents are attached to the 3-coordinated carbon of the precursor. The optimisation, frequency analysis and population analysis for these monosubstituted species was carried out using the same criteria as for adamantane (B3LYP, 6311-G(d,p) and for the population analysis pop=(nbo,full)) as to allow comparison between the species.

Nitro-adamantane

The nitro group (NO2-) plays an electron withdrawing effect on the molecule, removing electron density close to the position of adamantane to which it is attached. This is because NO2 induces both a negative inductive effect and a negative resonance effect, pulling the electron density towards the positively charged nitrogen and the electronegative oxygens.

Optimisation files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5490; NBO/MO files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5489; Frequency analysis files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5498

I expect the additon of this group to slightly stabilise the structure of adamantane, removing electrons from the HOMO (which appears to be slightly antibonding), hence stabilising the overall structure.

Hydroxy-adamantane

The hydroxy group (OH-) is an electron donating group, as it can contribute electrons to adamantane by resonance of its lone pair of electrons on the oxygen. This effect overrides the negative inductive effect due to the electronegativity of the oxygen atom.

Optimisation files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5494; NBO/MO files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5493; Frequency analysis files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5500

I expect the addition of this group to destabilise the molecule, as the LUMO will be filled, loosening up the structure of the molecule and making it more reactive.

Chloro-adamantane

The Cl group (Cl-) has a negative inductive effect (electronegative element) combined with a positive resonance effect (lone pairs are avaialble). If we draw a parallel between adamantane and aromatic species, we can conclude that, similarly to those cases, Cl is overall electron withdrawing (as NO2). Hence, similar effects to NO2 are expected.

Optimisation files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5495; NBO/MO files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5496; Frequency analysis files: http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-5499

The resulting optimisation relative energies are

| Relative energy (kJ/mol) | |

|---|---|

| Adamantane | -999,850 |

| Nitro-adamantane | -1,564,400 |

| Hydroxy-adamantane | -1,223,650 |

| Chloro-adamantane | -2,232,870 |

Adamantane has the highest energy, hence this data suggests that all functional groups stabilise the molecule.

The vibrational analysis allows us to say that:

NO2 optimisation is acceptable but not very good. One order of magnitude difference between low and high frequencies.

Low frequencies --- -17.3118 0.0005 0.0007 0.0010 8.9318 23.8542 Low frequencies --- 36.0213 185.3376 191.8194

OH optimisation is acceptable but not very good. One order of magnitude difference between low and high frequencies.

Low frequencies --- -18.1903 -3.1942 -0.0010 -0.0008 -0.0005 24.6558 Low frequencies --- 263.3939 267.7926 302.4452

Cl optimisation is acceptable but not very good. One order of magnitude difference between low and high frequencies.

Low frequencies --- -23.0229 0.0018 0.0029 0.0032 19.8233 22.0239 Low frequencies --- 210.3479 211.2565 318.6566

The charges in adamantane are now:

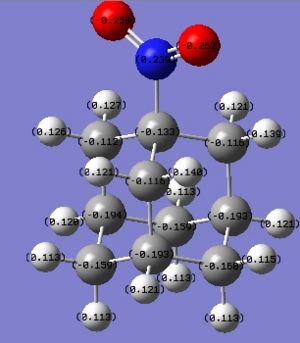

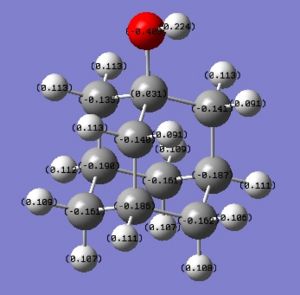

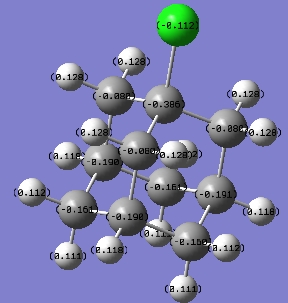

|

|

|

|

NO2 has rendered the whole ring more positive. As predicted, it has an EW effect.

OH has also rendered the whole ring more positive. In particular the carbon to which it is attached is way more positive than previously. An explanation for this fact could be that OH is able to Hydrogen bond to other Hydroxy-adamantanes. This fact could lead to the predominance of a negative inductive effect, as the LP of the O is now involved in the Hydrogen bond and is no more available for resonance.

Cl has made the 3-coordinate carbons more positive and all the 2-coordinate carbons more negative. An explanation to this could be that the electrons from the 3-coord.-Cs are withdrawn by Cl more from those atoms that are able to bear a more positive charge, as the 2-coord.-Cs are too unstable if electrons are take away from them.

In conclusion, the addition of substituents to adamantane brings to modifications in electronic density in the rings, allowing a higher degree of reactivity. Due to time constraints, a detailed vibrational and MO analysis is not possible, but the NBO analysis already gives an insight of the molecular reactivity.