Hoss.Module1

Aims and Introduction

Computational techniques are commonly used to analyse the structure of (mainly) organic structures, and this area of research is vastly growing. This method avoids trying to solve the Schrödinger equation as it only considers individual bonds and thus is less time consuming. This report will make use of MM2 and MMFF94 force fields and MOPAC/PM6 (a semi-empirical molecular orbital model). The DFT method will also be used (in Gaussian). The main aim of this module is to use molecular mechanics to predict the stereo and regio selectivity for a range of organic molecules.

The Hydrogenation of Cyclopentadiene Dimer

Dimerisation and Selectivity

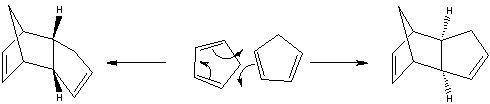

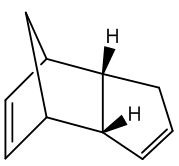

Cyclopentadiene undergoes a dimerisation reaction in a [π 4 s + π 2 s] Diels-Alder cycloaddition, which proceeds via a 6 membered ring transition state. In this reaction, the dimerisation results in the endo form rather than the exo form. The two conformers are shown below:

|

|

In such Diels-Alder reactions, if the reaction proceeds under kinetic control then the endo product usually forms exclusively over the exo form. Since this reaction is irreversible, the endo product dominates and hence it can be concluded that the dimerisation of cyclopentadiene is kinetically controlled. Woodward and Hoffmann believed that the reason for this lied in the interactions which take place between the occupied and unoccupied orbitals. Investigation of the transition states showed that orbital symmetry favours the endo conformer over the exo conformer. [1] Applying the MM2 method to determine the total energies showed that the exo conformer was the more stable. Thus, it can be said that the exo form is the product of thermodynamic control, and the endo form is the product of kinetic control.

| Dimer | Total Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Exo | 31.8785 |

| Endo | 34.0012 |

Consideration of transition states and resonance structures can also be used to explain the selectivity observed. The transition state in an asynchronous mechanism can be described using several resonance structures, one of which resembles a zwitterion for each adduct; in the case of the endo transition state, the proximity of the two charges stabilizes this structure and favours its formation. Studies have found that following the cycloaddition of the two cyclopentadienes, the forming bond lengths are 2.183 Å and 2.119 Å in the exo transition state and 2.184 Å and 2.127 Å in the endo transition state[2], this provides proof for the asynchronous mechanism, and also shows that the endo transition state is more assymetric, i.e. the zwitterion resonance structure for the endo structure is more favourable.

The preference for the endo product is an example of the "endo rule" of Diels-Alder reactions, whereby the endo product is kinetically preferred and the exo kinetically preferred. Note that in some reactions, the kinetic and thermodynamic product might be the same.

Hydrogenation of the Dimer

Hydrogenation of the endo adduct initially yields the dihydro derivative (4) as opposed to the dihydro derivative (3). Only after prolonged periods will the tetrahydro product be favoured. This is supported by the MM2 calculated energies:

|

|

| Relative Contributions | Molecule (3) (Energy kcal/mol) | Molecule (4) (Energy kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Stretch | 1.2279 | 1.1366 |

| Bend | 18.6932 | 13.0252 |

| Torsion | 12.8241 | 12.4289 |

| 1, 4 VDW | 6.0390 | 4.4279 |

| Total Enegry | 36.8666 | 29.2548 |

The values indicate that (4) is the thermodynamically more stable product of hydrogenation. Closer inspection of the values shows that the greatest contribution to this difference comes from the bending mode. Molecule (3) has a norbornene doule bond whereas molecule (4) has a cyclopentene; the norbernene double bond is weaker and longer than that of the cyclopentene[3], thus explaining why molecule (4) is preferred.

Stereochemistry of Nucleophilic Additions to a Pyridinium Ring (NAD+ analogue)

Reaction of a Pyridinium Ring with a Grignard Reagent

The optically active derivative of prolinol molecule (5) is able to react with grignard reagents such as methyl magnesium iodide to alkylate the pyridine ring at the 4-position. The product has the absolute stereochemistry as shown in molecule (6). The mechanism involves the nucleophilic methyl group of the grignard reagent attacking at the 4 position of the pyridinium ring (i.e. para to the methyl substituent):

In order to determine the most stable form of molecule (5), various conformations were optimised and the variational principle was then applied (i.e. lowest energy is the most stable). The starting points differed in several different ways; on some occasions the 5 and 7 membered rings were significantly distorted, other times the carbonyl was moved into a position where it would have an anti-periplanar interaction with the nitrogen lone pair. The results from three of the starting points (including the most stable conformation) are shown below. Since the carbonyl centre was involved in the mechanism, the dihedral angle between the carbonyl centre and the C-4 carbon on the aromatic pyridine ring were also computed.

| Conformer | Energy (kcal/mol) | Dihedral Angle (o) |

|---|---|---|

|

43.1034 | 10.1433 |

|

44.0836 | 14.7396 |

|

268.4467 | 55.7756 |

In all cases, the carbonyl group is situated above the plane of the aromatic ring. As shown in the mechanism, this carbonyl group interacts with the magnesium, and thus the grignard reagent attacks the pyridinium ring from above the plane. It is evident that the MM2 calculations resulted in accurate predictions regarding the regio and stereoselectivity observed. Aside from the change in the above mentioned dihedral angle, the main differences between the conformers above are the steric congestion within the ring systems. The third conformer has a severely distorted 7 membered ring, explaining its remarkably high energy.

It should be noted that when determining the total energy of the structure, one cannot include the MeMgI grignard compound for MM2 minimisation, because this MM2 does not define the relevant parameters for the element Mg resulting in an error message.

Reaction of a Pydridinium Ring with Aniline

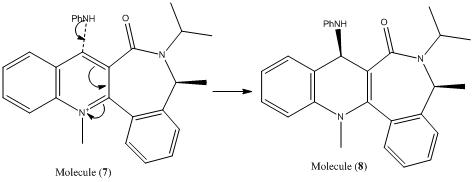

The nucleophilic addition of aniline to the pyridinium salt is also an example of a highly regio and stereoselective reaction.

In this reaction, the quinolinium salt, molecule (7), is attacked by a nucleophilic amine group in a selective manner to yield molecule (8). The selectivity observed in this reaction can be explained by consideration of the carbonlyl group's steric control on the conformer [4], whereby the nucleophile prefers to attack on the opposite side of the aromatic ring with respect to the carbonyl group. Another factor contributing to the stereo chemistry of the product is the repulsion experienced between the lone pairs on the nitrogen (of the incoming aniline) and the oxygen (of the carbonyl group).

| Most Stable Conformer of Molecule 7 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

This is supported by analysis of the dihedral angles and the corresponding total energy of the conformation, which were calculated on ChemBio3D.

| Molecule | Total Energy (kcal/mol) | Dihedral Angle (o) |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | 64.2478 | -25.8042 |

The model supports the above statement as the most stable conformer existed with the carbonyl group pointing approximately 25(o) below the pyridine ring; the amine does not attack at this position as it is electronically and sterically hindered by the carbonyl group – it instead attacks at the top face at the C-4 position. This result is consistent with the experimental observation by Leleu et al[4], which states that the steric control enforced by the C=O group results in the diastereofacial selectivity observed.

When attempting to discover the lowest energy conformation for the molecules in the reaction above, it was evident that there were many conformations that could be adopted (i.e. there wasn’t one single energy minima). Hence, using this type of approach to determine the most stable conformation has its disadvantages, however this may be overcome by the introduction of sterically bulky groups (like tetramethyl silane) leading to a conformationally rigid molecule. In these calculations the MM2 minimization method was used, in order to obtain more accurate results, MOPAC/PM6 or DFT/mpw1pw91 could have been used instead; these methods provide information about the electronic structure and molecular orbitals of molecules, ultimately producing more accurate conformations and energies.

Stereochemistry and Reactivity of an Intermediate in the Synthesis of Taxol

This section will focus on one of the key intermediates formed in the synthesis of taxol[5], a drug which is widely hailed as one of the most significant advances in cancer therapy[6]. The intermediate in question exists as atropisomers (molecule (9) and (10)) - this type of isomerism arises due to steric hindrance around the bonds preventing rotation. As such, the energy required to inter convert between the two structures is too high, a consequence of which is that both conformations are observed.[7]

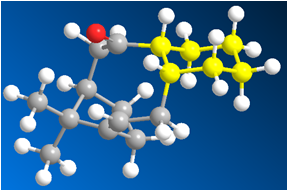

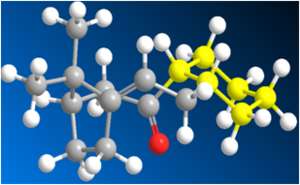

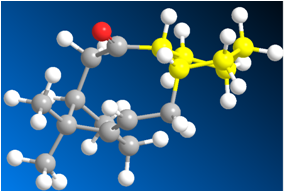

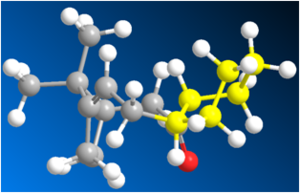

Studies have found that molecule (9) isomerises to molecule (10) if it is left to stand.[8]. The MM2 and MMFF94 method was used to deduce the total energy of each atropisomer:

Both methods indicate that isomer (10) (which has the carbonyl pointing down) is thermodynamically more stable, thus explaining why isomer (9) reverts to isomer (10) on standing. In order to achieve the lowest energy conformation, several starting points were tested - specifically the orientation of the cyclohexane ring was varied as this was found to have a significant effect on the energy. The energy diagram (shown on the right) clearly illustrates that the chair conformation of the cyclohexane ring is the most stable. This conformation was achieved for both isomers (9) and (10). The twist-boat conformation for both isomers were also found, and the corresponding energy associated with each showed, as expected, that the chair was the most stable. The values also indicated that the chair conformation for isomer (10) was lower in energy than the chair conformation for isomer (9).

| Isomer 9 | Isomer 10 | ||||||

|

|

Both isomers (9) and (10) react slowly to hydrogenation, which is unusual for strained alkenes; this lack of reactivity can be attributed to the cage structure of the molecule and the stability this provides. Such alkenes are known as 'hyperstable alkenes' and are less strained than the corresponding saturated hydrocarbon. In this example, the stability arises due to the bridgehead location of the double bonds. A hyperstable alkene is characterised by having a negative 'olefin-strain' (OS) energy - this is defined as the difference in the strain energy between the alkene and its parent hydrocarbon.[9] Another reason why the OS is negative for isomers (9) and (10) may be due to the fact that there are stabilising interactions between the hydrogens on the double bond.

Modelling using semi-empirical Molecular Orbital Theory

Molecular orbitals and reactivity

| Molecule 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

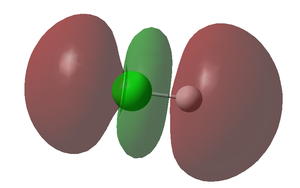

It is no secret that there are limitations with the molecular mechanics techniques used thus far, and it is therefore essential that one takes into account the electrons involved and its influence on the molecule’s properties. In this section, MM2 and MOPAC/PM6 will be implemented in order to minimise the energy and optimise the geometry of a molecule. It will also be used to calculate the molecular orbitals involved and the IR spectra of a chloro-compound (molecule (12)).

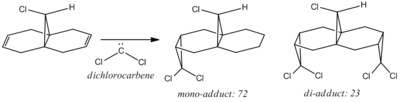

Halton et al observed that in the reaction between molecule (12) with an electrophilic reagent (dichlorocarbene), the mono-adduct predominately formed.[10]

High regioselectivity was observed in this reaction, with the exo double bond being the preferred site of attack. This observation can be rationalised by considering the molecular orbitals of the molecule in question (shown below):

|

|

|

|

|

The HOMO above clearly indicates that there is greater electron density at the syn alkene (i.e. the double bond on the same side as the chlorine atom) – hence this double bond is the more nucleophilic of the two. Thus, as demonstrated above in the reaction with dichlorocarbene, the syn double bond is selectively attacked by the electrophile. The HOMO also clearly shows that the area to be attacked is sterically accessible to the incoming electrophile. Turning our attention to the HOMO-1, it is evident that a greater share of the electron density resides at the anti alkene. The regioselectivity can be explained further by considering stereoelectronic effects. In molecule (12), stabilising anti-periplanar interactions exist between the σ* C-Cl orbital (LUMO+1) and the occupied π orbital of the anti alkene (HOMO-1) – as such this alkene is slightly stabilised with respect to the syn alkene.[11]

Vibrational (IR) Frequencies

In order to investigate the effect that the C-Cl bond has on the vibrational frequency, molecule (12) was compared to a mono-hydrogenated version whereby only the anti alkene double was replaced by a single bond.

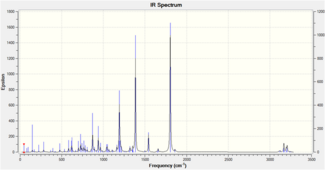

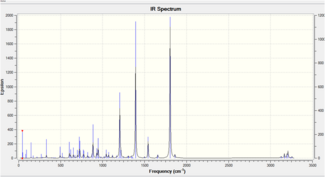

SCAN followed by Gaussview 5.0 were used to calculate the vibrational frequencies of both molecules:

| Bond | Molecule 12 | Hydrogenated Alkene |

|---|---|---|

| C-Cl stretch (cm-1) | 771 | 775 |

| Syn C=C stretch (cm-1) | 1757 | 1758 |

| Anti C=C stretch (cm-1) | 1737 |

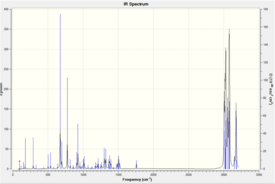

Below is shown the IR spectra for molecule 12[12], and the hydrogenated form[13].

|

|

The C-Cl stretching frequencies for both molecules are both consistent with literature values and lie between the expected range of 600-800-1.[14] On the other hand, the alkene stretches differ rather markedly from literature values (between 1620 and 1680-1). This difference may be due to limitations in the computational approach which carries out the calculations in the gas phase, whereas experimentally such values are determined in a liquid or solid phase.

The above values indicate that the syn double bond is stronger (as it has a higher vibrational wavenumber). The orbital mixing which arises from the anti-periplanar interaction between the σ* of the C-Cl bond and the π orbital also explains why the the C-Cl bond is weaker; the electron density is effectively being donated into an anti-bonding orbital. It is also evident that upon hydrogenation of the anti alkene, the vibrational frequency of the syn double bond doesn't really change - this is unsurprising as the molecule is not conjugated and hence no resonance contribution or other electronic effects are in play.

Further investigation can be carried out by altering the substituent on the anti alkene and analysing any electronic effects this may have on the C-Cl and C=C stretching frequencies. The =C-H group was changed to =C-OH, =C-CN, =C-BH2, =C-SiH3 and the following results were obtained:

| Derivative | C-Cl stretch | Syn-alkene stretch | Anti-alkene stretch |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule (12) | 771 | 1757 | 1737 |

| Molecule 12 Hydrogenated | 775 | 1758 | |

| OH Group | 765 | 1758 | 1753 |

| CN Group | 766 | 1757 | 1706 |

| BH2 | 759 | 1757 | 1657 |

| SiH3 | 765 | 1757 | 1690 |

The results clearly indicate that on replacing the hydrogen with one of the aforementioned groups, the stretching frequencies for the double bonds and the C-Cl bond changes. The stretching frequencies can all be rationalised by consideration of the electronics involved around the bonds in question. In the case of the OH group, the alcohol is an electron donating group and can donate electron density into the π* orbital of the anti alkene double bond. This would lead to a weakening of the alkene double bond, however the values above indicate that bond is strengthened. This can be explained by considering that the C=C-OH bond can undergo keto-enol tautomerism into the preferred C-C=O arrangement. Similar to the syn vs anti argument above, the filled C=O orbital can donate electron density into the σ* orbital of the C-Cl bond. This would also have the effect of reducing the strength of the C-Cl bond which is indeed observed. The cyano group on the other hand is an electron withdrawing group and thus pulls some of the electron density out of the anti double bond resulting in a weaker bond. For the case involving the silyl group, the electronegativity difference between silicon and carbon is rather small, and therefore it is perhaps better to focus on the orbital interactions to explain the weakening of the bonds. Silicon is in the second row of the periodic table and has available empty d orbitals which may interact with the occupied π orbital of the alkene, subsequently reducing some of the electron density on the double bond. This is further supported by the fact that the stretching frequency for the syn double bond is not that different from the unsubstituted molecule as there exists no such interactions. An alternative explanation may be that donor acceptor interactions exist between the silicon and the anti double bond. The table above shows that the greatest effect on the stretching frequency is observed when the BH2 group is substituted onto the alkene. This is as expected and can be explained by appreciating that the BH2 group is a lewis acid; the boron has an available p orbital, which combined with its electron deficient nature means that this group it is more than willing to accept electron density from the anti alkene.

Structure based mini-project using DFT-based molecular orbitals method

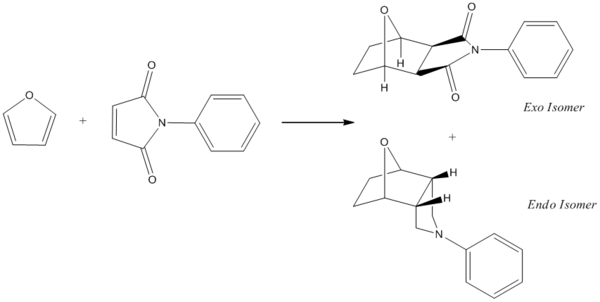

Overview of Reaction

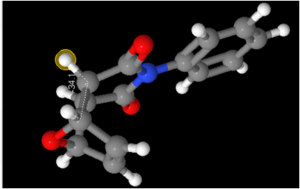

‘Endo- and Exo- stereochemistry in the Diels Alder Reaction’ has been chosen as the focus of the mini project. The reaction under investigation will be that between furan and N-phenylmaleimide resulting in an endo and exo form of 7-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptene, carried out by Cooley and Williams.[15] This ring system is conformationally rigid[15] and is thus ideal for the computational techniques which will be implemented in this module. If this reaction were to be carried out in a lab, the isomers could be separated using column chromatography.[15] The mechanism involved proceeds via a Diels-Alder [4 + 2] cycloaddition. Such reactions are particularly appealing for computational techniques as the mechanism is intrinsically interesting and is widely accessible at the undergraduate level.[16]

The above reaction is an example of the “endo rule” of the Diels-Alder reaction whereby the endo-adduct is the product of kinetic control and the exo-adduct is the product of thermodynamic control.[15] Cooley and Williams found that if the reaction was run for 7 days at 0 deg., the endo product was the preferred product, however as the reaction mixture was allowed to reach equilibrium over a period of 20 days (at an ambient temperature) the exo product became increasingly predominant.[16] It is commonplace for Diels-Alder cycloaddition reactions involving furan to proceed in a reversible manner - this is attributed to the heteroaromaticity of the furan.[16]

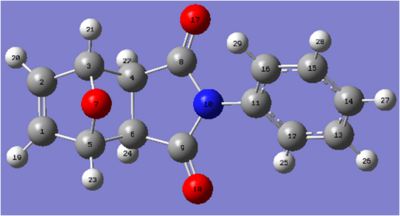

| Exo Isomer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

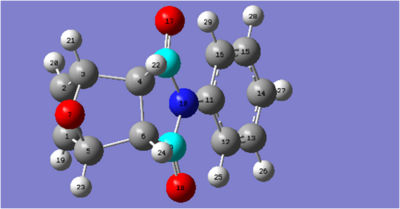

| Endo Isomer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

In the literature paper, the two isomers formed were differentiated by considering the NMR data. Specifically, investigation of the dihedral angle and subsequent use of the Karplus equation allowed for the determination of the stereochemistry. Computational methods will be used to calculate the 13C NMR; the 3J(H-H) coupling constants; and the IR stretching frequencies. The data obtained will then be compared with that of literature.

Both isomers were first drawn on ChemBio3D, after which the geometries were optimised using the MM2 force field. The values for the total energy is consistent with the exo isomer being the thermodynamically favoured isomer as it has a lower energy relative to the endo form.

| Molecule | Total Energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| Exo Isomer | 48.7178 |

| Endo Isomer | 50.5623 |

Analysis

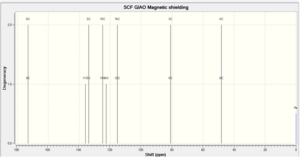

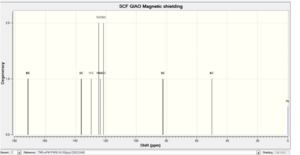

The isomers were optimised using the DFT/mpw1pw01 method and were then sent to SCAN to perform the initial geometry optimisation. Once completed, the isomers were then edited and sent to SCAN once more in order to perform NMR and IR calculations. The 13C NMR data was calculated for both the exo and endo isomers, and the values obtained were compared to literature.

| Peak | Carbon Number | Experimental[17] δ/ ppm | Literature δ/ ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,9 | 171.6 | 175.3 | |

| 2 | 1,2 | 136.4 | 136.7 | |

| 3 | 11 | 129.7 | 131.5 | |

| 4 | 13,15 | 124.7 | 129.1 | |

| 5 | 14 | 123.7 | 128.8 | |

| 6 | 16,12 | 121.5 | 126.5 | |

| 7 | 3,5 | 82.3 | 81.4 | |

| 8 | 6,4 | 50.0 | 47.5 |

| Peak | Carbon Number | Experimental[18] δ/ ppm | Literature δ/ ppm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,9 | 173.1 | 173.9 | |

| 2 | 11 | 136.03 | 134.6 | |

| 3 | 1,2 | 133.9 | 131.4 | |

| 4 | 15 | 124.8 | 129.2 | |

| 5 | 13,14 | 123.9 | 128.8 | |

| 6 | 12,16 | 119.9 | 126.3 | |

| 7 | 3,5 | 80.9 | 79.8 | |

| 8 | 4,6 | 48.2 | 45.9 |

|

|

Having analysed the 13C NMR, it appears that the computational methods used have achieved the same number of peaks in nearly the same environments. In both cases there were 8 clear peaks on the NMR; it was also the case that some of the carbon peaks overlapped with others, e.g. carbon 1 and carbon 2 are in a very similar chemical environment (they are not quite chemically equivalent but are very close). Due to the conformational rigidity of the isomers, it is no surprise that the computational method invoked did not produce more peaks then expected – if this were not the case, then one would expect a rather messy spectrum. Having said that, it is possible for the N-Ph bond to exist in different conformation – something which the computational method does not consider as it only takes frozen snapshots of the molecule.

Overall, the differences between the calculated and literature values are not too dissimilar. This can perhaps best be portrayed on a graph:

|

|

The chemical shifts obtained experimentally do indeed support the structural assignment in literature. There were however some discrepancies, one of the reasons for which may be the rotation of the phenyl ring. This is supported by the fact that the greatest deviations from literature are with the phenyl carbons. Since the chemical shifts for the carbons in both isomers are in very similar environments, using 13C NMR is not a very useful tool in distinguishing between the two when no literature values are at hand. A more useful method is to analyse the 1H NMR; unfortunately this NMR cannot be obtained accurately using the methods at hand. Luckily, we are able to obtain 3J(H-H) values - these are sufficient enough for the endo/exo isomerism case.

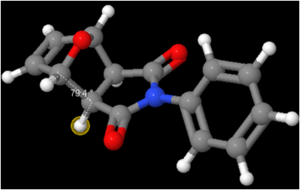

Cooley and Williams were able to differentiate between the two isomers by investigating the coupling constants of the 1H NMR. The difference in the splitting pattern observed in the NMR between the two isomers is due to the very different dihedral angles between the endo and exo protons and the protons on the bridgehead carbon atom (i.e between Ha-C-C-Hb), as shown below:

In order to determine the value of the required coupling constants, a 3D model of the isomers was opened in ChemBio3D (using the output file which emerged from the 13C NMR prediction). Having saved the models as an MDL Molfile, the file was then read into Janocchio to obtain predictions for the three bond coupling constants. This method is based on the Karplus equation: JHH(φ) = 8 cos2φ - 0.5 cosφ - 0.028.[16] The results are shown below:

| Isomer | Calc. Dihedral Angle(deg) | Lit.[15] Dihedral Angle(deg) | Calc. Coupling Constant(Hz) | Lit.[15] Coupling Constant(Hz) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

79 | 83 | 0.69 | 0.05 | |

|

34 | 33.8 | 6.5 | 5.2 |

The values obtained are relatively well matched with the literature, thus supporting the structural assignments. As the C-H bonds forming the dihedral in the exo isomer are nearly orthogonal to each other, this would result in the peak appearing as a singlet in the experimental NMR spectrum (which is observed in literature). On the other hand, the endo isomer would show coupling and the peak would split. The literature paper states that this reaction conforms to the ‘endo rule’ whereby the kinetically favoured product predominates over the thermodynamic one. Having deduced what the different splitting and coupling constants are for each isomer, one could then look at the NMR and instantly determine which isomer is the major product. Under equilibrium conditions, Mosey et al[16] showed that the final spectrum contained a singlet - this proves and reiterates that the thermodynamic product is the exo isomer. Overall, this computational technique has successfully allowed us to differentiate between the isomeric products and the findings are consistent with that found by Cooley and Williams.

The focus will now turn to the IR vibrational frequencies which were calculated as mentioned above.

| Functional group | Calculated Frequency[19] (cm-1) | Literature Frequency[20] (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| C-N | 1385 | 1380 |

| C=C | 1498 | 1496 |

| C=O | 1658, 1803 | 1715,1775 |

| C-H | 3114 | 3064 |

| Functional group | Calculated Frequency[21] (cm-1) | Literature Frequency (cm-1) |

|---|---|---|

| C=O | 1658, 1802 | 1713, 1696 |

|

|

Although some of the IR values differ between the calculated and experimental, both are within the correct frequency range for the corresponding vibration, for e.g the range for a C=O stretch is approximately between 1660 and 1800cm-1. Although not as useful as the coupling constants, this technique has still proved of some use. However, using the IR values on their own would not be enough to distinguish between the two isomers as the values are very similar to one another – this is unsurprising in endo/exo isomerism. It should also be noted that the Cooley and Williams article only had values for the carbonyl peaks, another journal was found for the exo adduct but not for the endo. To sum up, although IR successfully identifies the functional groups present in the molecules, it is not adequate enough to distinguish between the isomers in the reaction considered. It should also be pointed out that the computational method predicts the IR values in the gas phase, whereas experimental data are obtained from running the spectra at an ambient state. Other reasons why the values differed to the literature value may be due to the different positions of the phenyl group relative to the ring as well as other limitations in the computational techniques used.

Other spectroscopy techniques to distinguish between the isomers

As well as the techniques outlined above, NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser effect Spectroscopy) could also be useful in distinguishing between the two isomers. This technique allows one to measure the distance between two hydrogens. As shown above in the discussion of dihedral angles, the endo and exo form have different hydrogen orientations and thus NOESY would be effective in differentiating between such isomerism. X-Ray diffraction could also be used to differentiate as this technique analyses distances and angles between atoms, and for the same reason as above, it could be used to assign the nature of the isomers.

Possible Improvements

One of the issues commonly addressed in computational chemistry is the choice of whether the molecule under investigations should be simplified by, for example, removing bulky substituents. Although such simplifications will no doubt introduce errors (as it disregard any steric/electronic effects exerted by the substituent), but by doing so it allows the use of a more theoretical method.[16] In the case of the reaction considered here, the phenyl ring could be removed. To determine whether this simplified model would be valid for further calculations, the energies for the full and simplified systems should be compared and the relative energies of the exo and endo isomer. If the results are similar, then this model could then be taken forward.[16]

Conclusion

The computational methods used, specifically determination of the J coupling values, successfully distinguished between the endo and exo products of the Diels Alder reaction.

References

- ↑ The conservation of orbital symmetry. R. Hoffmann, R. B. Woodward, Acc. Chem. Res. , 1968 , 1 , 17 - 22: DOI:10.1021/ar50001a003 .

- ↑ Sauer. J, Sustmann. R, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. , 1980 , 19 , 779 - 807: DOI:10.1002/anie.198007791 .

- ↑ J.J. Zou, X. Zhang, J. Kong, L. Wang, Fuel, 2008, 87, 3655: DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2008.07.006

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 S. Leleu, C. Papamicaël, F. Marsais, G. Dupas, V. Leavacher, Tetrahedron: Asymmetry, 2004, 15, 3919: DOI:10.1016/j.tetasy.2004.11.004

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, pp. 319: DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ Paclitaxel (Taxol) Investigations Workshop Semin. Oncol. 20 (4, Suppl. 3), 1993, 1−60

- ↑ G. Bringmann, A.J.P. Mortimer, P.A. Keller, M.J. Gresser, J. Garner, M. Breuning, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2005, 44, 5384: DOI:10.1002/anie.200462661

- ↑ S. W. Elmore and L. Paquette, Tetrahedron Letters, 1991, 319: DOI:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92617-0

- ↑ W.F. Maier, P.v.R. Schleyer, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1981, 103, 1891: DOI:10.1021/ja00398a003

- ↑ B. Halton, S.G.G. Russell, J. Org. Chem., 1991, 56, 5553: DOI:10.1021/jo00019a015

- ↑ B. Halton, R. Boese, H.S. Rzepa., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 2, 1992, 447. DOI:10.1039/P29920000447

- ↑ Dig. Resp. IR prediction for Molecule 12.[1]

- ↑ Dig. Resp. IR prediction for Molecule 12 Hydrogenated.[2]

- ↑ Silverstein, R.M.; Bassler, G.C.; and Morrill, T.C. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. 4th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1981

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Cooley, J.H., Williams, R. V., J. Chem. Educ., 1997, 74, 582-585: DOI:10.1021/ed074p582

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Mosey, N.J., Rowley, C. N., Woo, T.K, J. Chem. Educ., 2009, 86, 199-201: DOI:10.1021/ed086p199

- ↑ Dig. Resp. NMR prediction for Exo Isomer.[3]

- ↑ Dig. Resp. NMR prediction for Endo Isomer.[ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7419]

- ↑ Dig. Resp. IR prediction for Exo Isomer.[ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7422]

- ↑ Vargas, J., Tlenkopatchev, M. A., Amer. Chem. Soc.,2003, 36,8483-8486

- ↑ Dig. Resp. IR prediction for Endo Isomer.[ http://hdl.handle.net/10042/to-7423]