Hoss.Module2

Inorganic Module 2: Ab initio and density functional molecular orbital

Hossay Abas

This report will use computational methods to analyse a series of inorganic compounds and obtain information regarding the structure and bonding, as well as spectral characteristics associated with each molecule. The techniques used will be used to compare the energies of stable conformers and can also be used to determine the presence of transition states.

Borane

Optimisation

Having drawn a planar structure of borane on Gaussview, the three B-H bond distances were changed to 1.50 Å, after which the structure was optimised.

The DFT-B3LYP method and the 3-21G basis set were used - these determine the type of approximations made when solving the Schrodinger equation and the accuracy involved in the calculation respectively. One way of checking that an optimisation has been carried out successfully is to look at the value for the RMS gradient; a successful optimisation will have a value lower than 0.001 (see below). Another way of checking would be to analyse the output file to see if the job had converged. This was found to be the case.

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | 3-21G |

| E(RB+HF+LYP) | -26.46226438 a.u |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.000000285 a.u |

| Point group | D3H |

After the optimisation step, the B-H bond lengths were all found to be 1.91 Å, this is very close to the literature value[1] of 1.95 Å; the slight difference is perhaps due to the errors associated with the computational calculation. Furthermore, the bond angles were all 120οC - this is consistent with the trigonal planar geometry of borane.

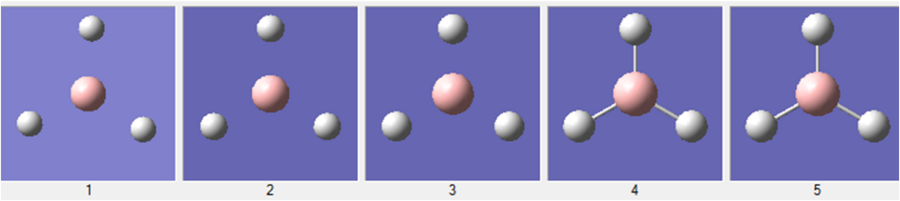

Whilst the molecule is undergoing optimisation, the potential energy surface is scanned in order to find the geometry with the lowest energy and RMS gradient. Each optimisation step reduces the energy with the final step approaching a value close to zero. The geometries of each individual optimisation step can also be captured on gaussview and is shown below:

This process can be displayed on a graph:

MO Analysis

Borane MO Analysis

Using the optimised structure from before, the molecular orbitals for borane were obtained and compared with the qualitative LCAO picture:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Molecular Orbital | Energy (hartrees) |

|---|---|

| HOMO-3 | -6.73049 |

| HOMO-2 | -0.51765 |

| HOMO-1 | -0.35681 |

| HOMO | -0.35681 |

| LUMO | -0.07458 |

| LUMO+1 | 0.18859 |

| LUMO+2 | 0.18859 |

| LUMO+3 | 0.19191 |

Comparing the MO's derived computationally with the theoretically LCAO proposed MO’s, it appears that there is a reasonably good match. The computationally determined results above indicate that there are two pairs of degenerate orbitals – this is also the case on the qualitative MO diagram. Visually, the computerised method provides a clearer picture as it merges together the lobes of overlapping orbitals. One can conclude that the qualitative method is a useful and quick approach to determining the molecular orbitals of simple complexes, however, in order to obtain a clearer idea of the energy differences between the various MO’s, the computational approach would be necessary. This technique also has the advantage in that it gives the size and shape of the MO's formed, something which the LCAO cannot do (as it only gives relative structures).

The three MO’s with the highest energy, of which two are degenerate, have very similar energies (0.191 and 0.188 Hartrees) – therefore, without the quantitative information obtained from the MO analysis above, it would be very difficult to qualitatively place the 2e’ and 3a1’ MO’s in the correct positions relative to each other – i.e. LCAO cannot accurately predict which of these is the more stable. The stability of the 2e’ degenerate MO’s over the 3a1’ MO can perhaps be explained by considering that there are greater anti-bonding interactions in the latter case.

A further limit of the LCAO approach is that predicting the MO diagram for complex molecules consisting of more atoms becomes increasingly difficult and time consuming.

NBO Analysis

NBO analysis provides us with information regarding regions of high and low electron density in the molecule. The charge distribution was assigned and can be illustrated using different colours, whereby red is indicative of high negative charge and green is indicative of high positive charge.

The diagram clearly shows that there is a region of high positive charge on the boron atom. This comes as no surprise considering the electron deficient nature of the B atom in the BH3 molecule. The total charge of the molecule is 0 as is expected for neutral borane. The NBO results also show that there are three boron-hydrogen bonding orbitals. Each of these B-H bonds have two electrons; the bonding orbital of boron consists of 1s and 2p orbitals i.e. it is an sp2 hybridised orbital and consists of 33.3% s character and 66.67% p character. This information can be found under the NBO section in the log file. In the case of borane, there are no interactions between the NBO’s and other orbitals, thus ruling out the possibility of secondary interactions - this is confirmed by looking at the log file under the section 'Second Order Perturbation Theory Analysis' - the very small value in the energy column suggests there are no interactions. Finally, the B hybrid orbitals contribute 44.49% of the B-H bond, the s orbitals on the hydrogen are responsible for the remaining 55.51% - this further explains why the electron density is distorted towards the hydrogen atoms.

Frequency Analysis

The optimised structure obtained was also used to carry out a frequency analysis; the same method and basis set as before were used, however this time “pop=(full,nbo) was inserted in the additional keywords section. A frequency analysis can be used to determine whether the optimised structure obtained in the previous step is truly the ground state configuration. The fact that all the frequency values were positive indicated that the optimisation was successful and confirmed that the optimised structure was indeed at an energy minima. Had there been a negative frequency value - this would indicate the presence of a transition state, and if there were more than just one negative frequency, this would imply that the optimisation had been unsuccessful as no critical point was found. This analysis can also be used to predict the vibrational frequencies of a molecule (i.e. the IR spectra):

| Vibration No. | Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Symmetry of D3h point group |

| 1 |  |

1146 | 93 | a2 |

| 2 |  |

1205 | 12 | e' |

| 3 |  |

1205 | 12 | e' |

| 4 |  |

2593 | 0 | a1' |

| 5 |  |

2731 | 104 | e' |

| 6 |  |

2731 | 104 | e' |

There were a total of 6 vibrations, this is as expected from the 3n-6 rule for a non-linear molecule (where n =4 for borane). The IR spectra shown below only shows 3 peaks – this can be rationalised by considering that there are two sets of degenerate frequency values (occurring at 1204.66cm-1 and 2731 31cm-1). As well as this, one of the vibrations is IR inactive (corresponding to a frequency of 2592.79cm-1) as the vibration is totally symmetric vibration and thus there is no overall change in the dipole moment.

It is worth noting that there are errors associated with these calculations and that these errors are expected to be larger for the higher frequency vibrations. This is because Gaussian does not consider the possibility of anharmonicity and its contribution to the frequencies.

Thalium Bromide

Optimisation

When optimising the geometry of thallium bromide, its symmetry was confined to the D3h point group in order to maintain this particular geometry. Unlike with the case of borane, a pseudo potential basis set was used as this takes into account the larger atoms used. The pseudo potential used in this example also considers the valence electrons involved in the bonding. The DFT-B3LYP method and the LANL2DZ basis set were used in the optimisation.

| File type | .log |

| Calculation type | FOPT |

| Calculation method | RB3LYP |

| Basis set | LANL2DZ |

| E(RB+HF+LYP) | -91.21812851 a.u |

| RMS Gradient Norm | 0.000000090 a.u |

| Point group | D3H |

Frequency Analysis

Thalium Bromide Frequency Analysis

Analysing the log file obtained from the frequency analysis can prove whether or not the TlBr3 molecule was successfully optimised. The important section that needs to be considered is the ‘low frequencies’ part in the log file which has been reproduced below:

| Low frequencies (cm-1) | -3.4226 | -0.0026 | -0.0004 | 0.0015 | 3.9361 | 3.9361 |

| "Real" normal frequencies (cm-1) | 46.4288 | 46.4291 | 52.1449 |

The first line relates to the 6 degrees of freedom accessible to the molecule, the second line corresponds to the real frequencies that the molecule exhibits.

The Tl-Br bond lengths were all found to be 2.65 Å and the Br-Tl-Br bond angles were all 120oC. These values are in good agreement of the literature values[2] (2.52 Å and 120oC for length and angle respectively). Although not exactly the same, the values are very close suggesting that the computational technique has yielded fairly accurate results.

The IR spectra for this molecule showed only three peaks - this is due to the fact that there are two sets of degenrate peaks. Also, one of the vibrations is IR active as it involves no change in dipole moment and is thus not observed on the spectra. Comparisons can be made to the vibrational spectra of the BH3 molecule which also showed three peaks. The similarity observed can be explained by appreciating that the point group for both complexes are the same (D3h). The difference between the spectra's for the two complexes is that the peaks appear at very different frequencies - for the boron complex the three peaks occur between 1000 and 3000 cm-1, whereas for the thallium complex, these peaks occur between 40 and 220 cm-1. This large difference can be attributed to the fact that the boron hydrogen bonds are a lot shorter and the atoms involved are smaller in mass; as there is an inverse relationship between frequency and mass, the spectra for borane occurs at much higher frequencies.

A bond can be defined as an attraction between two (or more) atoms which subsequently leads to a more stable arrangement. The atoms involved must have the correct orbital symmetry and have similar energies for effective overlap. One can consider a bond to be formed when atomic orbitals overlap to form molecular orbitals. Even though such interactions are actually spread throughout the molecule, it is a very useful to portray structures using bonds. In some cases, when Gaussview optimises a molecule, a bond may 'disappear' even though it is still there (i.e. the two atoms still share the electrostatic attraction). Gaussview draws bonds based on parameters for electronic interactions; if two atoms are a sufficient distance away from each other and exceed these defined parameters, the bond will no longer show.

Isomers of Mo(CO)4L2

Optimisation

The stability and spectral information of Mo(CO)4(Cl)2 will be examined. The results of this investigation can be used for describing complexes involving larger ligands which share similar electronic properties but which would be too time consuming using the methods described here, for example where L is PPh3. The cis and trans isomers of Mo(CO)4(Cl)2 were initially drawn on Gaussview and optimised using the DFT-B3LYP method and the LANL2MB basis set. The phrase opt=loose was then typed into the additional keywords section. The results from the firs optimisation are as follows:

|

|

The diagrams above show that the P-Cl bonds have disappeared following this optimisation – this is due to the pre-programmed definition of a bond on Gaussview (mentioned earlier). The psuedo potential LANL2MB has only provided us with a rough geometry and so the molecules were optimised further. Before the second optimisation was carried out, the isomers were altered slightly; for the cis isomer one of the P-Cl bonds was orientated such that it was parallel to one of the Mo-CO bond, while another P-Cl bond (from the other PCl3 group) was placed parallel to another Mo-CO bond:

For this optimisation, the LANL2DZ basis set was used and int=ultrafine scf=cover=9 was typed in the additional keywords section. The LANL2DZ basis set is much more accurate and has a better pseudo-potential with a tighter convergence criteria.

|

|

The energies for each isomer using the two different optimisation methods are summarised below:

| Isomer | 1st Optimisation - Energy (a.u) | 2nd Optimisation Energy (a.u) |

|---|---|---|

| cis | -617.525 | -623.577 |

| trans | -617.522 | -623.576 |

The second optimisation successfully reduced the energy of the isomers.

| Molecule | ΔE, KJ mol-1 (cis-trans) |

|---|---|

| Mo(CO)4(PCl3)2 | -2.73 |

| Mo(CO)4(PPh3)2 | -72.98 |

Overall both the computational determined values and the literature values[3] have the cis isomer as the more stable, though the computationally determined value is very small. It should be noted that the literature value corresponds to the molybdenum complex involving triphenylphosphine and not chlorine as the ligand, and therefore steric hindrance will play more of a significant role in the energies. The stability of the cis isomer can be explained by considering the trans effect; this is the labilization of ligands which are orientated trans to certain other ligands[4]. CO ligands are strong π acceptors and therefore have a strong trans effect. As a result, the Molybdenum complex would prefer to orientate the ligands in such a way as to avoid two CO ligands being trans to one another – thus the cis conformer is the more stable.

Geometric Parameters

| Cis Complex | Bond Length (Å) | Literature Value[5] | Trans Complex | Bond Length (Å) | Literature value[5] | |

| P-Mo | 2.51 | 2.58 | P-Mo | 2.44 | 2.50 |

| Cis Complex | Angle (o) | Literature Value[5] | Trans Complex | Angle (o) | Literature value[5] | |

| P-Mo-P | 94.2 | 104.6 | P-Mo-P | 177.4 | 180 |

The differences between the experimentally determined and literature values is again due to fact that different ligands are being used, however it is important to note that the values are within the correct range. The PPh3 ligand not only occupied more space but has more electron density and hence there are greater electronic repulsions taking place. This argument can be used to explain why the angles are slightly greater for this complex.

Frequency Analysis (using LANL2DZ)

Cis Frequency Analysis, Trans Frequency Analysis

The vibrational frequencies were determined from the LANL2DZ optimised geometries. The lowest frequencies for the vibrations along with diagrams depicting these vibrations are shown below:

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

|

10.87 | 0.0264 |

|

17.66 | 0.0074 |

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity |

|

4.80 | 0.0941 |

|

6.11 | 0.0000 |

These low frequency vibrations correspond to rotation of the Cl atoms around the P and Mo centre. The energy required to rotate this bond is very small, and taking into account the fact that the frequency associated with thermal energy at room temperature is close to 205cm-1, this means that these rotations could easily take place at room temperature.

The stretching frequencies for the CO vibrations are shown below:

| Symmetry | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency - Mo(CO)4PCl3[6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| B2 | 1945 | 763 | 1986 |

| B1 | 1949 | 1498 | 1994 |

| A1 | 1958 | 632 | 2004 |

| A1 | 2023 | 598 | 2072 |

| Symmetry | Frequency cm-1 | Intensity | Literature Frequency - Mo(CO)4PCl3[6] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eu | 1951 | 1475 | 1896 |

| Eu | 1951 | 1467 | 1896 |

| B1g | 1977 | 1 | |

| A1g | 2031 | 4 |

Although all of the carbonyl peak are within the correct range, the values differ quite a bit from the literature value. This is due to limitations and errors associated with the computational technique. One such limitation is that computational calculations do not consider the possibility of backbonding from the metal centre to the π* orbital of the carbonyl ligand (particularly in the case for the trans isomer).

Overall, four peaks are observed in both spectra's - this is to be expected in the case for the cis isomer but not for the trans. The trans isomer has D4h symmetry, whereas the cis isomer has C2v symmetry; as a result, in the trans isomer there are two stretches which are chemically equivalent and thus degenerate. Consequently, only one peak is observed for this stretch. The two highest frequency peaks for the trans isomer have very low intensities- this is not surprising considering the highly symmetric nature of this complex. On the other hand, the cis isomer does not experience this chemically equivalency, which results in two distinct peaks.

|

|

Mini Project

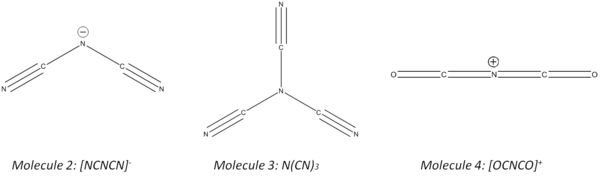

This mini project will focus on the structures and properties of [NCNCN]-, [N(CN)3], and [OCNCO]+. The effects of changing one of the atoms from nitrogen to oxygen as well as adding an extra cyano group will be investigated. The charge density and bonding modes differ for all three structures and will no doubt lead to different spectral characteristics. This investigation will use the methods employed above i.e. the molecules will initially be optimised and then the vibratonal frequency, moleular orbitals and NBO's will be examined.

Geometry Optimisation

The molecules were all initially drawn on Gaussview and optimised using the DFT-B3LYP method and the 3-21G basis set. Opt=loose was inserted into the additional keywords area. This rough optimisation is useful due to the very short amount of time required for the calculations. Since the molecules under consideration are relatively small, they were all further optimised using the more accurate LANL2DZ basis set (and the same method as before).

|

|

|

| Molecule | Symmetry | Energy (a.u) - 1st Opt | Energy (a.u) - 2nd Opt |

| 2 | C2v | -239.14 | -240.44 |

| 3 | D3h | -331.36 | -333.11 |

| 4 | D∞h | -279.51 | -281.00 |

For all three molecules, the second optimisation had further reduced the energy of the molecule and resulted in an even more stable state. These optimised structures were used for the remainder of the analysis.

Geometry Parameters

The bond lengths and angles of the optimised geometries were then obtained and compared with that of literature. [7]

| Bond | Bond Length (Å) | Literature Bond Length (Å) |

| CN (triple) | 1.20 | 1.14 |

| C-N | 1.31 | 1.47 |

| Bond | Bond Length (Å) | Literature Bond Length (Å) |

| CN (triple) | 1.18 | 1.14 |

| C-N | 1.38 | 1.47 |

| Bond | Bond Length (Å) | Literature Bond Length (Å) |

| C=O | 1.16 | 1.23 |

| C=N | 1.23 | 1.28 |

The bond lengths all match reasonably well with the literature values. It is clear that on going from a single to double to triple bond, the bond lengths shorten. Single bonds are a result of head to head overlap of orbitals (e.g. H2) – which result in sigma bonds. Double bonds on other hand involve sp2 hypridised orbitals i.e. 1 s and 2 p orbitals mix yielding three identical orbitals, this leaves behind an unhybridised p orbital. The sp2 orbitals overlap as before to form a sigma bond, but now the left over p orbital can overlap to form a π bond. Thus, the reason why double bonds are shorter than single bonds is because the atoms needs to be close enough for these unhybridised p orbitals to overlap. This argument extends to the case for the triple bond, which involve sp hybridised orbitals as well as two π components to the bonding. The values also indicate that the C=O bond is shorter than the C=N bond, this is due to the higher electronegativity of oxygen relative to nitrogen.

Frequency Analysis

[Molecule 2 Frequency Analysis], [Molecule 3 Frequency Analysis], [Molecule 4 Frequency Analysis]

Frequency calculations were carried out on the optimised structures using the B3LYP method and the LANL2DZ basis set. The molecules considered contain bonds commonly found in organic compounds and which show very characteristic (and usually) sharp peaks. Thus, looking at the IR spectra alone should be sufficient enough to distinguish between the three molecules.

Since IR spectroscopy is based on the change in dipole moments and since this change will be rather small in molecules containing high symmetry, it is expected that most of the intensities for the peaks would be quite low for the three molecules studied in this section.

The results for the vibrational analysis on molecule 2 is shown below:

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Description |

|

2217 | 1411 | Assymmetric CN (triple) stretch |

|

2192 | 78 | Symmetric CN (triple) stretch |

|

1407 | 46 | C-N Stretch |

The asymmetric C=-N stretch involves the greatest change in dipole moment, hence this peak has the greatest intensity and is responsible for the very sharp peak observed in the IR Spectra. Taking into account the small size and high symmetry of the molecule, it comes as no surprise that the IR spectra shows only one peak.

Frequency analysis can be used to investigate what effect adding an extra cyano group would have on the amine considered previously(i.e. going from molecule 2 to molecule 3). The addition of this extra group results in a complex which is even more symmetric than before. One would therefore expect the analysis to show degenerate stretches with lower intensities as the change in dipole moment will not be as significant.

The greatest change in dipole moment occurs for the symmetric CN stretch which has the highest intensity overall. As expected, the intensities are a lot smaller than in the previous case, specifically the peaks corresponding to the CN (triple) stretches. It should also be noted that the peak for the CN (triple) stretches, both asymmetric and symmetric, occur at a higher frequency for this molecule. This indicates that the triple bonds in this complex are stronger.

Frequency analysis of molecule 4 can be used to examine both the effects of changing the nitrogen to an oxygen as well as to see what effect going from a single CN bond to a double CN bond will have.

| Vibration | Frequency (cm-1) | Intensity | Description |

| 2534 | 2019 | Asymmetric N=C=O stretch | |

| 2372 | 0 | Symmetric N=C=O stretch | |

|

611 | 102 | N=C=O bend - degenerate |

The N=C=O bending peak is not present in the other spectra’s – thus allowing us to easily distinguish between this molecule and the other two. The other intensities are all close to 0, this again re-iterates the fact that the molecule exhibits a high degree of symmetry.

MO Analysis

[Molecule 2 MO Analysis], [Molecule 3 MO Analysis], [Molecule 4 MO Analysis]

The molecular orbitals were calculated using the optimised structure and DFT-B3lYP method. "Full NBO" option was selected under the NBO tab and the phrase "pop=full" was typed in the additional key words. The HOMO and LUMO for each of the molecules are shown below:

All of the MO’s are highly symmetrical as is expected. In all cases, there is clearly an increase in the number of nodes when moving from the HOMO to the LUMO, which indicates that there is an increase in anti-bonding character. The first two molecules, which contain triple bonds, have significant π orbital character across the CN bonds. It should also be noted that the greatest number of nodes are found on or around the carbon atoms and not on the electronegative N or O atoms. In the LUMO's for all three molecules, there was no contribution from the central nitrogen atom. This indicate that the nitrogen will not be involved in any LUMO based reactions. The HOMO and LUMO for [NCNCN]- and [OCNCO]+ can be further compared to one another; the LUMO for both molecules are nearly identical, and shows that upon moving from a bent structure to a linear structure, there is no real effect on this MO. On the other hand, the HOMO differs between the two and is due to there being a different number of electrons present in each molecule.

The bent geometry of molecule 2 can be rationalised by consideration of the HOMO-1 MO shown below:

This MO shows that upon bending, the bonding interactions between the two end orbitals increase thus leading to a more stable orientation. There is also a reduction in anti-bonding character between the central nitrogen and the two carbons either side of it.

NBO Analysis

An NBO analysis was carried out on the optimised structures in order to investigate the charge distribution:

[Molecule 2 NBO], [Molecule 3 NBO], [Molecule 4 NBO]

| Molecule | NBO |

|---|---|

| (1) [NCNCN}- |

|

| (2) [N(CN)3] |

|

| (3) [OCNCO}+ |

|

For molecule 2, the greatest electron density is on the central nitrogen atom; this is expected as there is a negative charge localised on this atom. The two carbons are surrounded by two electronegative nitrogen atoms and thus explain the region of positive charge density on these atoms (indicated by the bright green colour). Adding an extra CN group on to this nitrogen (i.e. going from molecule 2 to molecule 3) is expected to reduce the charge density on the central nitrogen atom. This can be rationalised by considering that CN is an electron withdrawing group. hence, the addition of another CN pulls some of the electron density from the central nitrogen. The NBO analysis also shows that this molecule is neutral overall. In molecule 3, the two carbon atoms have even more positive charge density than in the previous two cases; this can be attributed to the fact that it is now surrounded by a N and an O atom; since O is even more electronegative than N, there is an even greater pull of electron density away from the carbon centre.

NB: the out.log files were used to analyse the NBO’s whereas everything beforehand was analysed using the formatted checkpoint file. The structures from the two outputs differed slightly.

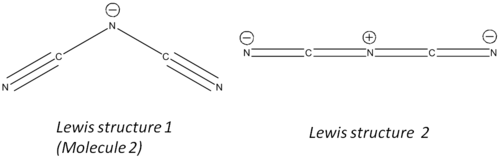

Further Analysis on the structure of [C2N3]-

Two lewis structures have been proposed for the [C2N3]- molecule[8] (one of which is shown above (molecule 2)):

[Lewis Structure 2 Optimisation],[Lewis Structure 2 Frequency Analysis]

Analysis of the structure showed that Lewis Structure 1 had the correct structure. This is because having optimised both molecules and carrying out a frequency analysis, the results for Lewis Structure 2 came back with negative vibrational frequencies. As mentioned earlier, this means that the structure did not successfully optimise, which in turn means that Lewis Structure 2 cannot be the correct form.

Conclusion

The computational analysis on the three molecules have prooved to be useful in distinguishing between them. The values obtained for the bond lengths matched well with the literature values and the vibrational frequencies showed the characteristic peaks for the various bonds considered. MO and NBO analysis also gave a good indication of the charge distribution. Finally, frequency analysis helped in confirming the correct lewis structure for the [C2N3]- molecule.

N.B: The errors associated with the values has already been defined by Gaussview: the values for energy have an error of -10 kJmol-1, the frequency values have an error of approximately 10% (as anharmonicity is not accounted for); bond lengths and angles have errors of approximately 0.01 A and 0.1o respectively.

References

- ↑ Kawaguchi, K, 'J.Chem.Phys, 1992 , 96 (5), 3411

- ↑ J Blixt, J Glaser, J Mink, I Persson, P Persson and M Sandstrom, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 1995, 117, 5089-5104

- ↑ . W. Bennett, T. A. Siddiquee, D. T. Haworth, S. E. Kabir and F. Camellia, 'J.Chem.Cryst, ‘’’2004 ‘’’, ‘’34 (6)’’, 353-359

- ↑ . Coe, B. J.; Glenwright, S. J., 'Co-ord.Chem.Rev, ‘’’2000 ‘’’, ‘’203’’, 5-80

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 G. Hogarth, T. Norman, Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1997, 254, 167-171

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Elmer C. Alyea and Shuquan Song, Inorg. Chem., 1995, 34, 3864-3873

- ↑ F. H. Allen, O. Kennard, D. G. Watson, L. Brammer, A. G. Orpen., J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans., 1987, II, S1-S19

- ↑ Housecroft. C. E, Sharpe. A. G, 'Inorganic Chemistry', 3rd edition, pg 412-413